What is culture? Simply speaking, it is the way of life for an entire society. Going wider and broader (like how I envision this post is going to be), it encompasses a whole plethora of domain – codes of manners, dress, language, religion, rituals, art, law and morality, and systems of belief. Indian culture is loud and proud and so evidently visible when you step across the threshold of your home. In contrast, there’s much curiosity surrounding the Korean culture. I am not talking about the apparent “green flag” guys depicted in K-dramas, or the BTS fandom. Beyond the on-screen va va voom, the word “Korea” paints of two active borders and missiles running across it. So, what happens when my proclivity runs a little more holistic and less exclusive? Well, why don’t I take you through the journey and see if we can come to a mutual agreement! 15 days was not enough to be honest, but I have tried to organize this travelogue in terms of historical moments and its correlating place. Let’s hope I am successful.

Pride of a Country – The Korean culture

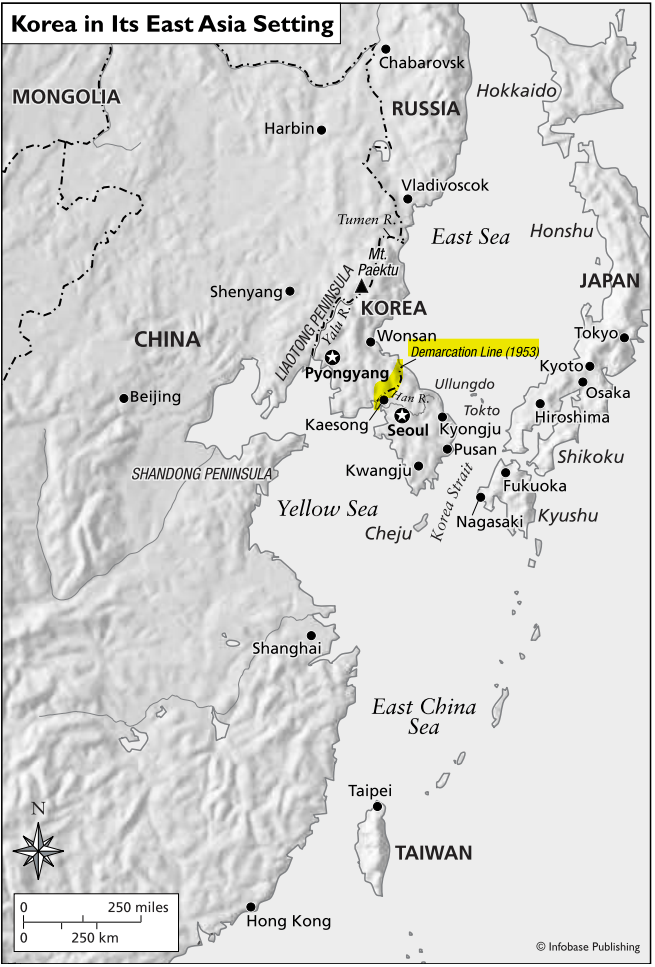

Stepping into South Korea in the chill of early November, and experiencing their unique K-culture, one thing was very evident: Koreans are immensely proud of their heritage and culture. The fact that Korea is one of the oldest countries in the world next to China, adds a significant part to their pride. Despite the unique global positioning of the peninsula, the origin of Koreans is not as clear cut and simplified as the boundary line suggests. The history, culture and philosophies of Korea can be best understood in terms of the way Koreans have interacted with their neighbors in the north (i.e. China, Manchuria and, more recently, Russia) and in the south and the east across the Korean Strait and the Sea of Japan (i.e. Japan and, more recently, the USA). And yet, every Korean identify themselves with a sense of jhung (~ kinship) to one of its founding myths of an early king, Tangun who was born when a bear prayed to become human, just by one line: “We, the descendants of Tangun . . .”

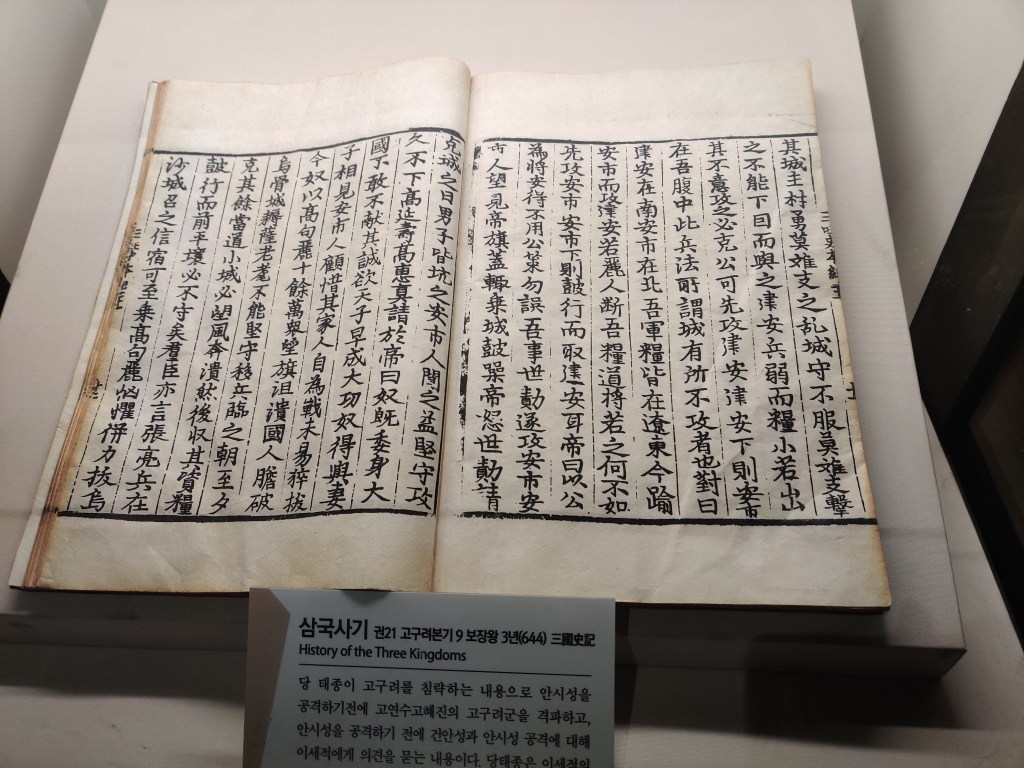

Regardless of its mythical status, Tangun is revered as the founder of Gojoseon, considered the first Korean kingdom, dating back to 2333 BC according to Chinese records like the Guanzi. Despite the indigenous nature of Korean myths, Chinese influence was pervasive on the Korean Peninsula, a common phenomenon in East Asia at the time. From 100 BC to AD 313, China exerted control over parts of the Korean Peninsula during the Han dynasty, impacting Korea’s political, economic, military, and religious spheres, as well as its writing system and technology. This influence extended to the adoption of Buddhism, Confucianism, and Taoism in Korea.

Following the fall of Gojoseon, the Proto-Three Kingdoms period emerged, marked by the rise of states like Goguryeo, Silla, and Baekje. This period, also known as the Several States Period, witnessed the formation of numerous states from the remnants of Gojoseon, including Eastern Buyeo and Northern Buyeo, shaping Korea’s early history.

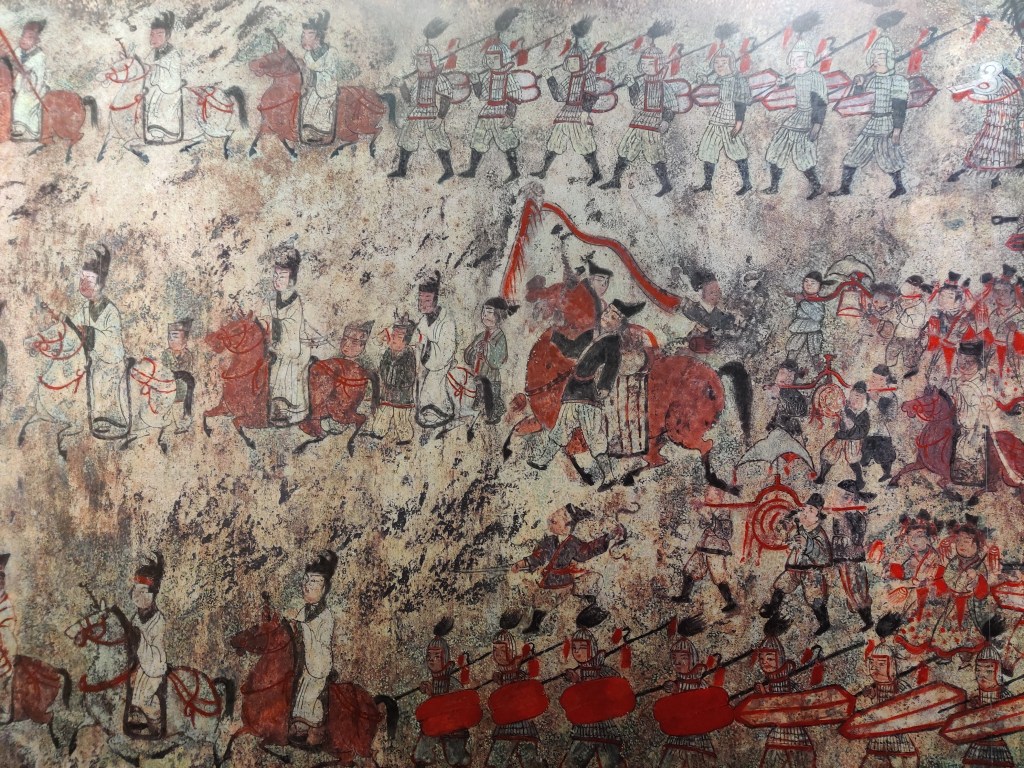

In ancient Korean history, the Three Kingdoms Period stands out prominently. It’s quite a spectacle to imagine three swords sharing the same scabbard, yet history paints a vivid picture. Spanning from the 4th century to 668, this era was marked by constant warfare. Each of the three kingdoms—Goguryeo, Baekje, and Silla—held power at different times, forming and breaking alliances with one another. Amidst this turmoil, Buddhism, with its emphasis on the value of life and death beyond national boundaries, flourished remarkably.

Contrary to its name, the period originally consisted of four kingdoms: Goguryeo, Baekje, Silla, and Gaya. While Goguryeo, Baekje, and Silla thrived into the 7th century, Gaya, subdued by Silla in the mid-sixth century, is often overlooked despite its significant role in Korea’s formation. Goguryeo (also spelled as Koguryŏ), a formidable militaristic state, controlled vast territories and fiercely contested the Korean Peninsula, shaping the region’s modern name. Under the rule of Yeongnak Taewang- Gwanggaeto (“Supreme King” or “Emperor” Yeongnak), Goguryeo rivaled imperial Chinese dynasties, notably defeating the Sui dynasty in the Goguryeo–Sui War.

