The title sounds like a zodiac sign mayhem. To be honest, I have been wracking my brain over this next blog piece. As you know, my posts often stem from personal musings, a whimsical thought, or a pun that tickles my fancy. Regardless of the inspiration, I always dive deep because, while history might not be my major, it’s definitely my major passion. So, this time, instead of diving into the classic “battle of the sexes,” let’s stir things up with a duel between monarchs! To keep things “relatively” simple and a bit different, I’m leaving the British monarchs out of this one. But fear not! If you’re itching for some British royal drama, you can always check out my previous post on the Tudors.

Ready for a royal rumble? Before we dive in, I must add this disclaimer. The Bavarian castles will call out to the photographer in your heart. While you can take your time with the exteriors, interiors are strictly forbidden. I may have been a bit of a rebel here as I sneaked in couple of pictures, but they are not my best work! Versailles, on the other hand, is a photographer’s paradise while a nightmare for those who hate crowds and want clean images. At times, because of the jostling and numerous group tours, I had to stop taking pictures and find a breathing room. So, as usual, I will attribute wherever the pictures are not mine. Moving on, 2023 was the year of European castles. And I found this quote to be a perfect representation of my adventures:

“The Earth is littered with the ruins of empires that believed they were eternal”

As you delve further in, here is an easy way to follow the organisation of this blog

Beyond Neuschwanstein: Other Castles

Sun vs Moon: The need for comparison

Two monarchs, separated by nearly two centuries yet united by a shared obsession with kingly grandeur and authority, offer a remarkable contrast. Both men claimed their respective crowns at a devastatingly young age and quickly learned to distrust their kingdoms’ nobility. This mutual cynicism, combined with their shared zeal for self-mythologizing through lavish architectural ambition, propelled them into staggering realms of creative excess — and catastrophic debt. Louis’ absolutism drained the French coffers through perpetual warmongering. Ludwig’s make-believe world-building drained the Bavarian royal finances to utter collapse.

“Do not follow the bad example that I have set for you,” a dying Louis told his heir. “I have often undertaken war too lightly and have sustained it for vanity. Do not imitate me, but be a peaceful prince.”

The connection between these two kings goes beyond their architectural legacies and touches on their very names. The evolution of the name ‘Louis’ traces back to the first king to unite the Franks, Hlodowig, whose name was Latinized to ‘Clovis’ after his conquest of Gaul. As the Franks expanded their territories, the name ‘Clovis’ morphed into different forms across regions. In France, it became ‘Louis’ when the Franks dropped the ‘c’ and the ‘s.’ In Iberia, it transformed into ‘Luis,’ in Italy, ‘Luigi,’ and in Germany, ‘Ludwig.’ Intermarriage with the Hungarians even resulted in the name Lajos.

Both monarchs, through their architectural masterpieces, sought to immortalize their visions of kingship. Ludwig II’s Neuschwanstein, perched on a hill and shrouded in mist, embodies the dreamlike quality of a bygone era. In contrast, Louis XIV’s Versailles, with its sun-drenched splendor, reflects the tangible might and opulence of a ruler who saw himself as the center of the universe.

Ultimately, it was their obsession with their grand dreams that led to the downfall of two kings lost in their own fantasies, disconnected from reality by their overwhelming egos. Louis XIV’s relentless pursuit of power coupled with extravagant spending fueled a revolution that toppled the French monarchy, paving the way for human rights and freedom. Meanwhile, Ludwig’s eccentric fantasies led to his deposition as a madman, and his mysterious death while chasing the unreachable heights of Romanticism.

The Sun King

“I depart, but the state will always remain.”

Last words of Louis XIV on his deathbed.

Few monarchs have ruled longer or left as indelible a mark on history as Louis XIV of France. Born in 1638, he ascended the throne at the tender age of four after the death of his father, Louis XIII, and ruled for an astonishing 72 years. His reign remains the longest of any European monarch, and his legacy continues to influence modern France and the broader European landscape. His birth miraculously earned him the name Louis-Dieudonné, meaning “gift of God.” This would be the first step towards his profound narcissism in my opinion.

His early years were marked by the Fronde civil wars, which forced him to flee Paris twice and ingrained a deep distrust of the nobility. After Mazarin’s death in 1661, Louis declared independence without a chief minister, allowing him to centralize power and maintain control over state affairs. This hands-on approach solidified his authority and reshaped the French monarchy into an absolute monarchy, with Louis at its core.

Louis XIV’s vision of kingship can be described by the concept of gravitation—just as the sun is the center of the universe, he believed he should be the center of his court, and by extension, that France should be the center of global politics. He firmly believed his authority was granted directly by God, making him answerable only to the divine. This notion of divine right justified his absolute control, freeing him from the constraints of other political entities. This idea is vividly reflected throughout the 700 rooms of Versailles, where the sun and Fleur-de-lis are prominent symbols.

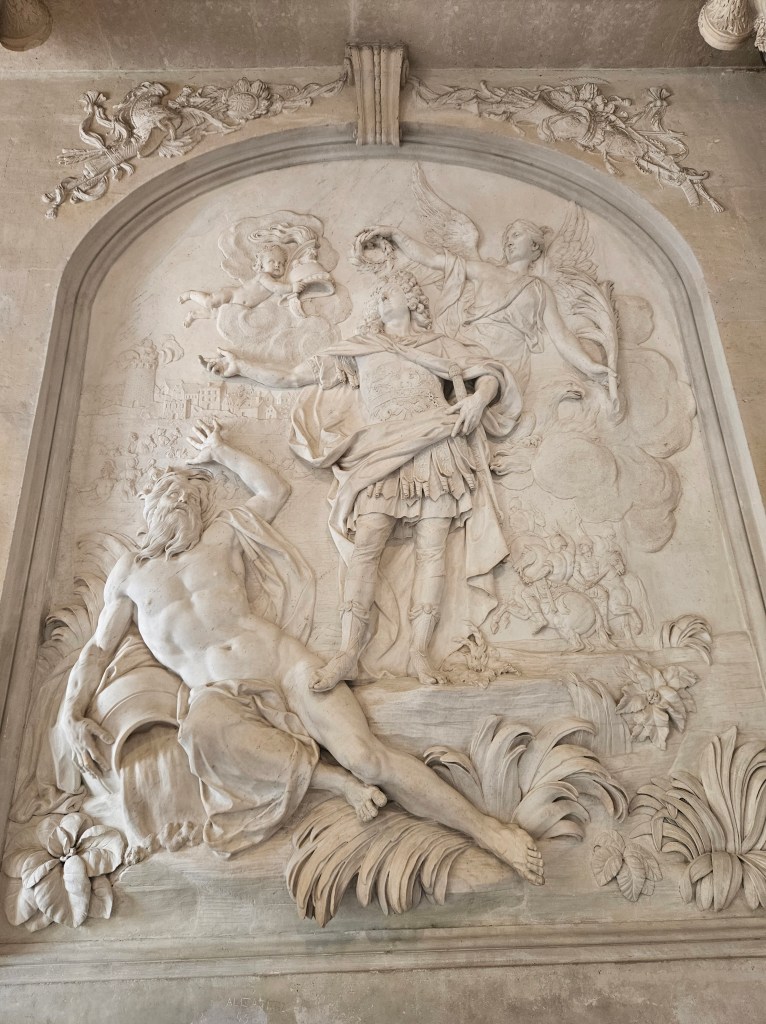

Louis XIV adopted the sun as his emblem, drawing parallels to Apollo, the Greek and Roman sun god, to cultivate an image of himself as the omniscient and infallible “Roi-Soleil” or Sun King. Like Apollo, Louis XIV saw himself as the source of light and life for his kingdom. He even took on the role of Apollo in a royal ballet, underscoring his self-image as a divine being. Throughout the palace, you’ll find representations of the sun god, from laurel wreaths to lyres and tripods. In every way, Louis XIV’s reign was a carefully crafted spectacle of power and divinity, with Versailles as its grand stage.

Initially, Louis XIV’s reign was characterized by frequent relocations of the royal court. Until the official inauguration of the Palace of Versailles on 6 May 1682, the King and his courtiers moved between various royal residences including the Louvre Palace, the Tuileries, and the Châteaux of Saint-Germain-en-Laye, Vincennes, Fontainebleau, and the rapidly-developing Versailles. This constant movement ceased once Versailles was ready to serve as the ultimate symbol of royal absolutism and splendor.