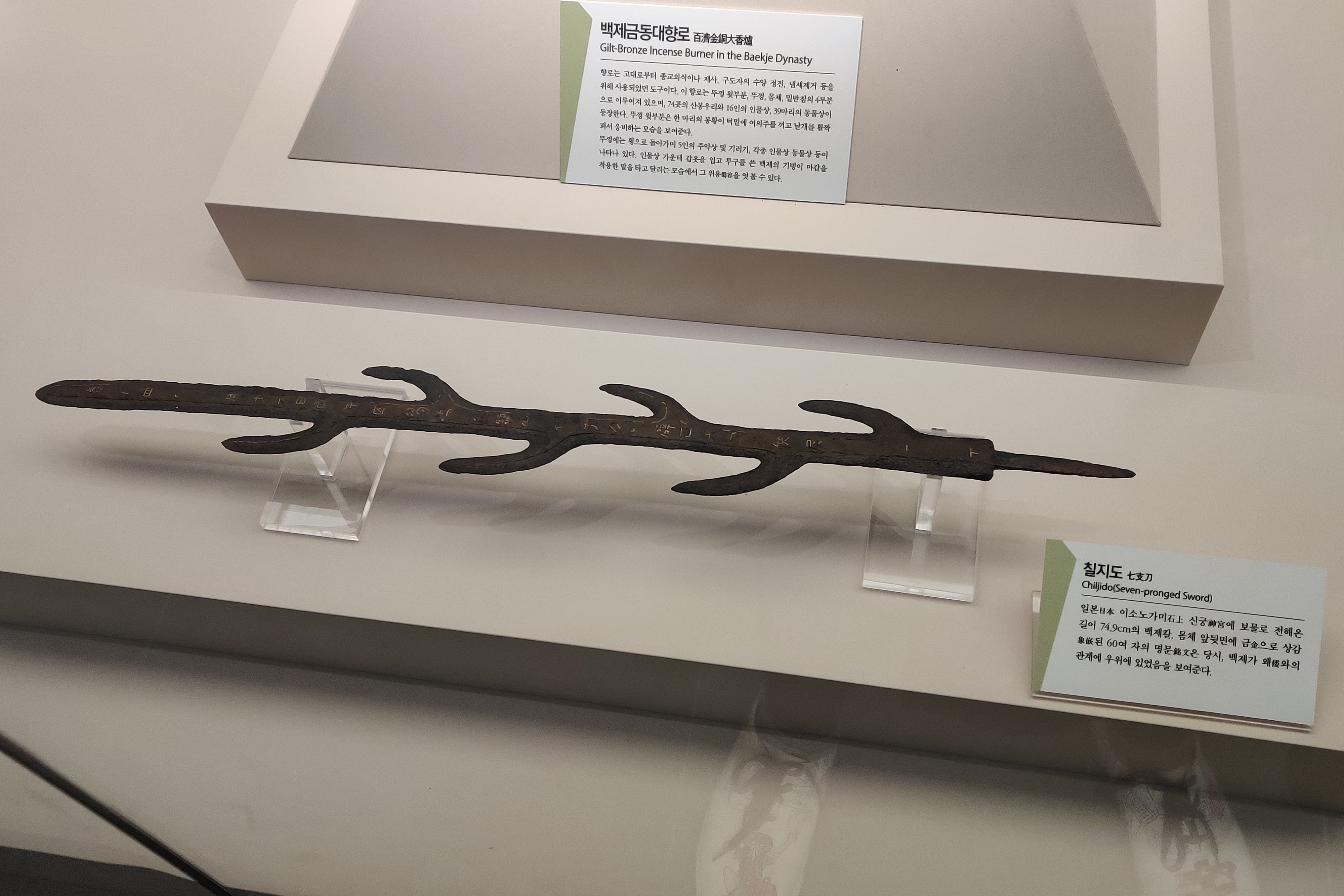

Baekje shares Goguryeo’s founding myth, originating from a Goguryeo prince. Unlike its counterpart, Baekje emerged as a dominant maritime power, earning the title of the “Phoenicia of East Asia.” Its maritime expertise facilitated the spread of Buddhism, Chinese characters, iron-making techniques exemplified by the Gilt-bronze incense burner, advanced pottery, and ceremonial burial practices across East Asia.

In contrast, Silla’s rise to power was propelled not only by its naval dominance, bolstered by control over the port city of Busan but also by strategic alliances and calculated agreements. With backing from China’s Tang dynasty, Silla conquered Baekje in 660 AD and Goguryeo in 668 AD. This conquest, albeit opportunistic, led to the unification of the Korean Peninsula in the 7th century, fostering Korea’s first unified national identity.

Interestingly, China’s Han dynasty influenced Korean politics before Korea’s own reunification. The Silla-Tang War of 676 AD marked the inception of Unified Silla’s golden age. This period saw the adoption of Chinese governance structures, an expanded role for the king and central government, and the rise of a prosperous aristocracy. Buddhism flourished, exemplified by landmarks like the Bulguksa Temple, reflecting a rich cultural legacy that endures in Gyeongju, the former capital of Unified Silla. Gyeongju served as a pivotal trade hub between China and Japan, earning praise from foreigners like the Persians as seen from an anecdote: “In this beautiful country Silla, there is much gold, majestetic cities and hardworking people. Their culture is comparable with Persia.“

Spanning from the Three Kingdoms period to Unified Silla, Tumuli Park houses over 300 tombs, chronicling nearly a millennium of Silla culture. These immense earthen mounds, some towering up to 50 feet, served as the final resting places for Silla’s monarchs and nobles. The presence of these tombs contributed to the designation of Gyeongju as a UNESCO World Heritage Site. Notable among these burial sites is the Geumgwanchong Tomb, unearthed in the 1970s and renowned for containing the sole surviving painting from the Silla era.

Adjacent to Tumuli Park lies Wolseong Park, home to the oldest surviving astronomical observatory in East Asia, the Cheomseongdae observatory. Dating back to the 7th century AD, this structure consists of 366 stones, symbolizing the days in a year, arranged in 27 layers in honor of the 27th ruler, Queen Seondeok. Additionally, the observatory features 12 base stones representing the months. Beyond its historical significance, Wolseong Park is also famous for its Pinky Muhly fields, adding a touch of natural beauty to the area.

Unified Silla reigned for 267 years until King Gyeongsun surrendered the kingdom to Goryeo in 935 AD, concluding a rule spanning 992 years and 56 monarchs. The Gyeongju National Museum stands as a testament to this rich history, housing a collection of over 80,000 relics, though only 2,500 are displayed at a time. Among its treasures, the museum boasts the renowned Emille Bell, also known as the Divine Bell of King Seongdeok. Cast in 711 AD, this bell weighs an impressive 18.9 tons, making it the largest bell in Asia. Unlike Western bells, it is rung from the outside by a wooden battering ram rather than a clapper inside. Legend has it that when the bell was first cast, it remained silent until a child was thrown into the molten pit. The resulting sound, “Emi, emi, emi, emile” (meaning “Mommy, mommy, mommy, for your sake“), gave rise to its evocative name and mythical tale.

It’s often tempting to overlook historical details, especially when the strength of a kingdom fades from the annals of major historical events. Balhae, known as the Prosperous Country in the East, was a prime example. Founded just three decades after the fall of Goguryeo, Balhae embraced the cultural and political influence of the Tang dynasty. Despite its relative weakness, Balhae fell to the Khitan-led Liao dynasty in 926. Many refugees, including Dae Gwang-hyeon, Balhae’s final crown prince, sought refuge in the Goryeo kingdom. The ravages of war erased much of Balhae’s historical records, a loss compounded by Goryeo’s lack of documentation about its absorbed territories. It was Joseon dynasty historian Yu Deuk-gong who championed the study of Balhae as part of Korean history, coining the term “North and South States Period” to describe this era.