Entrusting Europe’s master architects, designers and craftsmen with what he termed his “glory,” he spent a huge amount of taxpayer money on Versailles and its more than 2,000 rooms, elaborate gardens, fountains, private zoo, roman style baths (for frolicking with his mistress) and novel elevators. André Le Nôtre, the renowned landscape architect, was responsible for the vast and intricate gardens. Louis Le Vau, who served as the First Architect to King Louis XIV, designed significant portions of the palace including the State Apartments and the garden façade.

The Garden of Versailles

By shaping nature, men can exert control over their surroundings and create small paradises modeled after their own ideal of beauty… Louis XIV became an orchestrator, not only of nature but also of how visitors viewed this landscape. The gardens of Versailles are not natural; rather they represent the triumph of man over nature. As the Sun King, he imposed absolute control over nature, subjugating wilderness to his own ideal of beauty.

The Versailles palace had extensive gardens covering 3 square miles, featuring symmetrical formal gardens, sculptures, ponds, a canal, and numerous fountains.In fact, Versailles is often referred to as the largest open-air sculpture museum in the world, boasting 386 works of art made from bronze, marble, and lead, with 221 of these sculptures adorning its magnificent gardens. To maintain the design, the garden needed to be replanted approximately once every 100 years, a practice carried out by Louis XVI and Napoleon III. André Le Nôtre organized the gardens around two axes: north-south and east-west, starting at the Neptune Fountain and continuing to the Orangery and Lake of the Swiss Guard. The Grande Perspective, a symmetry axis, bisects the gardens, showcasing the French formal garden’s optical effects. The idea of the French Garden was to showcase to the world the French of taming of chaos into civility and manners – a symbolism that reiterates the Sun King’s absolute narcissism.

The palace garden is designed around alleys parallel to the Royal Way and groves, with four fountains dedicated to the four seasons: Spring, Summer, Autumn, and Winter. Roaming around the garden itself feels like a challenge for finding fountains. Latona’s fountain (first images in top row of the gallery below), created in 1668, was inspired by The Metamorphoses by Ovide. It illustrates the story of Latona, the mother of Apollo and Diana, protecting her children from the insults of the peasants of Lycia and pleading with Jupiter to avenge her. The god obliges by turning the inhabitants of Lycia into frogs and lizards.

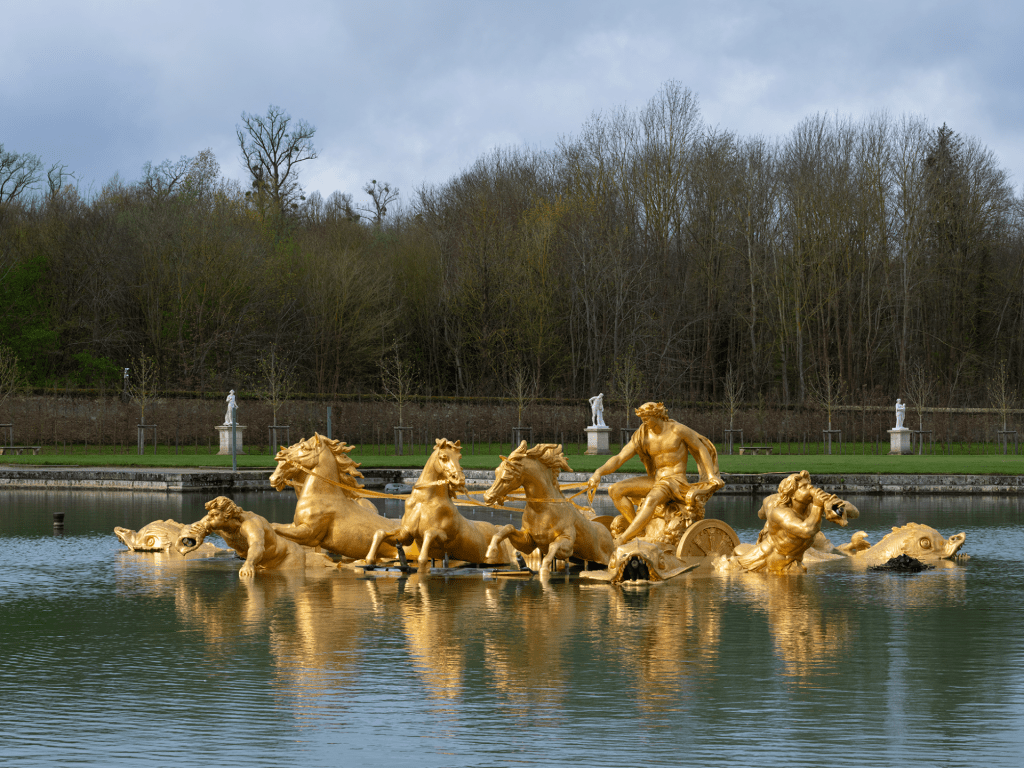

A water feature already existed here in 1636, during the reign of Louis XIII, and was known as the Lake of the Swans. Louis XIV later added the spectacular and famous work in gilded lead of Apollo riding his chariot (last image in the gallery). This piece, built by Tuby on a design by Le Brun, is based on the legend of Apollo, the Sun god and the King’s icon. It features the god bursting forth from the water in anticipation of his daily flight above the earth. Tuby made this monumental group in the Gobelins manufacture between 1668 and 1670, when it was transported to Versailles and put in place and gilded the following year. At the time of my visit to the garden, the Apollo’s fountain was undergoing maintenance because of the upcoming Paris Olympics 2024.

Under the reign of Louis XIV the gardens of Versailles contained fifteen groves. Contrasting with the strict regularity of the general layout of the gardens, they had a variety of décors and shapes. The Ballroom Grove was the last grove to be laid out in the gardens by Le Nôtre. The works began in 1680 and were completed in 1685. The Grand Dauphin, the son of Louis XIV, organized a great dinner there to celebrate its inauguration. The grove was designed as an amphitheater of greenery, intended for dancing. In fact, at the time of my visit, some of my fellow visitors decided to honor the old tradition and work up some waltz befitting the atmosphere!

Commenced in 1685 by Jules Hardouin-Mansart, the Colonnade Grove replaced the Spring Grove created by Le Nôtre in 1679. In the centre, the original pool was replaced in 1696 by the group sculpture by Girardon showing The Abduction of Persephone by Hades.

Apollo’s Baths Grove was probably my favorite, especially considering the famous Apollo’s fountain was out of commission. It dates from the reign of Louis XVI and was laid out between 1778 and 1781. In the same location, Le Nôtre initially installed the picturesque Marsh Grove in 1670, its principal decoration consisting of a pool bordered by lifelike painted metal reeds and adorned in its centre by a metal tree with a fountain springing from it. In 1705 this fantastical grove was eliminated to make room for the groups Apollo Served by Nymphs and Horses of the Sun, which Jules Hardouin-Mansart placed under gilded lead canopies and on pedestals surrounded by a pool.

The french style: versailles interiors

Louis XIV’s astronomical expenditure stimulated a huge expansion of French crafts and specialist applied art, led directly to the emergence of Rococo art (dominated by France), and created an momentum for French painting and sculpture that paved the way for Paris to become the arts capital of the world. The Apollo Salon at Versailles is a dedication to the Roman god of the sun. It was initially designed as the King’s chamber before becoming the throne room. Until 1689, it housed a 2.60 metre throne which was melted down in order to pay for costly wars. All the other furniture – of solid silver – were also melted down. Today a gilded wooden chair has been placed on a dais on a Persian carpet.

Over the fireplace is the most famous portrait of Louis XIV, by Hyacinthe Rigaud. The painter made the original portrait in 1701 upon a personal request by the king, who wanted to give it to his grandson who had recently become king of Spain. Exceedingly pleased with the result, Louis XIV decided to keep the original for himself and commissioned copies from the artist. The copy in Versailles was made in 1702. The original painting hangs now in the Musée du Louvre. The ceiling paintings of the room consists of “Apollo in the Chariot of the Sun accompanied by the Seasons” by Chalres de la Fosse. The arches in the vault illustrate the king’s magnificence and magnanimity though various examples from Antiquity such as Vespasien building the Colosseum; Augustus building the port of Miseno, Porus before Alexander and Coriolan entreated by his wife and mother to spare Rome.

Following Le Vau’s death, Jules Hardouin-Mansart took over as First Architect to the King in 1681, overseeing the completion of the palace and the construction of the Grand Trianon. He was also in charge of the design of the infamous Hall of Mirrors that took 6 years to complete. Charles Le Brun, the First Painter to the King, adorned the interiors with elaborate decorations such as the fleur-de-lis and the royal sun, into the architectural details, creating what came to be known as “the French style.” The 30 painted compositions on the vaulted ceiling by Charles Le Brun depict the glorious history of Louis XIV’s reign from 1661 to the peace treaties of Nijmegen in 1678. These artworks celebrate the political, military, and economic triumphs of France, illustrating Louis XIV’s role as the arbitrator of Europe.