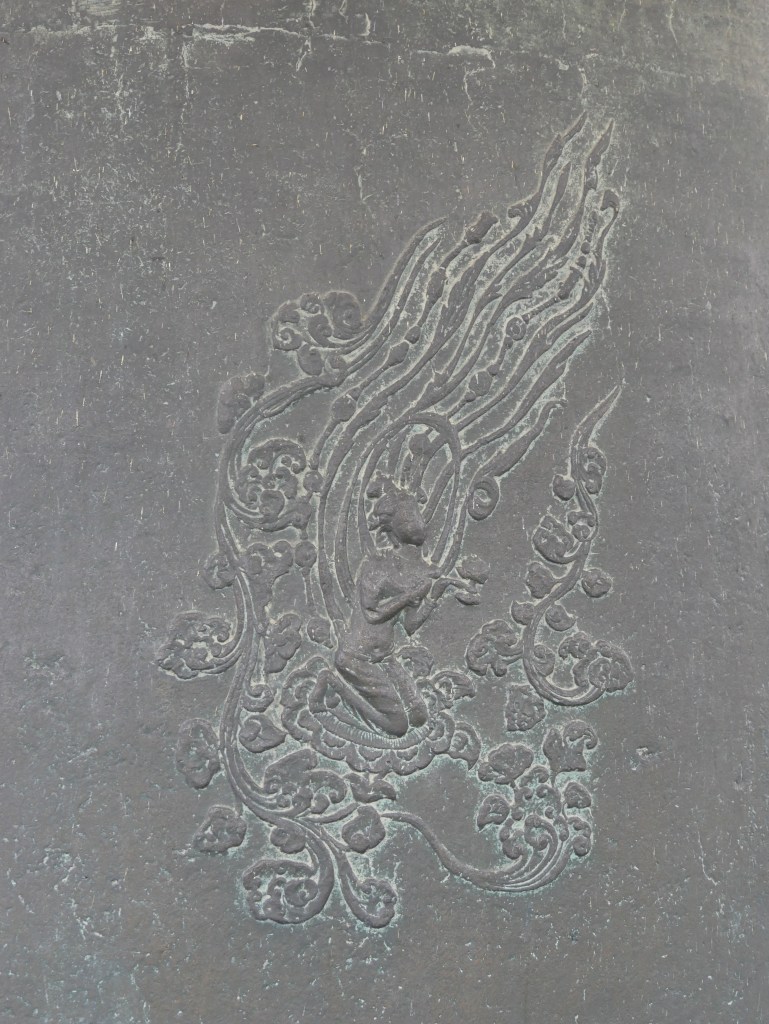

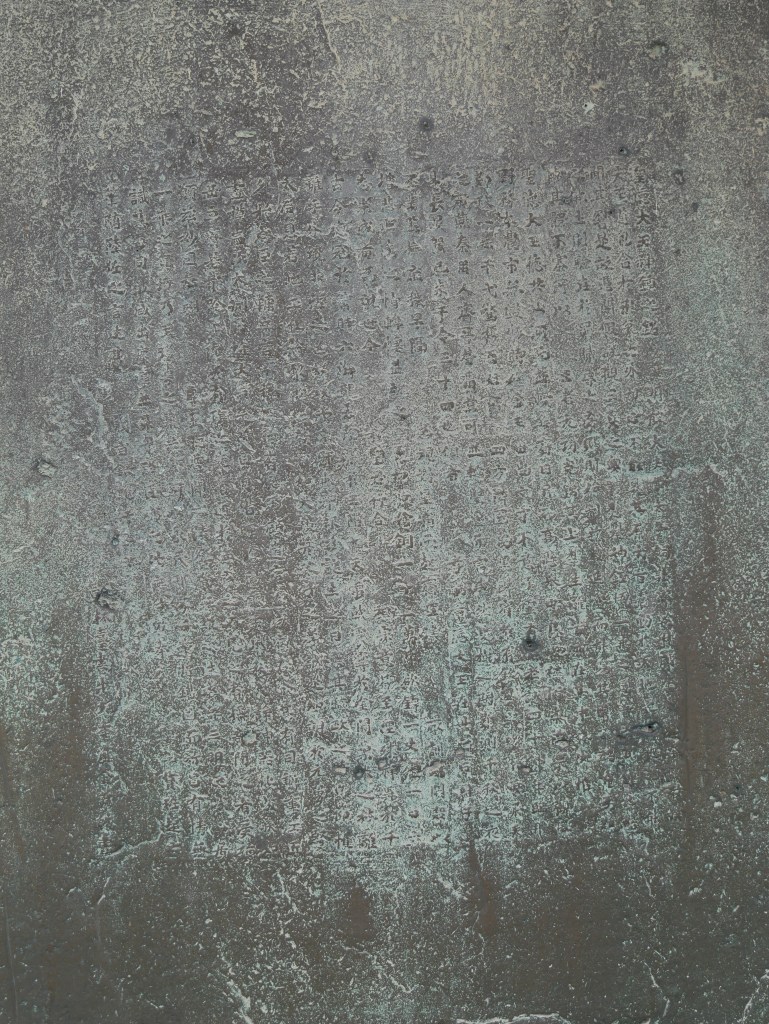

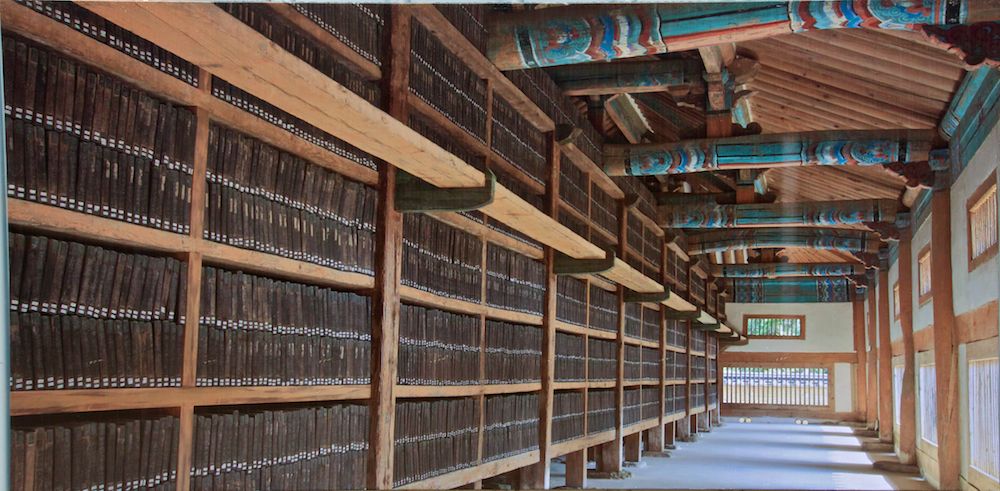

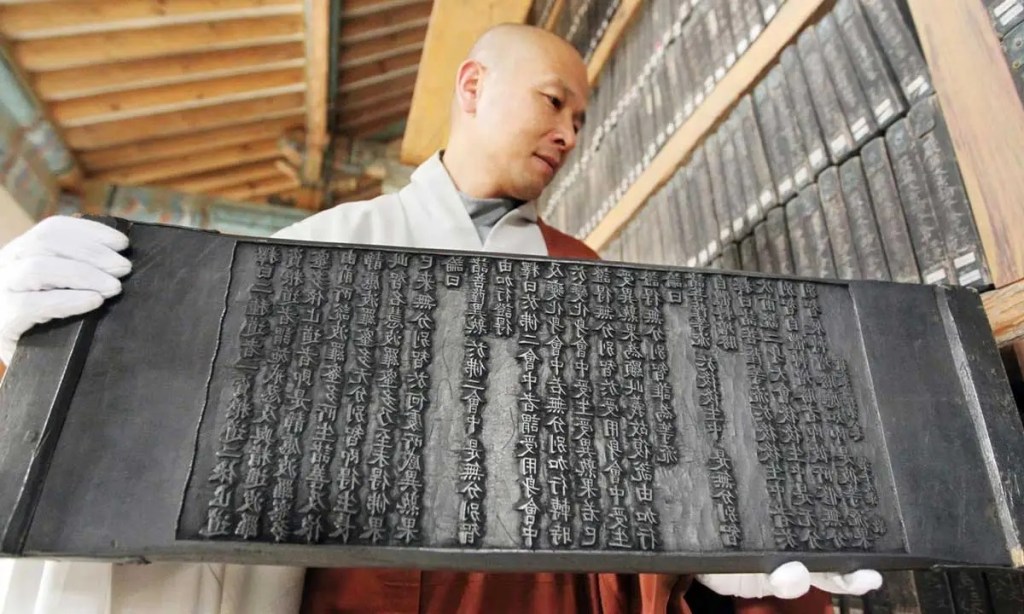

The Goryeo dynasty, established by Wang Geon in 918, rose to power in Korea by 936, seen as the successor to the former Goguryeo dynasty. Lasting nearly 500 years, from 918 to 1392, the Goryeo (also spelled as Koryŏ) reign experienced both periods of peace and turbulent years of war. Notable conflicts during the Koryŏ period include the Goryeo-Sui confrontations and the Goryeo-Khitan war. Unlike previous rulers, Koryŏ is renowned for its cultural achievements rather than its military or political endeavors. Koryŏ contributed significantly to the development of the first civil system and laws, as well as the creation of Koryŏ celadon, a celebrated aspect of Korean culture. Additionally, the Koryŏ dynasty witnessed two groundbreaking advancements in printing: In the early 13th century, the Tripitaka Koreana, a collection of Buddhist scriptures, was meticulously carved onto 81,258 printing blocks, containing over 52 million characters from the Hanja script. This monumental work, housed at Haeinsa Temple, consists of 1,496 titles and 6,568 volumes. Remarkably, Korea also pioneered metal movable typography around the same time, nearly two centuries before Johannes Gutenberg introduced typography in Europe.

As fate would have it, politics proved to be a fickle companion for Korea when faced with its greatest test of independence: the Mongol invasion. In the early 13th century, Koryŏ initially aligned with the Mongols against the Khitan. Interestingly, during the Choe military regime in Korea, historical connections intertwined, altering the course of destiny. While the Choe rulers governed Japan for a brief period of four generations (62 years), the Japanese bakufu held power for over 700 years, a transition occurring within a decade of each other. This military rule prevailed in Japan from 1160, preceding Chong Chungbu’s takeover in Korea. Although Korea reverted to civilian governance in 1258 after 62 years, Japan remained under military control until the late 19th century.

The second historical tangent of the Choe military government leads to the Mongol invasions of 1231. These invasions initiated a tribute system that included a demand previously unmade by the Chinese: slaves. It’s estimated that the Mongols captured at least 200,000 slaves during their control of Korea from 1231 to 1368. Following the fall of the military regime, subsequent peace treaties mandated that each Korean king, for eight generations, send his crown prince to be raised in Beijing. Additionally, each king had a Mongol mother and wife, marking a significant Mongol influence in the Korean court. The Yuan dynasty of China referred to Korea as a “son-in-law kingdom,” as Korean kings married the emperor’s daughters, establishing familial ties. Conversely, Korea also served as the “mother” kingdom, providing the emperor’s mother.

Following the fall of the Yuan dynasty in China, Korea saw the rise of a new ruling dynasty in 1392 – The Chosun dynasty (also known as the Yi dynasty or the Joseon dynasty). It was established under the leadership of Koryŏ’s former General Yi Songgye, who later assumed the title King Taejo, a customary “temple name” following the Chinese tradition. King Taejo, in his endeavor to rewrite history, undertook various reforms, including the relocation of the kingdom’s capital to Hanyang, present-day Seoul, the capital of South Korea. This strategic move led to the construction of the Gyeongbokgung palace in 1395, serving as the central court.

Subsequent rulers, including King Taejong and King Sejong the Great, oversaw the continuous expansion of the palace. However, it suffered significant damage due to fire in 1553, prompting a costly restoration under King Myeongjong’s reign. Four decades later, during the Japanese invasions of Korea from 1592 to 1598, the entire Gyeongbokgung Palace was once again ravaged by fire. Gwanghwamun Gate, the main entrance to the palace, stands as the largest and most imposing of the four gates. Another popular spot for tourists, especially Instagrammers, is the Heungnyemun gate, where Gatekeepers stand on duty in two-hour shifts, adding to the historical ambiance of the site.

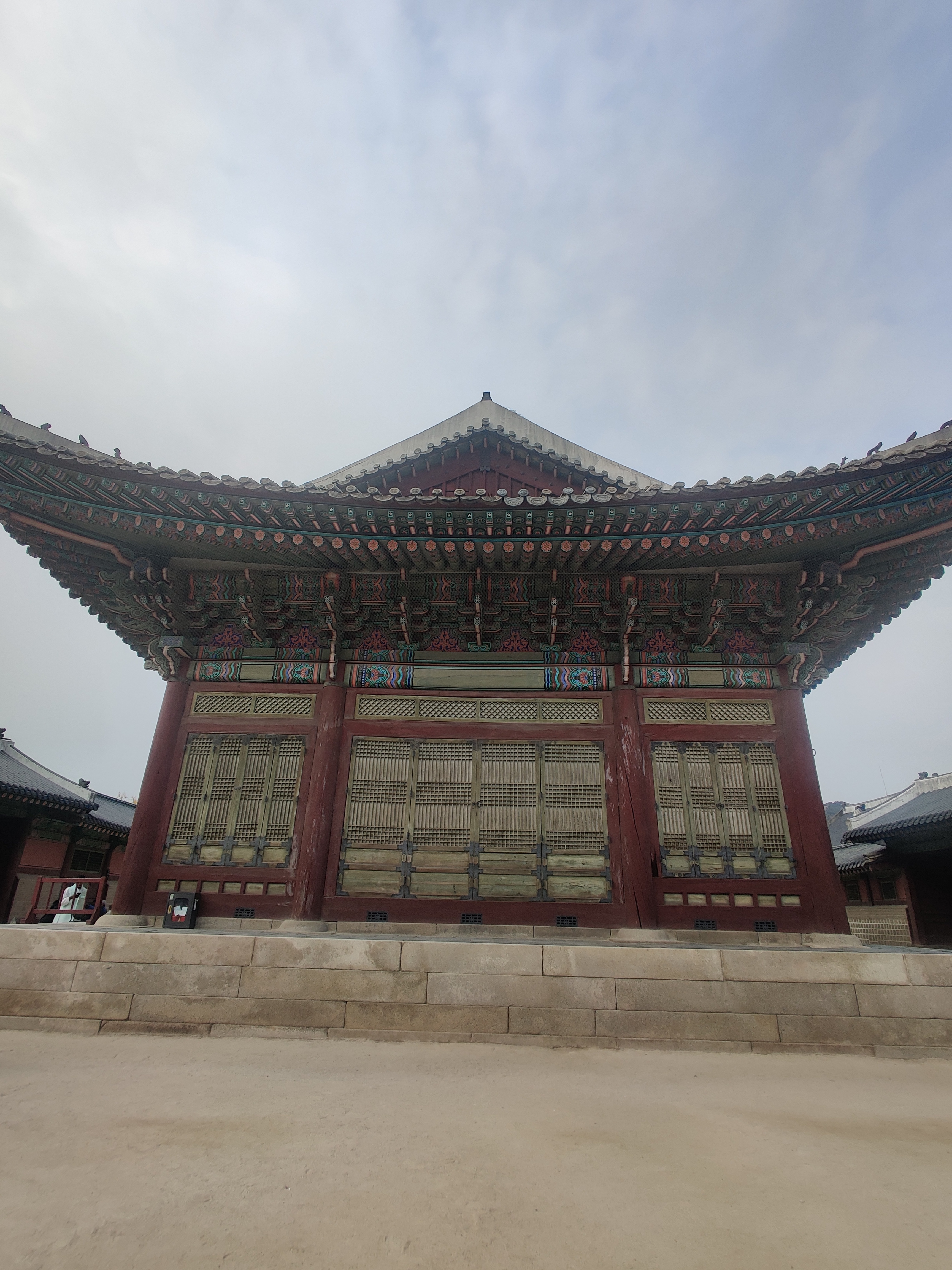

Geunjeongmun gate stands as the southern entrance to Geunjeongjeon, the main hall of Gyeongbokgung Palace. Flanked by corridors on both sides, the gate showcases the dapo architectural style, renowned during the Chosun (Joseon) dynasty. Divided into three separate aisles, only the king had the privilege to pass through the center aisle.