There’s an interesting philosophy that was shared with us by the tour operator – There was a distinct order in the design of Versaille from a mere hunting lodge to an opulent palace. The Garden was laid out on an east–west axis in order to mimic the course of the sun: the sun rose over the Court of Honor, lit the Marble Court, crossed the Chateau and lit the bedroom of the King, and set at the end of the Grand Canal, reflected in the mirrors of the Hall of Mirrors.

Mirror might be an everyday object to you and I, but it clearly was a far more opulent symbol in 17th century Europe. The abundance of mirrors, a luxury item at the time, demonstrated France’s ability to rival the Venetian monopoly on mirror manufacturing. Louis XIV even enticed Venetian artisans to France to produce these mirrors, showcasing the nation’s burgeoning economic power and craftsmanship. It was built to replace a large terrace that connected the King’s apartments to the Queens’s.

Daily life at Versailles saw courtiers and visitors traversing the Hall of Mirrors, using it as a grand passageway or a place to meet with the sovereign. In Louis XIII’s time, the room that eventually became the King’s Chamber, or bedroom, was a reception room. Where the bed stands now, windows provided a view of the gardens. Louis XIV had the room closed off to serve as his bedchamber. Each morning, a crowd of courtiers would watch as he was washed, shaved, and dressed in a ceremony known as the First Levee. At night, the king’s retirement to bed—the Coucher—was also witnessed.

As the official seat of absolute monarchy from 1682 to 1789, Versailles was a hub of scientific advancement, thanks to the influence of the Royal Academy. Founded in 1666, this prestigious institution forged a unique partnership between royal power and scientists, all dedicated to serving the kingdom’s interests. The sciences and techniques not only played a crucial role in the construction and aesthetic grandeur of Versailles but were also celebrated in the elaborate ceiling decorations of the grand apartments and private cabinets.

These artistic depictions, however, were more allegorical than rational. They symbolized the diverse realms of royal influence: trade, war, the navy, the arts, and agriculture. In this way, science and its instruments were interwoven into the very fabric of royal identity and function, illustrating the profound connection between knowledge and power in the era of Versailles.

The Hall of Mirrors is known for its epic proportions, stretching 73 meters long, 10.4 meters wide, with a ceiling height of 12.2 meters. This vast space is accentuated by seventeen arcade windows overlooking the gardens, mirrored by seventeen arches adorned with a total of 357 mirrors. In homage to Louis XIV’s nickname, the Sun King, the Hall of Mirrors’ barrel-vaulted ceiling is hung with a series of crystal chandeliers that glitter with reflected light from the mirrors. The chandeliers originally bore candles, but are now electrified.

In the gallery above, the first image has been taken from google, while the other three are from my collection.

Seventeen lofty windows are matched by as many Venetian framed mirrors. Between each window and each mirror are pilasters designed by Coyzevox, Tubi and Caffieri—reigning masters of their time…Walls are of marble embellished with bronze-gilt trophies; large niches contain statues in the antique style.

Francis Loring Payne description of the 240-foot-long hall in The Story of Versailles

The Hall of Mirrors was known to host significant ceremonies and events, such as the wedding of Louis XVI to Marie-Antoinette in 1745. On 28 June 1919, this opulent grandeur bore witness to the signing of the Treaty of Versailles, marking the end of World War I. This event was attended by 27 delegations representing 32 powers, making it a poignant location for the treaty that profoundly affected the geopolitical landscape. The hall had witnessed the proclamation of the German Empire in 1871, following France’s defeat in the Franco-Prussian War, as well as Germany’s downfall as it was held solely responsible for the war and stripped of its empire.

During his coronation, Louis XIV pledged to defend the Catholic faith, a vow he honored by persecuting religious dissenters. This included cracking down on the Jansenists and revoking the Edict of Nantes in 1685, which had previously granted religious tolerance to Protestants. Consequently, Protestants were forced to convert, and over two hundred thousand fled France.

The Royal Chapel at Versailles, Louis XIV’s final grand project and his enduring spiritual legacy, stands as one of the palace’s most dazzling gems, rivaling even the famed Hall of Mirrors. Although the project was officially announced in 1682, construction didn’t commence until 1699 and was completed in 1710. The chapel emerged as a magnificent masterpiece of sacred architecture, showcasing the pinnacle of artistic achievement of its time. Its intricate design and ornate details make it a treasure trove of the Baroque era, reflecting the grandeur and devoutness of the Sun King’s reign.

The Moon King

Even before he died, the king had already become something of a legend.

“I want to remain an eternal mystery to myself and others”, Ludwig once told his governess.

When discussing iconic figures whose legacies blend myth, architecture, and personal tragedy, few names resonate as powerfully as King Ludwig II of Bavaria.

He is known by many nicknames: the Swan King, the Mad King of Bavaria, the Dream King, and Mad Ludwig. But more popularly, he is “der Märchenkönig” or the “Fairy Tale King,” the romantic king who was spellbound by the mythical worlds of Germanic folklore and Wagner’s majestic operas at a very early age. He reveled in imaginings of brave knights, fair maidens, and the mystical grail quest – all represented in the extraordinary castles he would build as an eccentric refuge from mundane reality.

Although Ludwig II (1845–1886) was born in Munich and is also buried there, the city never held his affection. Known as the Fairytale King, Ludwig much preferred the solitude of his castles nestled in the Alpine foothills. In a letter to the Earl of Dürckheim, he described Munich as a “hated, unlucky city.” He had little regard for its citizens, dismissing them as “idlers and philistines,” and the idea of connecting with the common people was entirely foreign to him.

Ludwig II’s fascination with the fantastical began in his childhood. Born to King Maximilian II and Queen Marie of Bavaria, Ludwig was more captivated by legends and operatic grandeur than by the political duties expected of him. His summers were spent at Hohenschwangau Castle, surrounded by murals of medieval legends, which sparked his imagination. The natural beauty and historical richness of his surroundings, especially the ruins above Hohenschwangau, inspired young Ludwig to dream of creating his own castle—a dream he would later pursue with fervor.

At the age of eighteen, Ludwig’s life took a dramatic turn when his father died suddenly in 1864. Thrust onto the throne, Ludwig found himself unprepared for the political realities of kingship. His retreat into a world of fantasy deepened as he sought solace in grand architectural projects that would become his legacy.

While Louis XIV glory was absolute and redefined as the Sun King, Ludwig called himself the Moon King. He often stayed up all night and slept all day. He was fond of moonlit sleigh rides. Pulled by four white horses, he rode in solitary splendor, enjoying the spectacular Bavarian landscape of mountains, foothills and farms. Unlike Louis XIV, Ludwig did not invest in military or participate in any battles, but he built some of the most beautiful Castles in the world. Ludwig was the only King who managed to spend a family patrimony gained over eight centuries in a very short time and all for building Castles. He inherited both the brilliance and the eccentricity of his lineage, shaping his reign and his remarkable, if tragic, legacy. Both his parents came from lines where cousins married cousins, a common practice among royalty to keep power and wealth within the family. However, this led to a higher likelihood of inheriting recessive traits, a reality the Bavarian royal family, the Wittelsbachs, knew well. For example, Ludwig’s aunt Alexandra believed she had swallowed a glass piano, and his aunt Marie was obsessed with cleanliness, wearing only white to spot any dirt. So was it really a surprise that the King inherited eccentricities as his family heirloom?

Castle of dreams

“rebuild old castle ruin of Hohenschwangau…in the authentic style of the old German knights’ castles.”

Ludwig II outlines his intentions with Neuschwanstein Castle in a letter to his friend, German composer Richard Wagner

Neuschwanstein Castle, perhaps the most famous of Ludwig’s creations, perfectly captures his fairy-tale vision. The castle’s name, which translates to “New Swan Stone,” evokes a sense of whimsy and legend. Originally dubbed New Hohenschwangau Castle, it was intended to be a grand recreation of Hohenschwangau Castle, where Ludwig spent his childhood. Today, the older Schloss Hohenschwangau stands in the magnificent shadow of Neuschwanstein. Interestingly, the name “Neuschwanstein” only came into use after Ludwig’s death, likely inspired by the Swan Knight, a character from the operas of Richard Wagner, whom Ludwig deeply admired.