Directly beyond the gate lies the Geunjeongjeon Hall, also known as the throne hall, representing the largest and most ceremonious structure within the complex. This hall holds the distinction of being designated as Korea’s National Treasure since 1985. Historically, the name “Geunjeongjeon” was coined by Jeong Do-jeon, a minister and close advisor to King Taejo, meaning “diligent governance hall”. Adorning the canopy of this hall is a special screen adorned with auspicious imagery, including the sun, moon, five mountain peaks, and pine trees, symbolizing the absolute and eternal power of the Joseon King.

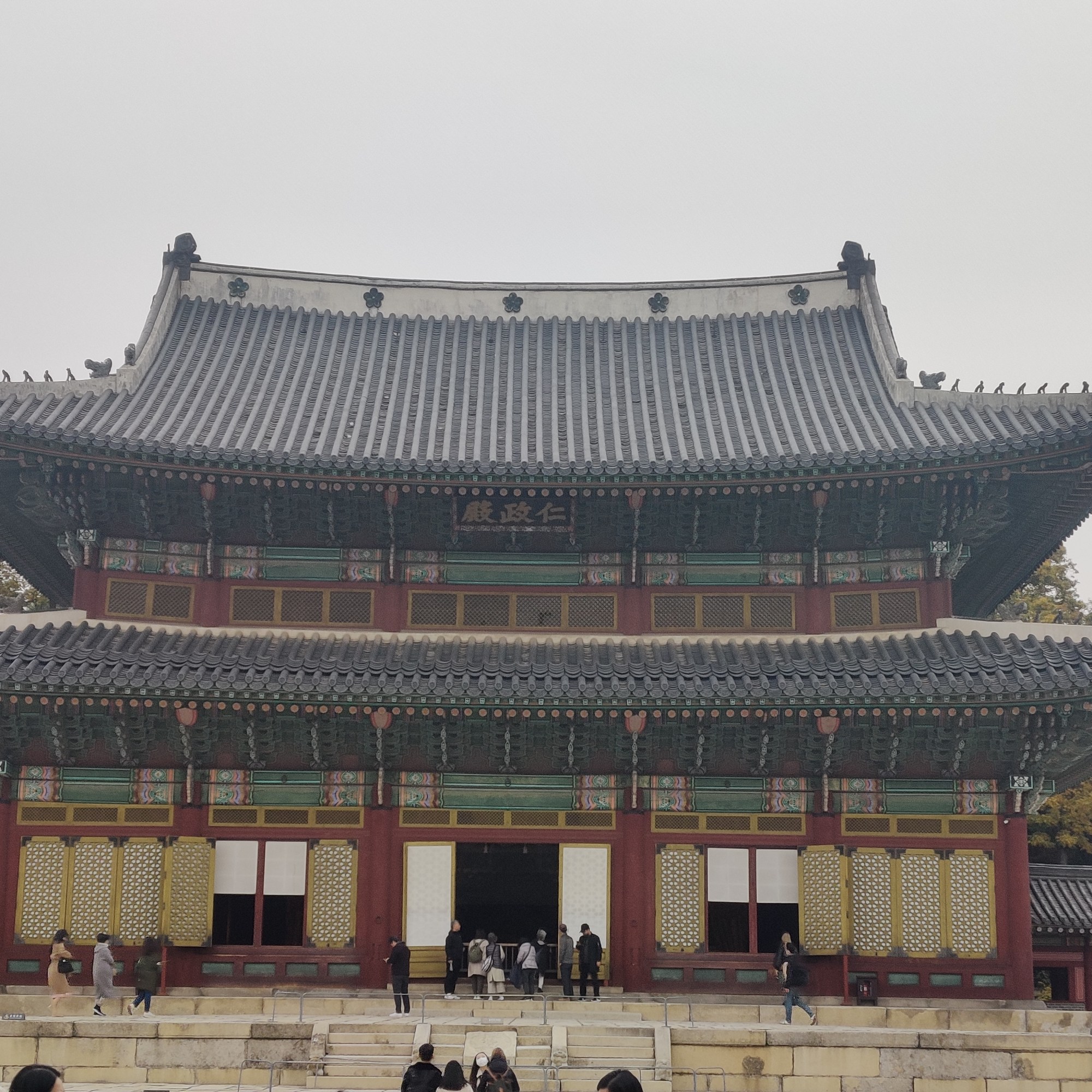

While Gyeongbokgung Palace often steals the spotlight for tourists exploring royal palaces in Korea, Changdeokgung Palace holds its own allure. Among the Five Grand Palaces constructed during the Joseon dynasty, Changdeokgung earned its place on the UNESCO World Heritage List in 1997 for its exceptional representation of Far Eastern palace architecture and garden design. The palace’s cameo in the immensely popular Korean drama “Dae Jang Geum” further enhances its appeal for K-drama enthusiasts.

Rooted in Confucian and pungsu principles guiding site selection and architectural styles, Changdeokgung Palace served as the royal court and governmental seat until 1868. Its construction in 1405, initiated during the reign of King Taejong amid a power struggle between brothers, concluded in 1412.

The dynasty faced challenges despite its establishment. King Taejo’s polygamous relationships resulted in a power struggle known as the Strife of Princes, leading to the reign of King Taejong. His rule, marked by ruthless tactics to secure power, laid the groundwork for the dynasty’s continuity, albeit at the cost of many rivals’ lives. Taejong’s reforms bolstered socioeconomic, political, and administrative structures, setting the stage for his successor, the revered King Sejong.

Sejong’s reign is legendary for his contributions to various fields. He spearheaded research in medicine, pharmacology, and agronomy tailored to Korea’s unique environment. His support for agricultural innovations, including the rain gauge, water clock, and sun dial, aimed to enhance the populace’s well-being. Sejong’s governance earned him the title “Ruler for the People,” reflecting his commitment to improving lives.

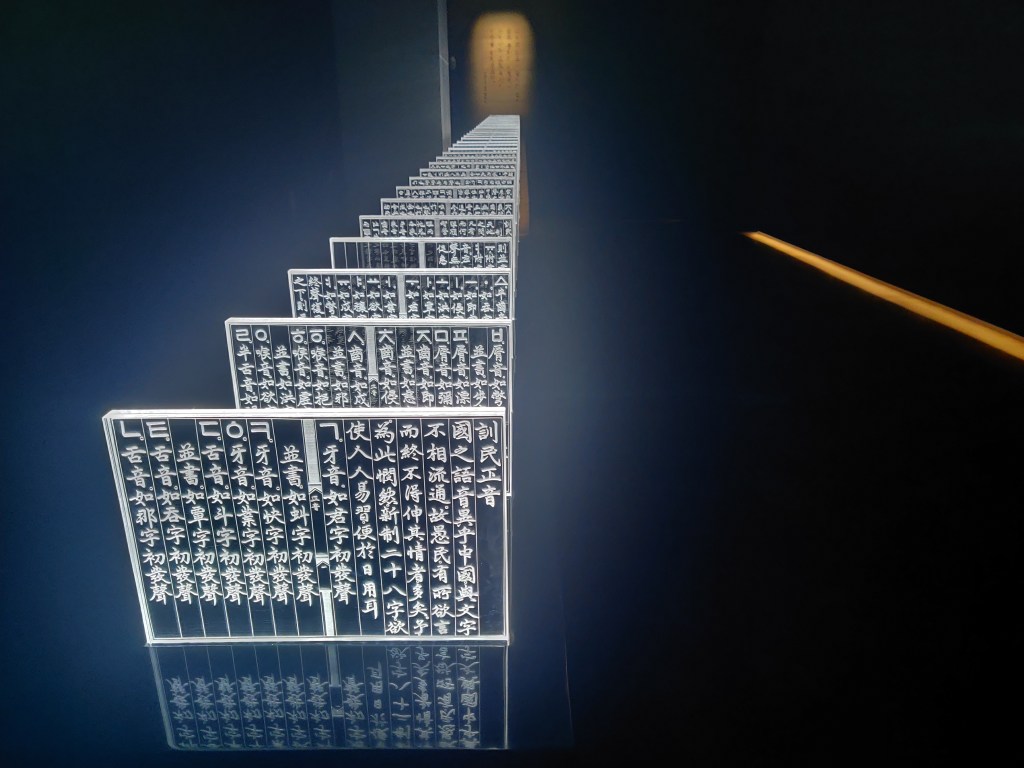

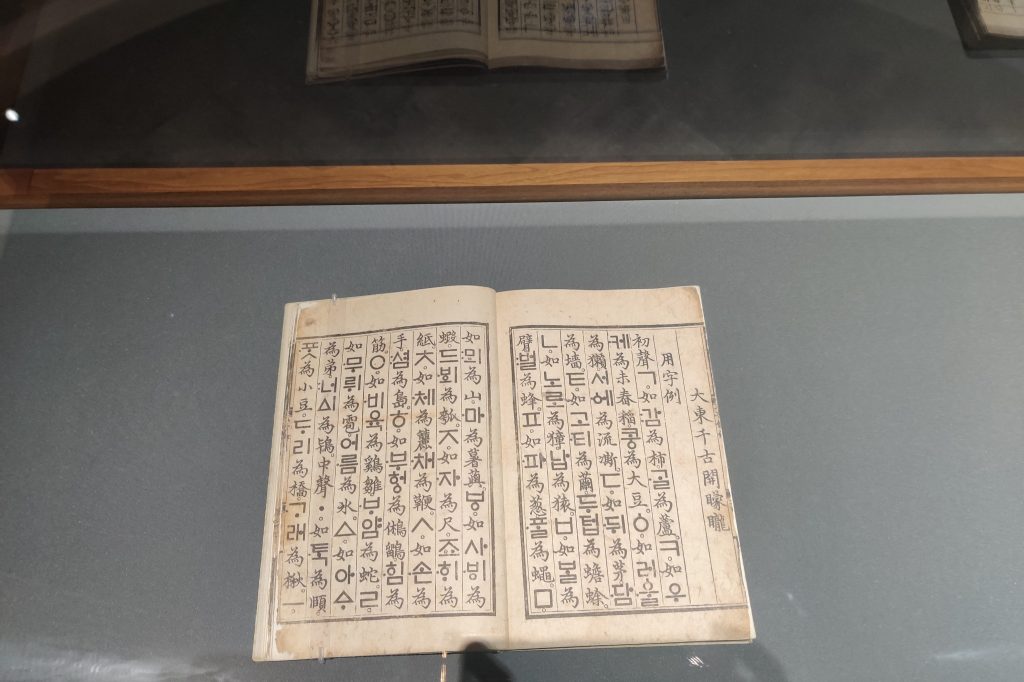

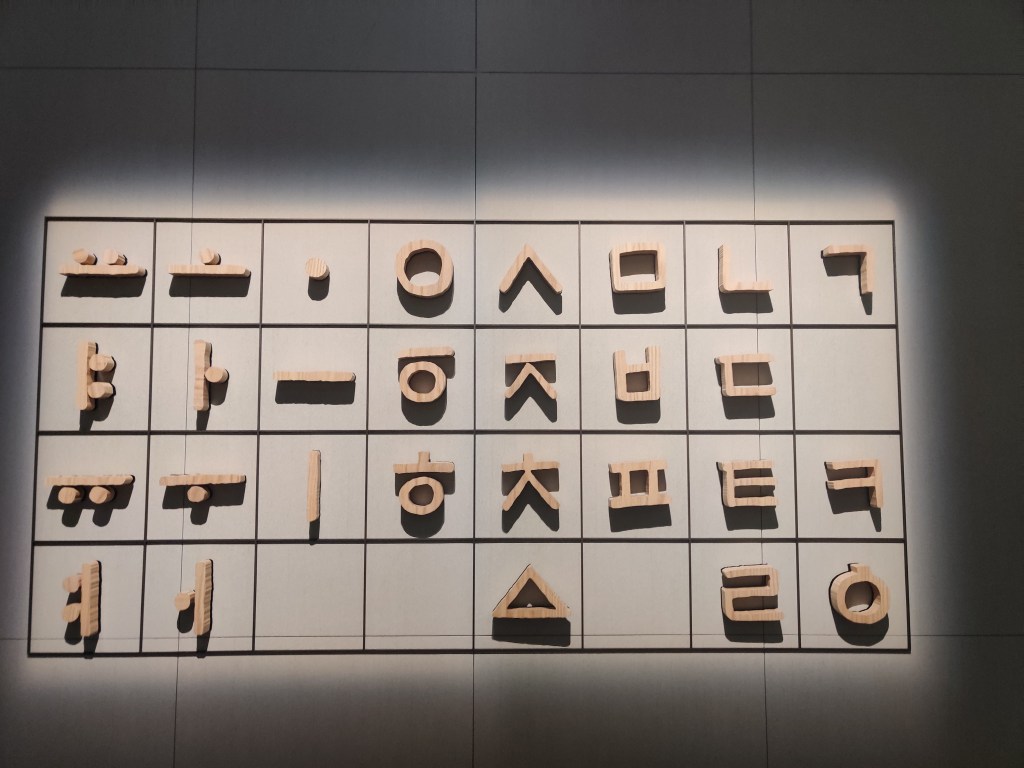

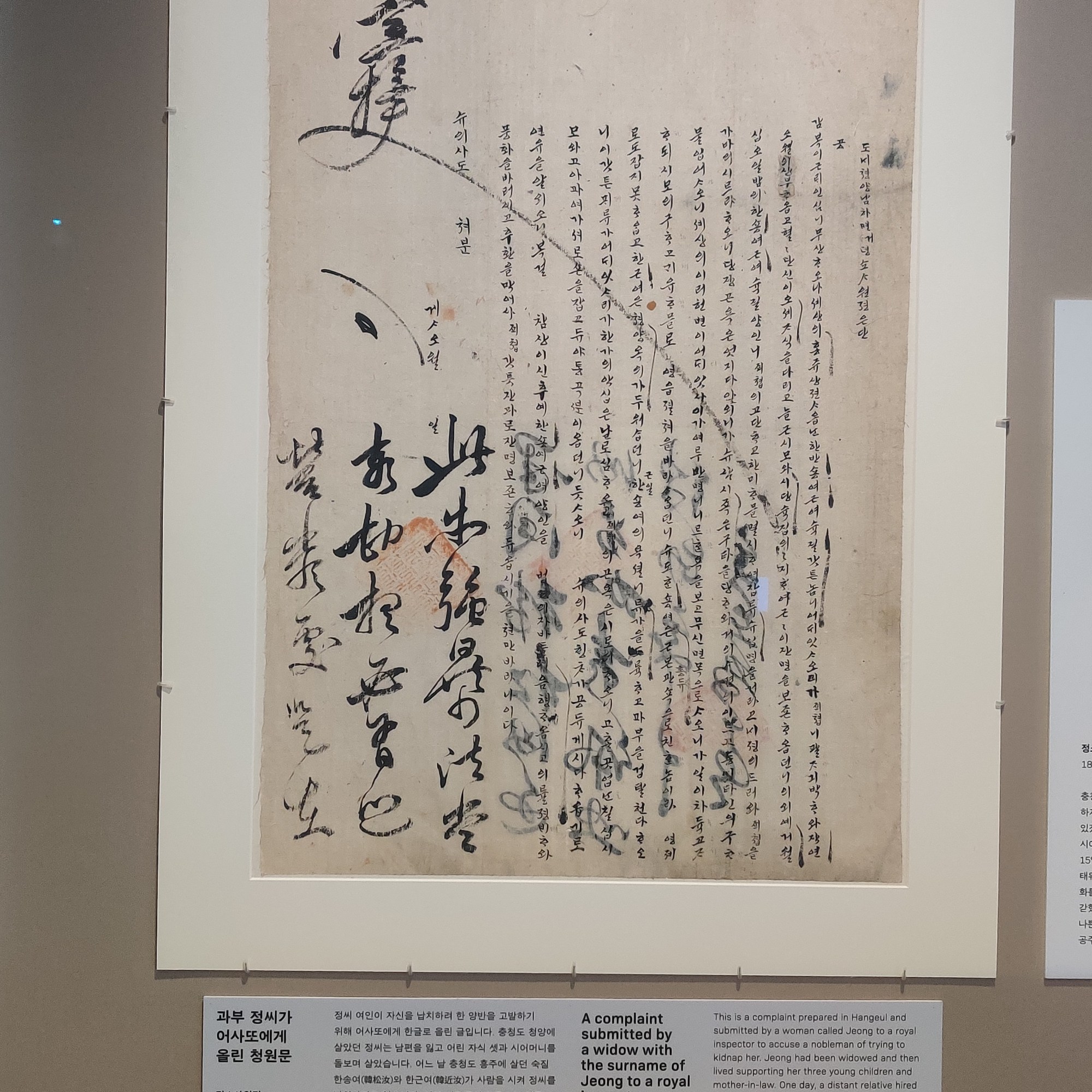

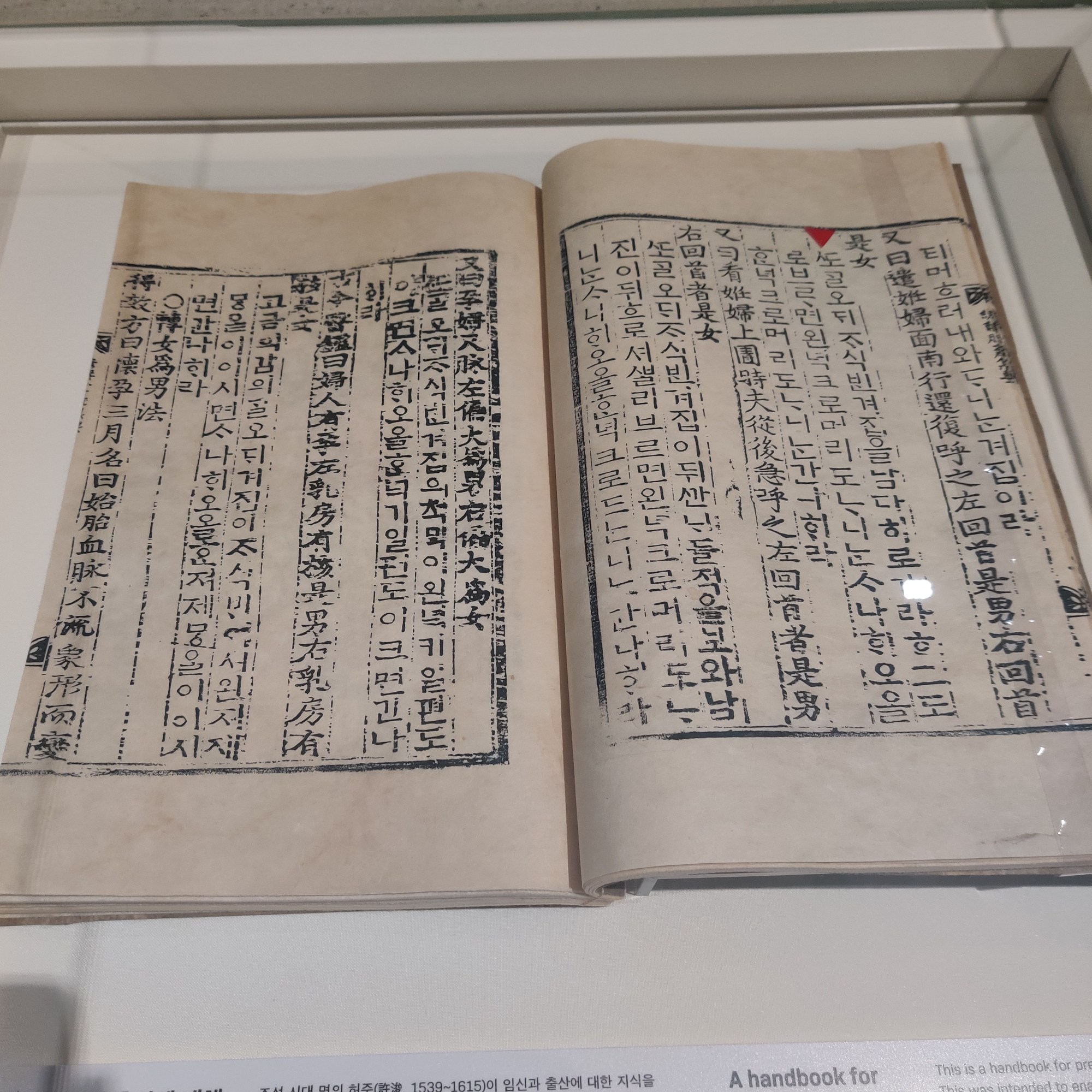

Among Sejong’s numerous achievements, none surpasses his creation of hangul, the Korean alphabet. Prior to its development, Korean writing heavily relied on Chinese characters, known as ‘Hanja’, due to centuries of close relations with China. However, this posed challenges as only the upper class, proficient in Chinese, had access to literacy. Various attempts were made to adapt Chinese characters, such as ‘Idu’, ‘Hyangchal’, and ‘Gugyeol’, but these methods were complex and limited literacy to the privileged few.

Recognizing the power of literacy in shaping society, King Sejong sought to democratize access to writing. Thus, he devised a simple and intuitive script, hangul, ensuring that literacy was no longer the exclusive domain of the elite.

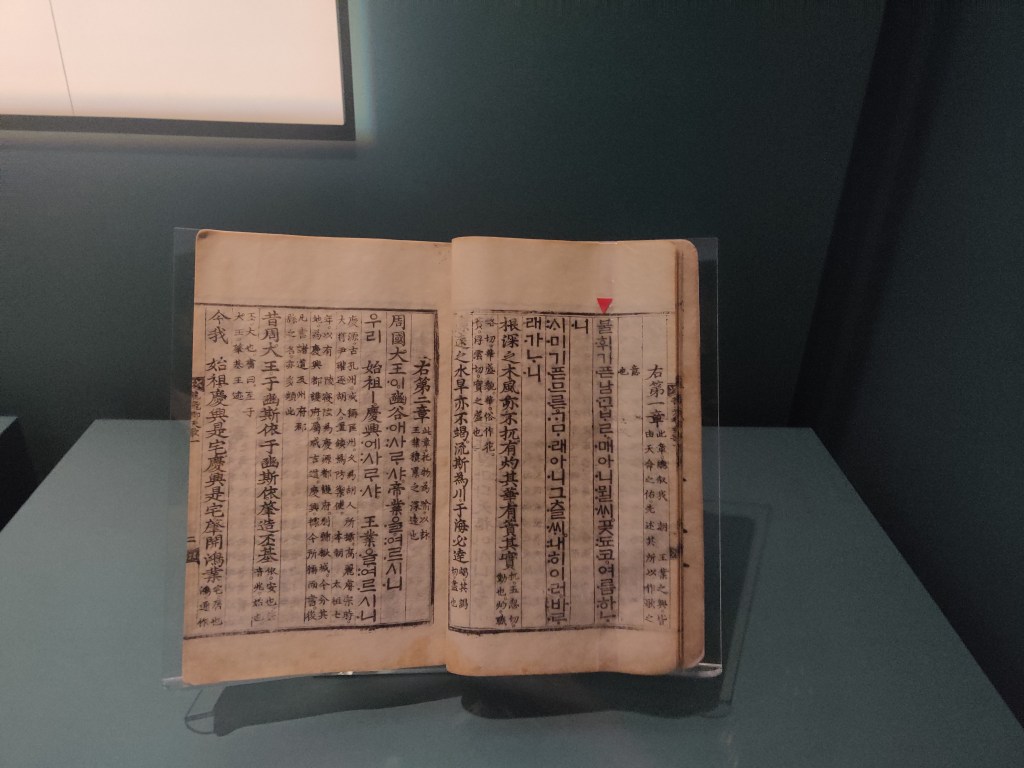

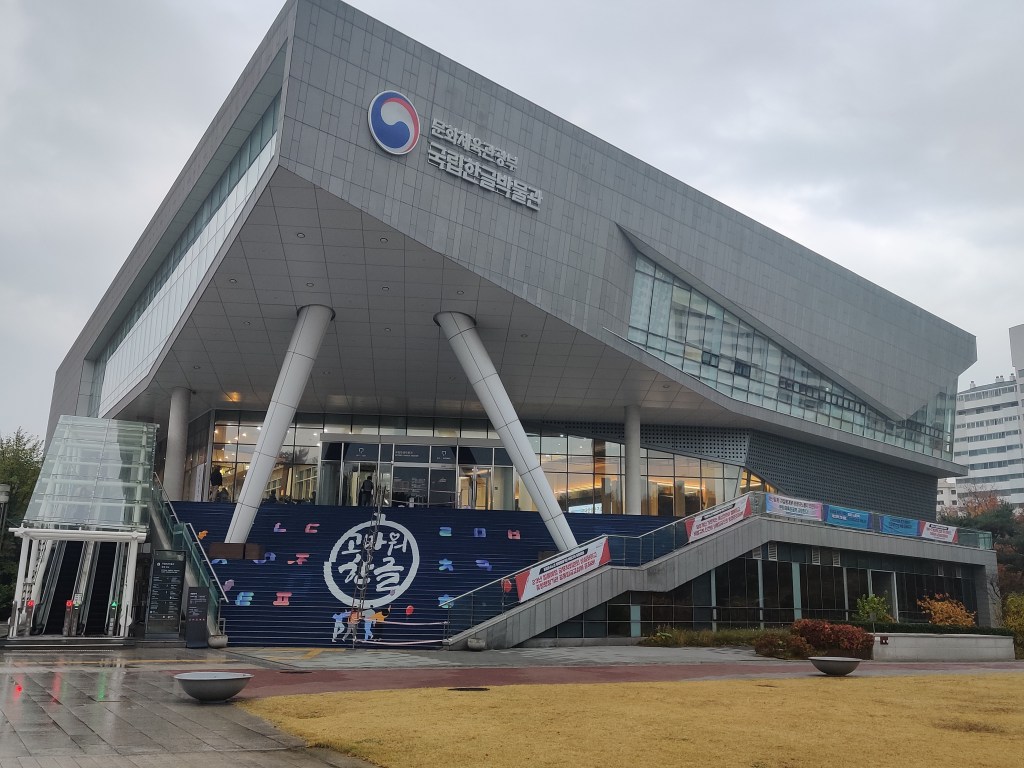

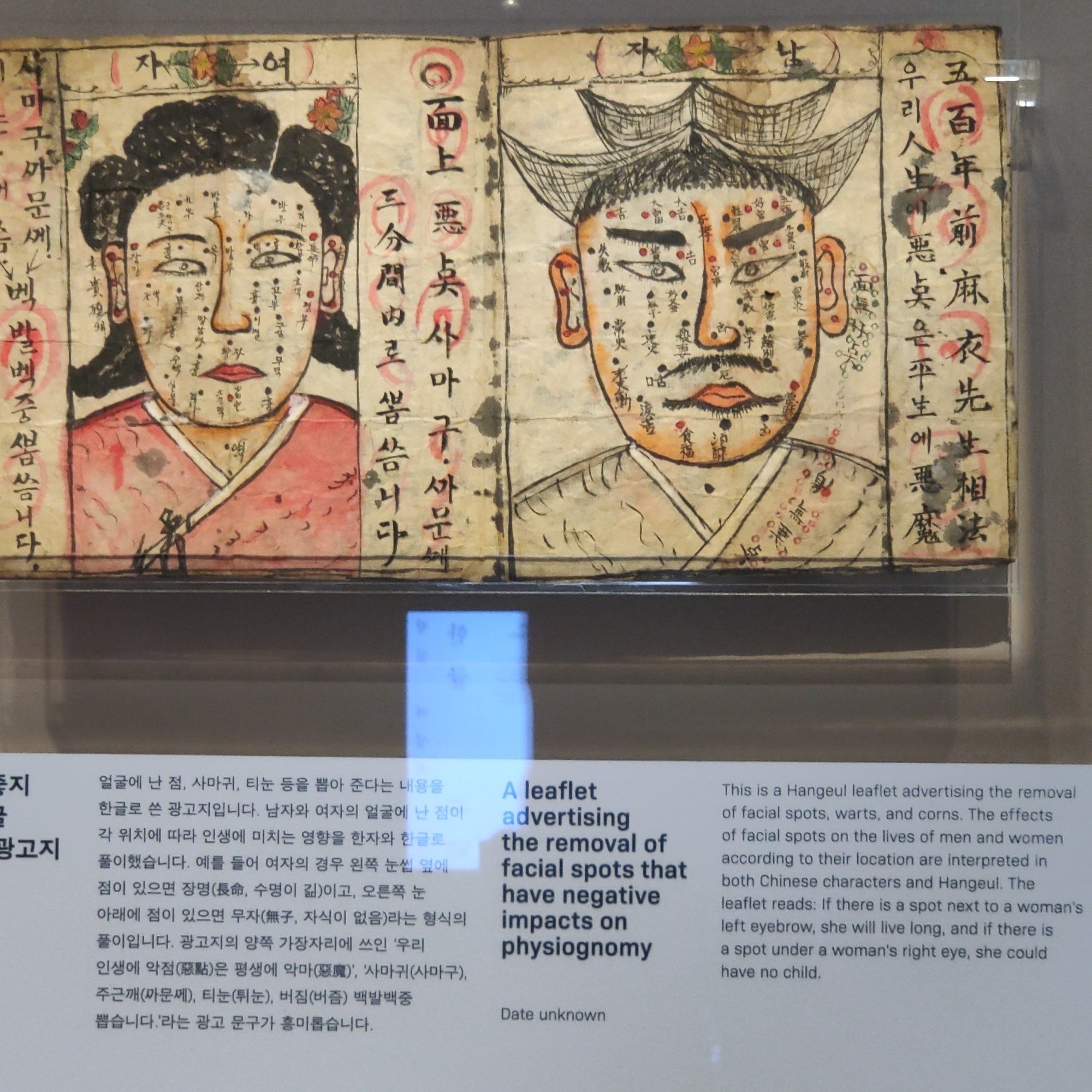

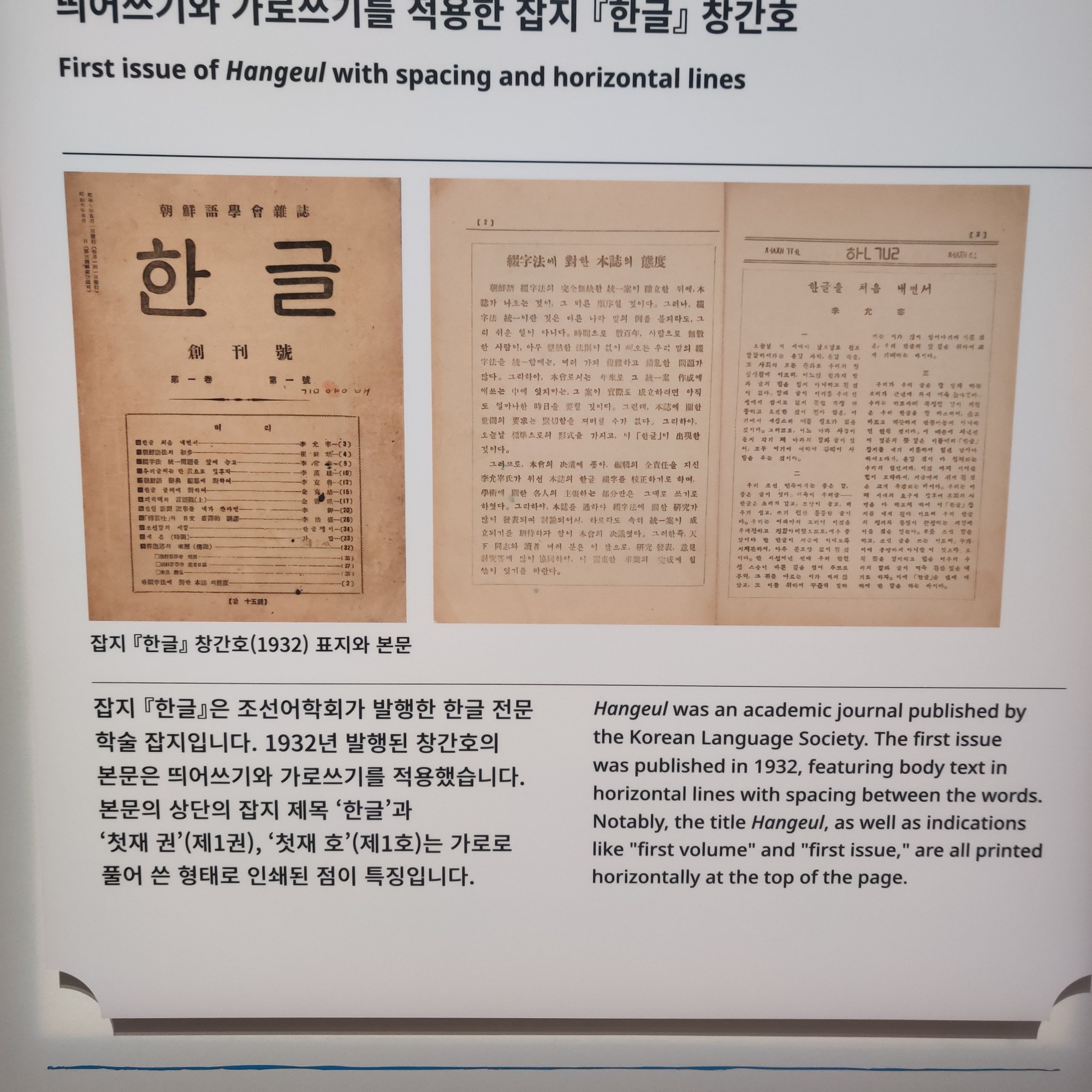

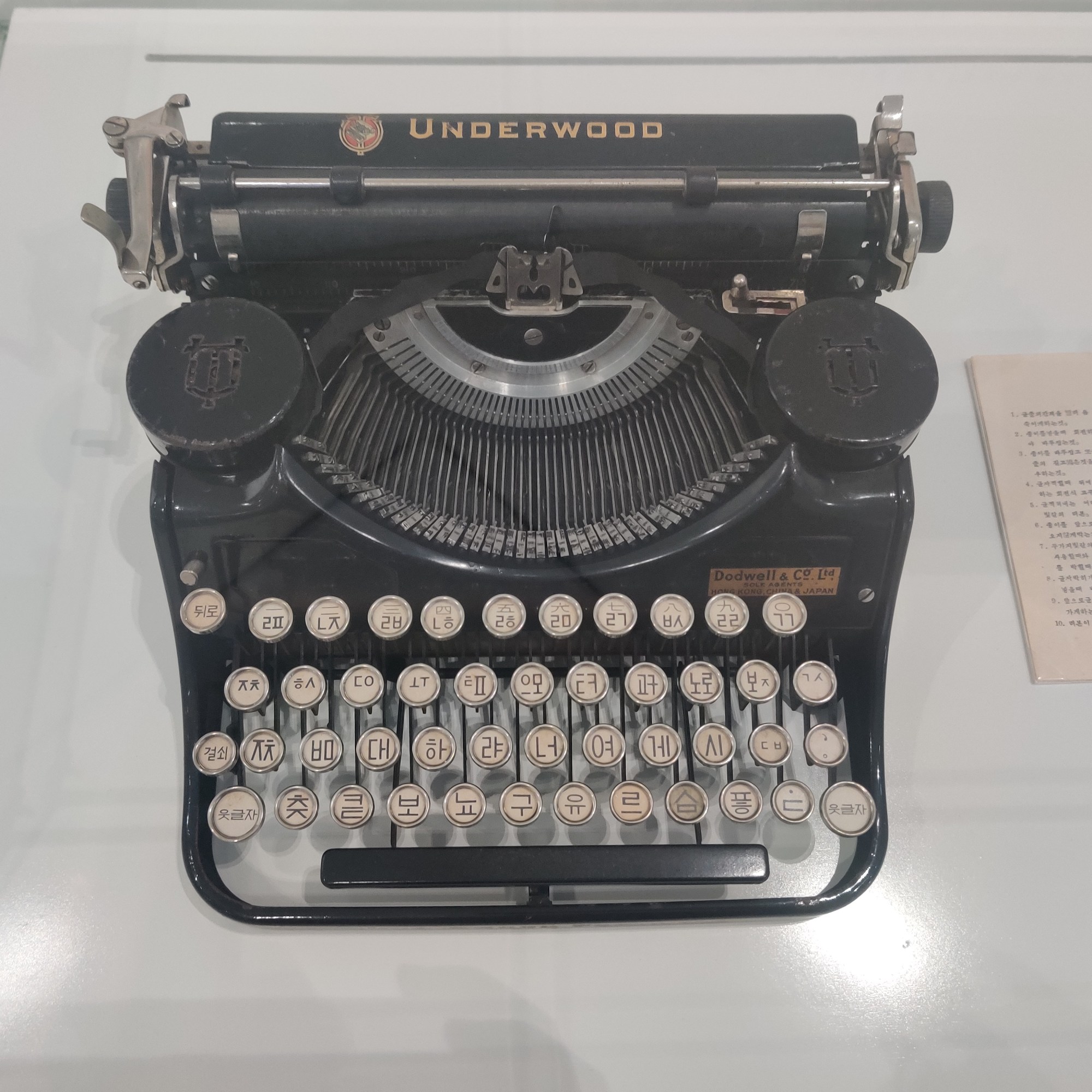

Hangeul is unique among alphabets for having its creation meticulously documented in a book called Hunminjeongeum. This historic document not only outlines the background and principles behind Hangeul’s creation but also details when, how, and by whom it was reinvented. King Sejong, in his quest to demonstrate the effectiveness of a common language, initially composed 125 poems in Hangeul. He then proceeded to refine the spelling rules to better capture the nuances of the Korean language and accurately convey the pronunciations of Chinese characters. Originally comprising 28 characters, today’s Hangeul consists of 24 characters (10 vowels and 14 consonants), with four letters falling into disuse over time. Thus, Hangeul remains a dynamic system, adapting to evolving linguistic needs in Korea. The National Hangeul Museum, probably my most favorite building ever, serves as a testament to its cultural, political, and linguistic significance, offering insights into its structure, evolution, and contextual relevance.

The essence of a nation’s pride often lies in the manifestation of its identity. Few things capture this essence as profoundly as the revitalization brought about by Hangeul in Korea. However, Hangeul faced its greatest threat during the reign of Sejong’s son, King Sejo. His ascent to power prompted criticisms written in Hangeul, leading Sejo to ban the alphabet and destroy existing printed materials. Subsequently, Hangeul was relegated to clandestine use for centuries, from the late 15th to the late 19th century.

If there are three things, that I would take back as a unique identifier of South Korea, it would be its 3Hs – Hanguel, Hanbok and Hanok. Nothing defines cultural identity of a country and its people more than how they speak, what they wear, and how they live. anok, dating back to Korea’s inception, embodies a lifestyle intertwined with social and political history, particularly flourishing during the Joseon period. Noteworthy is its construction, employing hand tools and eschewing nails. Confucian ideals further influenced the layout, emphasizing gender-segregated spaces. The Bukchon Hanok Village, comprising 900 traditional houses, offers a glimpse into Joseon’s elite society.

During the Middle Joseon period, religious ideologies often fueled conflicts. Buddhism and Confucianism, introduced to Korea around the same time (between the 4th and 6th centuries), held varying degrees of influence. Buddhism flourished during the Silla and much of the Koryo period (918-1392). For instance, the founder of the Koryo dynasty, for instance, formulated the Ten Injunctions, amalgamating elements of both Buddhism and Confucianism to guide his successors.

Confucianism, on the other hand, gained a greater momentum during the Koryo period and later became the dominant ideology of the Joseon dynasty (1392-1910). Emphasizing rightful criticism and the principles of virtue and merit in governance, Confucian ideology emphasized self-governance as a prerequisite for effective rule. This led to the establishment of the Offices of Censorate, responsible for monitoring the king, bureaucracy, and censorship. These bureaucratic constraints compelled successors of Sejong to initiate successive purges against perceived government adversaries.

During the Middle Joseon period, Korean history faced a pivotal moment with the Japanese invasion, marking a significant shift in regional dynamics. With China’s widespread influence in East Asia, Japan sought to expand its territorial control, proposing an “imperial road” through Korea. However, given the complex relationships stemming from the Choe regime and Mongol invasions, the Joseon Koreans vehemently rejected this demand, inciting outrage. Underestimating the superiority of Japanese warfare and their weaponry would be the first dent to the Joseon regime. Unlike the turbulent history of the Three Kingdoms era, the Joseon dynasty arose during a period of relative peace. While border skirmishes and internal power struggles occurred, the Joseon dynasty lacked direct combat experience, contrasting with Japan’s history of unified warfare under warlords. Furthermore, unlike Japan’s emphasis on grooming soldiers from youth, Confucian values during the Joseon rule prioritized education and scholarship as pathways to social success and hierarchy.

Imjin war – Invasion of Busan (left) and Japanese armour which consists of a yoroi (the body) and kabuto (helmet) for the head

Korea found salvation through a combination of Chinese intervention on land and naval triumphs led by Admiral Yi Sun-Shin. Under his leadership, the Korean navy, equipped with formidable “turtle boats” boasting metal plate protection against enemy fire arrows, achieved remarkable success. These innovative vessels were the world’s first ironclad warships. Yet, beyond the ships, it was Admiral Yi’s unparalleled knowledge of Korean waters and strategic planning that proved decisive in securing naval victories. His firsthand account of these events in his war diary, “Nanjung Ilgi,” offers invaluable insight into his campaigns against the Japanese invaders and has earned recognition on UNESCO’s International Memory of the World Registers.

The aftermath of the Imjin War was devastating for Korea, caught in the crossfire of Chinese and Japanese conflict. The conflict claimed the lives of 2 to 4 million Koreans and ravaged homes and farms across the countryside. Seoul’s five palaces lay in ruins, with reconstruction of the main palace delayed until 1865. In contrast, Japan suffered fewer losses, leaving its people and land relatively unscathed. Meanwhile, China’s Ming dynasty, depleted by the war effort, fell to the Manchu, who established the Qing dynasty in 1644. Seeking to secure allegiance, the Qing invaded Korea, further destabilizing the region by seizing the crown prince and his siblings.

The transition from Ming to Qing posed a moral quandary for Joseon Korea. While the Ming was regarded as the “older brother” in Confucian hierarchy, the Qing, as usurpers, lacked such status. This ethical dilemma spurred Joseon toward strict adherence to Confucian principles, with Korea assuming the mantle of orthodox Confucianism. This heightened orthodoxy led to meticulous observance of ceremonial rites, exacerbating social rigidity and contributing to the dynasty’s decline. Moreover, the invasions fueled deep-seated paranoia, prompting Korea to isolate itself from foreign influence. Foreign travel and visitors were banned, with limited trade permitted only with Japan. Despite acknowledging China’s dominance and the legitimacy of the Qing dynasty, Korea maintained a closed border along the Yalu River. This isolation earned Korea the moniker “Hermit Country,” with its doors shuttered to the outside world for four centuries until 1873.

However, complete isolationism is rarely sustainable. Within its sealed borders, Korea underwent changes, sometimes focusing on court rituals and inheritance rules to align with Confucian orthodoxy, while also experiencing intellectual ferment that analyzed society and human relations in new ways. Outside its borders, Western imperialism began to encroach. Western ideas trickled in through translated Western books brought by Korean envoys. Catholic missionaries showed interest in Korea as early as the 16th century, when the first Portuguese entourage arrived with the invading Japanese army. Many Koreans were drawn to Christianity, viewed as a more egalitarian alternative to Confucianism, and by the late 18th century, native Christians had emerged. By 1856, the Korean Catholic church boasted almost 17,000 faithful. However, the mid-1860s saw a shift towards isolationism, with the Regent leading the persecution of native and foreign Catholics, despite the growing popularity of Catholicism.

When Heungseon Daewongun assumed de facto control of the government in 1864 as the father of the minor King, there were twelve French Jesuit priests and an estimated 23,000 native Korean converts in Korea. Daewongun launched an effective campaign to control state policy and maintain isolation, especially in response to Western incursions in East Asia. The first attempt to open Korea for trade was made by America in 1866, but this was met with resistance. In the same year, a Hungarian adventurer named Ernst Oppert attempted to kidnap the bones of Regent Daewongun’s father, exploiting Confucian principles that dictated the fate of a man’s descendants based on where his ancestors’ bones were buried. In 1871, U.S. authorities sent an expedition to investigate the fate of the missing merchant ship SS General Sherman, and the French sent an expedition to inquire about reports of the execution of French priests in anti-Catholic purges. However, these incidents only reinforced Heungseon’s view of Westerners as barbarians, further entrenching Korea’s isolationist stance.

Unhyeongung Palace or the Royal Residence of Regent Heungseon and his family, including the Emperor Gojong, 26th king of the Joseon dynasty. The palace complex spanned all the way to Changdeokgung palace, the main palace at that time. The complex is a source of information into the last 5 decades of the Chosun period. Norakdang Hall and Noandang Hall were built in 1864, Irodang Hall and Yeongnodang Hall in 1969.

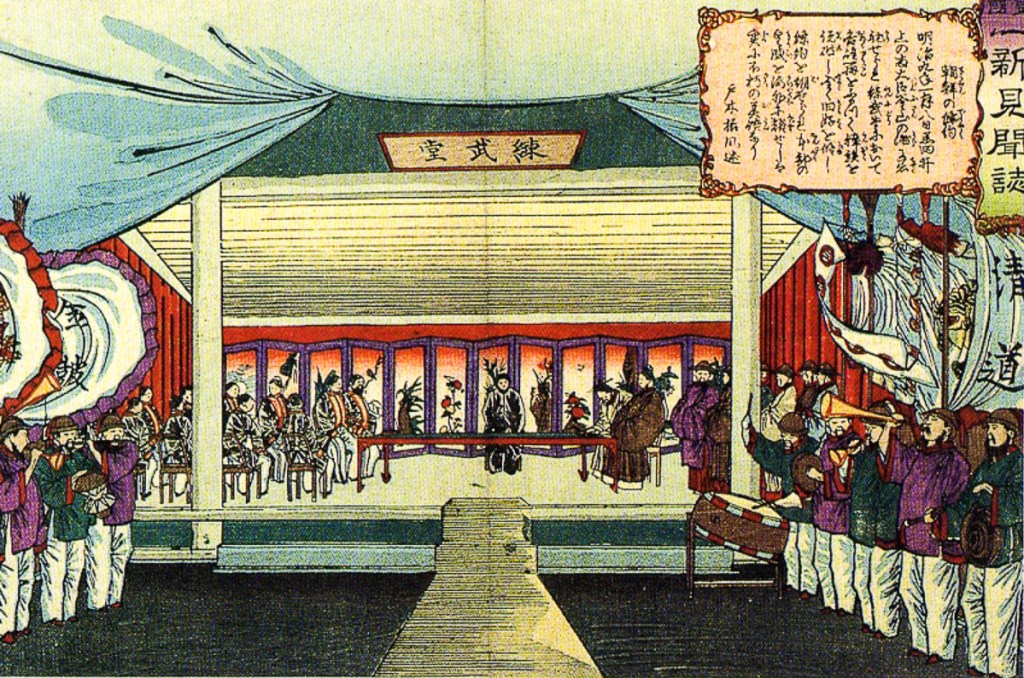

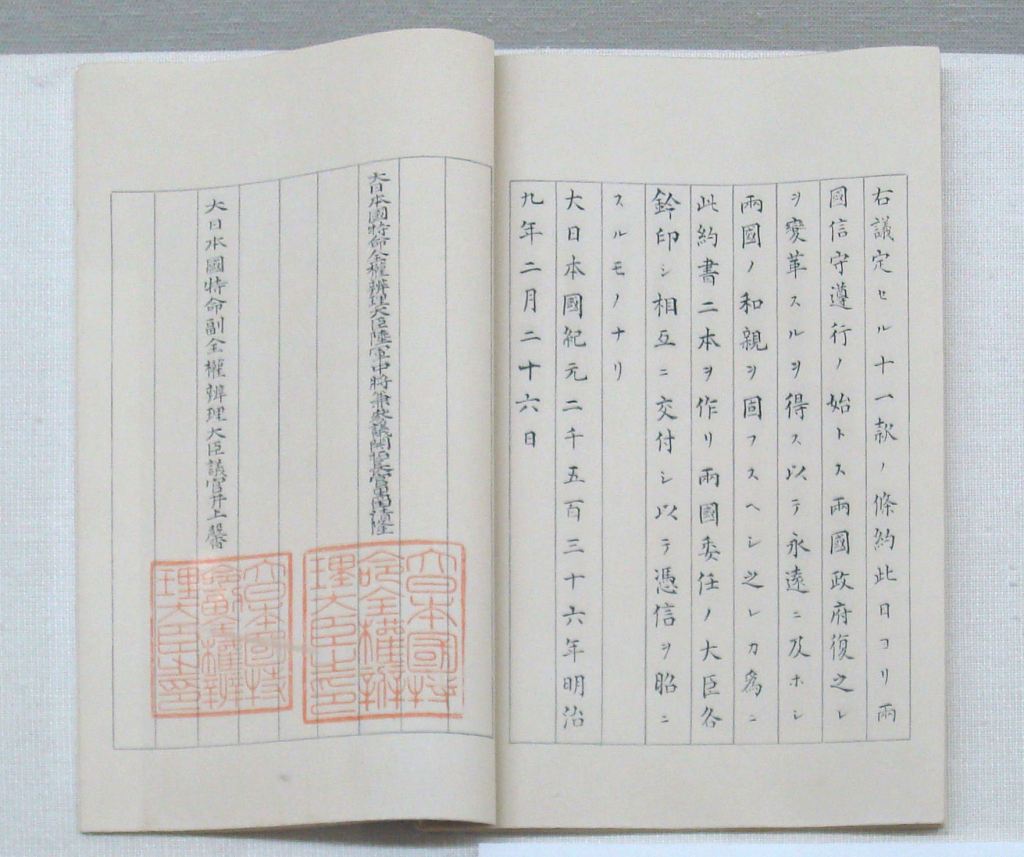

In 1876, Japan imposed the Ganghwa Treaty, an unequal pact of amity and trade. This treaty declared Korea’s independence from the Qing dynasty, ending its status as a tributary state. It also opened three ports to Japanese trade and included provisions that favored Japanese commercial interests. Subsequently, other powers signed similar treaties: the Americans in 1882, the British and Germans in 1882 (formally ratified in 1884), the Russians and Italians in 1884, and the French in 1886. China also sought closer ties with Korea. In 1897, King Gojong took steps to defend Korea’s sovereignty against foreign powers by renaming the state the Korean Empire and assuming the title of Emperor Gojong. Simultaneously, Emperor Gojong initiated the Gwangmu Reform from 1897 to 1907, aimed at modernizing and westernizing the Korean empire. These reforms laid the groundwork for future Korean development, focusing on infrastructure, economic reform, and the establishment of a modern bureaucracy and military. However, China’s defeat in the Sino-Japanese War of 1894-1895 left Korea vulnerable to attack.

The pivotal event that solidified Japanese colonial rule occurred with the brutal assassination of Queen Min (commonly known by her posthumous title, Empress Myeongseong) in the palace in October 1895, by Japanese samurai due to her pro-Chinese stance. Subsequently, the Russo-Japanese War of 1904–1905 resulted in another Japanese victory, further diminishing the status of the Korean empire. In 1910, Japan forcibly stripped Korea of its sovereignty, taking control of all national affairs and initiating the Japanese colonial period, which lasted until 1945 at the end of World War II. During this colonial period, Korea witnessed the establishment of modern institutions such as a civil service, a postal system, newspapers, banks, corporations, and trade associations, along with the rise of capitalism and its accompanying responses, including trade unions and leftist organizations. Consequently, Korean society shifted from one largely reliant on agriculture to one dominated by an industrial class and wage labor.

When considering the impact of Japanese colonization on Korea, the mere suggestion of Japan having “modernized” Korea evokes strong reactions of indignation and raw emotion among Koreans, both in the North and the South. It’s a sentiment shared by many former colonies worldwide, as few would speak fondly of the atrocities of the past. In the collective memory of Koreans today, Japan is associated with both the invasion of 1592 and the colonial takeover in 1910. Unlike the more traditional Confucian administration and cultural practices, Japanese rule brought a pervasive intrusiveness and efficiency that permeated all levels of Korean society. Reflecting on the 35 years of Korean history under Japanese colonial rule reveals subtle nuances left behind—cultural influences, personal memories, and technological advancements.

A prime illustration of Japanese influence in Korea can be found in the Baek In-je House in Gahoe-dong, Bukchon. Constructed in 1913 during the colonial period, this building represents a modern reinterpretation of the traditional hanok style. It features a two-story layout connecting the sarangchae (men’s quarters) and anchae (women’s quarters) through a hallway, a departure from the separate structures typically found in Joseon dynasty hanoks. Additionally, Japanese architectural elements such as tatami mats, red bricks, and glass windows, which were distinctive features of the time, can be observed in the design.

The period spanning from 1919 to 1931, known as the Cultural Policy Period, witnessed a flourishing of cultural creativity amidst subtle censorship and suppression. Following this, the Assimilation Period from 1931 to 1945 marked a feverish attempt by the Japanese authorities to eradicate Korean culture. Koreans recall how they were compelled to adopt Japanese names and were prohibited from using their own language or writing in their native alphabet. This memory serves as a core aspect of their historical consciousness, symbolizing the heavy-handed policies imposed by Japan in 1910, even though certain measures such as the name law and language prohibition were not fully enforced until 1939, during the later phase of the occupation, which was characterized by wartime conditions and extreme deprivation.

Beyond the erosion of cultural identity, one of the most egregious injustices inflicted upon Koreans was the establishment of the comfort corps—a euphemism for young women coerced into serving as prostitutes for Japanese soldiers. While the comfort corps included women from various backgrounds, including Japanese and those from other conquered territories such as China, the Philippines, Burma, Pacific Islands, and even a few Dutch women captured during Japan’s occupation of Indonesia, the largest contingent by far were Korean women, comprising as much as 80 percent according to some estimates.

Few issues evoke as strong a sense of nationalism among Koreans as the debate over the name of the body of water between Korea and Japan. While Korea adamantly advocates for calling it the East Sea, labeling it as the “Sea of Japan” can ignite passionate reactions. Another sensitive topic that stirs emotions is the issue of the Comfort Women. Initially shrouded in silence, the late 1980s saw a breaking of that silence. As the local guide explained during our walk through in DMZ, once the silence was broken, every year, silent vigil is held in Seoul with the hope that the current Japanese government will acknowledge the depravity committed, issue and apology and due reparations, and provide an official number that will help provide closure to many.

While Japan’s defeat liberated Korea from its colonial rule, the aftermath of World War II left a bitter taste due to geopolitical tensions between the United States and the Soviet Union. The Korean Peninsula itself was not heavily impacted by war-related casualties; instead, loss of unity and subsequent unrest overshadowed the peace that followed.

Following Japan’s surrender south of the 38th parallel, the Soviet Union established a communist regime in the North. Kim Il Sung arrived in the Soviet-occupied zone of Korea in October 1945, coinciding with Syngman Rhee’s arrival in the American-occupied zone. In 1947, the United Nations proposed supervised general elections, which North Korea rejected. On August 15, 1948, the Republic of Korea (South Korea) was declared, with Rhee becoming its first president. Less than a month later, on September 9, Kim Il Sung proclaimed the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK).

In 1949, the US reduced its defense, and on June 25, 1950, North Korea invaded South Korea. Koreans do not refer to it as the “Korean War” but rather as the “June 25 Incident,” marking the date when the sudden invasion of Seoul shocked the nation. Seoul, located dangerously close to the 38th parallel, fell within three days. The war, often dubbed the ‘‘Forgotten War,’’ resulted in 1.3 million dead and 2.8 million wounded, and it devastated one-fourth of the country’s resources and wealth, along with half of its infrastructure. Even today, Korea allocates 6% of its GNP annually to defense, boasting the fifth largest military force globally. Walking in the vicinity of the world’s most dangerous and active demilitarized zone serves as a haunting reminder of countless untold stories and the enduring aftermath of conflict.

The Compatriot’s Spirit stands as a distinctive installation within the War Memorial, symbolizing the current achievements of the Korean people, forged through unity in the face of adversity. The threads on either side of the knot represent the historical trials endured by the Korean race, while the knot itself symbolizes the Mugunghwa, or Rose of Sharon, the national flower of Korea. Notably, the concept of the Great Union represents the sole path known to Koreans, offering hope in overcoming national crises and restoring prosperity and cultural identity.

Despite the extensive length of this post, if you’ve made it all the way to the end, here’s a list of the places discussed herein.

| Seoul | Gyeongju |

| Bukchon Village | Gyeongju National Museum |

| Gyeongbokgung Palace | Cheomseongdae Observatory |

| Changdeokgung Palace | Bulguksa temple |

| Gwanghwamun Square | Daereungwon Tomb Park |

| Unhyeongung Palace | Cheonmachong |

| Jongmyo Shrine | Gyeongju Gyochon Traditional Village |

| Bongeunsa temple | |

| Jogyesa temple | |

| Myeongdong Cathedral | |

| National Hanguel Museum | |

| National Museum of Korea | |

| The War Memorial of Korea | |

| Seoul Station | |

| Bank of Korea | |

| Seodaemun Prison Museum | |

| Demilitarized Zone |

Recent (and not-so recent) Posts:

[…] Here’s the new post […]

LikeLike

[…] reasons, recent conflicts have started regarding the evolution history of Korean cuisine since China played such a dominant role in defining the history of Korean peninsula. The term “kimchi war” refers to a cultural dispute between Korea and its neighboring countries […]

LikeLike

[…] (left to right) showcases an airplane toilet, an automated smart toilet (my favorite during my travel in South Korea) and an incinerator […]

LikeLike