Instead of an architect, Ludwig chose a stage designer Christian Jank to help him create the castle of his dreams since his plan was to create a real-life set where he could live within scenes of his favorite German tales and Wagner operas. Construction began in 1869, and the castle quickly became a blend of medieval romance and cutting-edge 19th-century technology such as centrally heated rooms with a hot air system, and modern kitchen featuring ducts beneath the floor to carry smoke from the oven to the chimney. Ludwig was deeply involved in every aspect of the castle’s construction, often making last-minute changes that frustrated his architects and builders. His impatience and perfectionism drove the project forward, but it also led to numerous delays and increased costs. According to plans, the castle was meant to have more than 200 rooms, but just over a dozen were finished before funds for the project were cut.

His only goal was to create Neuschwanstein as a personal refuge, a place where he could escape from the pressures of kingship and immerse himself in the operatic worlds of Richard Wagner, his favorite composer. Built for both political and deeply personal reasons, the castle reflects Ludwig’s response to the tumultuous events of 1866. After Prussia’s victory in the Austro-Prussian War, Bavaria was forced into an alliance with the empire, effectively stripping Ludwig of his power. In this context, Neuschwanstein became the centerpiece of Ludwig’s imagined kingdom, a place where he could reign as a true monarch in his own right. If we have to draw parallels, Ludwig was a Walt Disney ahead of his time. He would have definitely loved Disney’s quote: “If you can dream it, you can achieve it.“

The interiors of Neuschwanstein are a lavish tribute to Wagner’s operas, featuring scenes from “Lohengrin,” “Tannhäuser,” and “Parsifal.” The overall grandiose designs reflect Ludwig’s fascination with medieval knighthood and Christian mysticism. Mind you, since the interiors are part of a guided tour, photography is strictly prohibited. These were the few that I managed to capture just because I had to. And to be honest, I did get caught while being sneaky!

Yet, despite its splendor, Neuschwanstein was never completed during Ludwig’s lifetime. Unlike the fairy tales with happy endings, no queen, prince or princess ever lived in this fairy tale castle. The king spent only 172 days in residence before his mysterious death in 1886. Neuschwanstein, opened to the public just weeks after his demise, became a symbol of Bavaria’s romantic heritage. With its striking white limestone façade and deep blue turrets, Neuschwanstein is often rumored to be the real-life inspiration for the castle in Disney’s classic film, Cinderella, released in 1950. However, there’s another Disney castle that bears a remarkable likeness to Neuschwanstein: Sleeping Beauty’s Castle in Disneyland. Before Walt Disney began constructing his California theme park, he and his wife took a trip to Europe, which included a visit to Neuschwanstein Castle. Representatives from Disneyland later confirmed to The Orange County Register that Disney indeed had Ludwig II’s remarkable home in mind when envisioning Sleeping Beauty’s fairy tale palace.

But it’s not just Neuschwanstein’s lavish, fairy-tale design that has made the castle famous. Its role as a depot for Nazi-looted artworks during World War II has also made it rather infamous, as featured in George Clooney’s 2014 film “The Monuments Men.” After German troops invaded neighboring France in 1940, Adolf Hitler authorized the task force led by Alfred Rosenberg to “search libraries, archives, lodges and other philosophical and cultural institutions of all kinds for appropriate material and to seize such material,” which included cultural holdings by Jews, as noted on the Smithsonian Institution’s American Archives of Art and at the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum sites. Between 1940 and 1945, Nazi officials transferred stolen valuables, primarily from Jews, to locations throughout Europe, and later, to Germany, including salt mines, monasteries and castles. Neuschwanstein Castle was ideal as a depot and site for the Rosenberg taskforce headquarters since it was tucked away near the Austrian border, far from the capital Berlin or other likely Allied targets, and provided ample space.

The castle’s use during the Nazi era underscores the stark contrast between Ludwig’s vision of beauty and fantasy and the harsh realities of 20th-century history. Despite this dark chapter, Neuschwanstein emerged from the war largely unscathed, allowing it to continue serving as a symbol of Ludwig’s romantic idealism.

Beyond Neuschwanstein: Other Castles

Ludwig’s architectural ambitions were not limited to Neuschwanstein. An 1867 visit to the Palace of Versailles in France had brought the lifestyle of Kings Louis XIV, XV, and XVI to life for Ludwig. He loved the the opulence and aristocratic feel of the palace. Just as the Jugend Mountain had been an ideal setting for Neuschwanstein, the isolated Graswang Valley was perfect for his next creation, called Linderhof. Schloss Linderhof, a smaller but equally opulent palace, was inspired by the French Rococo style. Instead of deep, dark wood paneling and heavy murals, Ludwig chose gold, gold and more gold for his palace. Unlike the sunny south-facing bedroom of Versailles, Ludwig’s bedroom faced north, perhaps symbolizing his identity as the Moon King in contrast to Louis XIV’s Sun King. Outside his window, a stunning series of thirty terraced marble steps cascaded water into a statue-filled pool.

Since the landscape at Linderhof was unsuitable for a copy of the grand Palace of Versaille, he found another option for grand aspirations. In 1873, King Ludwig II of Bavaria acquired Herreninsel to construct his Royal Palace of Herrenchiemsee, a “Temple of Fame” dedicated to King Louis XIV of France, whom Ludwig greatly admired. Modeled after Versailles, this Bavarian Versailles began taking shape in 1878 under the direction of architect Georg Dollmann, following thirteen meticulous planning stages. Although Ludwig II’s death in 1886 left the palace incomplete, the sections that remain showcase its intended grandeur. Highlights include the opulent State Staircase, the majestic State Bedroom, and the breathtaking Great Hall of Mirrors.

Despite his initial disdain for Munich, Ludwig II now enjoys astonishing popularity in the city. Numerous busts and monuments honor his memory, and those wishing to walk in his footsteps can visit Schloss Nymphenburg, where Ludwig II was born in 1845.

A bust of the crown prince as a boy now stands in the room where he was born, and his magnificent carriages and sleighs are exhibited in the Marstallmuseum (Carriage Museum) at Schloss Nymphenburg, along with a collection of paintings of his favorite horses. In fact,

As an adult, Ludwig occupied an apartment on the third floor of the northwest pavilion in the Residenz palace, the Wittelsbach family’s city palace in the heart of Munich. From here, he frequently visited the Cuvilliés Theatre and the National Theatre, where he enjoyed numerous private performances between 1872 and 1885.

Moral of the Story

So while their reigns were defined by seeming polar opposite obsessions — the Sun King’s thirst for supreme authority over man, the Mad King’s sublime fantasies of escaping the mortal plane — both Louis and Ludwig remain inextricably linked. Louis XIV had no patience for such fanciful inspirations, whereas Ludwig governed as a tortured loner, crafting a universe of sublime isolationism. The Sun King held court in perpetual adulation, with courtiers attending his every move as a celestial deity among mortals. Ludwig’s need for own time were substantiated with spectacular constructions that may have been technological marvels in their own right, but stood largely deserted and neglected in his lifetime. What did you thing of this Royal duel?

Now the Pro tips:

- Versailles Tour Recommendation: Versailles is closed on Mondays – so make sure you plan your visits for Tuesday through Sunday. I toured Versailles with Fat Tire Tours, opting for their Versailles Château & Gardens Walking Tour. They handle all arrangements, including your metro tickets to Versailles, and entrance tickets to the palace and gardens. Just make sure to reach the pickup point on time.

- Exploring Bavaria: For traveling around Bavaria, I recommend getting a DB Card. This monthly subscription card, priced at 49 euros, allows unlimited travel within Germany. Even though we stayed for only seven days, it was incredibly useful for intercity transportation. Note that there are specific rules for the DB Card, including a limited window for cancellation. Be sure to read up on the details.

- Touring Bavaria’s Fairy Tale Castles: We chose a skip-the-line tour to visit Neuschwanstein, Linderhof, and Oberammergau, which made our experience hassle-free. You can read up about the fairy tale town of Oberammergau. Unfortunately, we didn’t visit Hohenschwangau Castle or Herrenchiemsee New Palace, so I can’t provide tour details for those. For Munich Residence and Schloss Nymphenburg, my recommendation would be to explore them on your own since they are located within Munich only.

Further Readings

- Louise XIV in history and the French Revolution

- French Kings names Louis

- Versailles Estate: All about the Gardens

- Elements of French Garden design

- Versailles Interior

- Versailles Hall of Mirror

- Sciences at Versailles

- The Versailles Knock-Off

- Bayern ticket train

- Deutschalnd ticket: a step-by-step guide

- Deutschland ticket

- Not So Happily Ever After: The Tale of King Ludwig II by Susan Barnett Braun

- The Swan King: Ludwig II of Bavaria

- The Castles of King Ludwig II

- Fairy Tale Castle

- The Real Monuments Men

- The True Story of Monuments Men

- Neuschwanstein’s dark past

Recent (and not-so recent) Posts: