Growing up as a June baby, my summer holidays climaxed in May, and come June, it was time to stock up on textbooks for the next academic year and prepare for the monsoon season. The temperament of June hasn’t changed much since then—still hot and dreary until the monsoons finally creep in around the 12th. Regardless of the weather gods, in 2016, I made a resolution to celebrate my birthday in a new country each year, if possible. That year, Bhutan was the destination of choice. By August 2017, I found myself in the UK, so naturally, June 2018 was celebrated in the United Kingdom. My first European birthday took place in Greece in 2019. Unfortunately, COVID-19 put a two-year halt on all my plans, though I do wish it had paused the aging process as well. For 2023, I decided to venture back to the European continent, planning a trip through France, UK, and Italy.

This blog post is dedicated to solely to Paris, and its warm embrace on June 12th. Unlike the usual knowledge on things to do in Paris, I have used the perspective of history and the Parisian life that I encountered during my visit. Here’s an easy outline for you:

Roman Settlements to Dummy Cities

Paris’s history stretches back over 2,000 years, evolving from a Roman settlement Lutetia and into the city that we know today. It built seven fortification walls to protect itself as a commerce port. The city’s journey as a capital started in 508 AD with King Clovis, although it wasn’t until King Philippe Auguste’s reign that Paris firmly established its status as the capital. During World War I, French authorities constructed a dummy city on the northern outskirts to deceive German bombers. This fake Paris featured replica streets and landmarks, including the Eiffel Tower and Gare du Nord. However, the decoy was not completed before the last German air raid in September 1918 and was dismantled after the war.

During World War II, the capital moved from Paris to Vichy from 1940 to 1944 under German occupation. A plaque marks the memorial honoring the 200,000 people who were deported from France to German concentration camps during World War II.

Spectacles to Skeletons: Unearthing Paris’s Dark Charms

Gothic Towers and Guillotines

The Conciergerie, the oldest part of the Palais de la Cité, was built during the reign of King Philippe Le Bel and features Gothic architecture and turrets that has served various roles- from royal residence to a state prison. The name “Conciergerie” derives from the “Concierge,” a high-ranking official appointed by the king to maintain order and oversee the police and prison registry. Despite its grandeur, the prison’s proximity to the Seine River often led to flooding, resulting in uncomfortable conditions for commoners who slept on damp straw.

During the French Revolution, the Revolutionary Tribunal operated from the Conciergerie, sentencing over 2,500 people to death by guillotine within its walls. The most famous prisoner was Queen Marie-Antoinette, who spent her last 76 days in the Conciergerie before her execution in 1793.

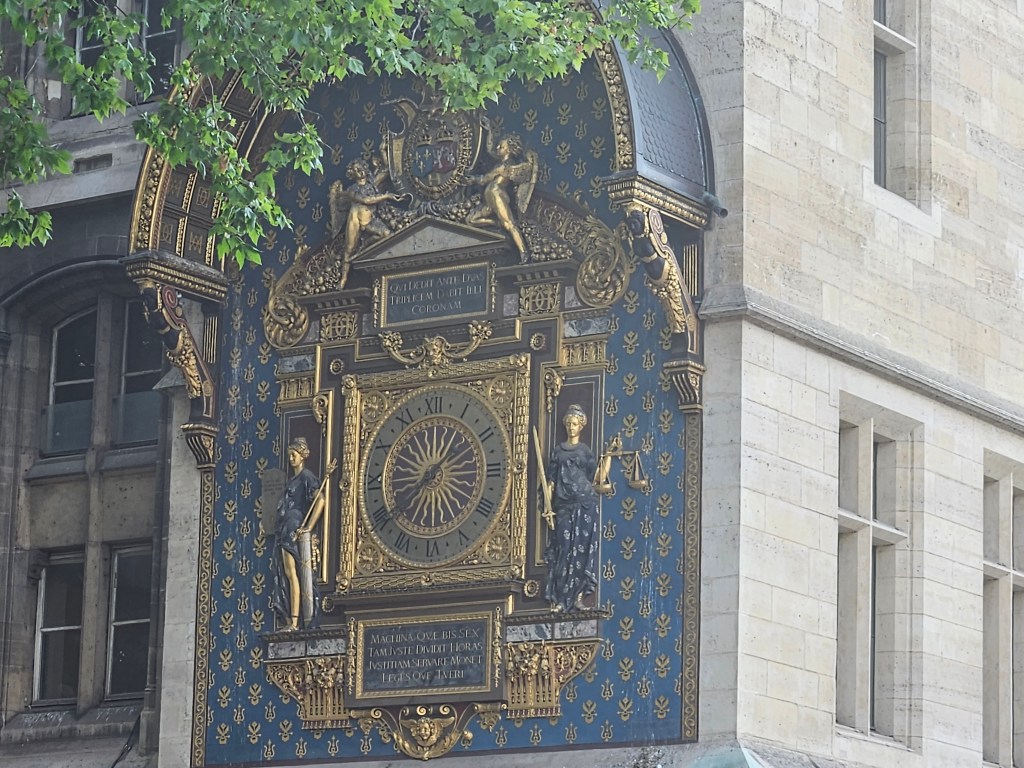

The Conciergerie also houses one of Paris’s oldest public clocks, commissioned by King Charles V in 1371, which has regulated Parisian activities for over 650 years. A Latin inscription is found below the clock: ‘MACHINA QUAE BIS SEX TAM JUSTE DIVIDIT HORAS, JUSTITIAM SERVARE MONET LEGESQUE TUERI’ which is translated in English as: ‘This mechanism which divides time into perfectly equal twelve hours helps you to protect justice and defend the law’.

The Ghastly Glamour of the Morgue

When you see compare the cause of why tourists seek Paris today, it’s hard to believe that in the past, a completely different kind of attraction drew crowds: the Morgue of Paris.

The term “morgue” actually originated in 16th century France, where bodies were “morgued,” or scrutinized disdainfully by jailers before imprisonment. Initially, corpses were kept at the Châtelet prison, where they were displayed for identification through a window. Sounds simple right? Unfortunately no!

In 1868, a new morgue opened behind Notre-Dame, designed as a public exhibition space where bodies were displayed on slanted marble tables behind glass. Up to 40,000 people visited daily, including tourists, workers, and even murderers. At a time, 50 would crowd around large windows to gawk and gossip about the dead bodies. The morgue was a mix of curiosity and macabre entertainment, reflecting Paris’s evolving social scene. As the morgue was not refrigerated until 1882, cold water would drip from the ceiling constantly, giving the skin of the dead a bloated and puffy appearance. The dead would usually have to be removed after three days due to decomposition, at which point a photograph or a wax cast would take their place. The morgue operated as a spectacle until 1907, when it closed to the public for moral reasons.

L’Inconnue de la Seine: A Mysterious Icon

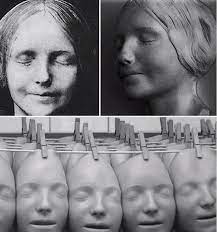

Notably, the morgue housed the body of L’Inconnue de la Seine, a young woman who was reportedly fished out of the Seine in the 1880s after a successful suicide attempt.

Arriving at the morgue with a ‘Mona Lisa’ smile on her face, an assistant was so taken with her beauty that a cast was taken of her face. Rather than drift into obscurity, that cast spurred a fascination that peaked in the 1920s and 1930s, with many households owning the death mask. In the 1960s her allure continued when she inspired the face of the first CPR dummy, Resusci Anne.

Since we are talking about CPR dummy, it makes sense to mention the hospital Hôtel-Dieu. Not only is it the oldest hospital in Paris, but it is also the oldest in the world. Founded in 651 AD by Saint Landry as a refugee for the poor and the sick, it has transformed over the centuries. The current Roman-inspired structure, built in the 19th century, replaced the original Gothic building destroyed by fire in 1772.

Grave Matters: Cimetière des Innocents

Exploring the darker aspects of Paris, we encounter the Cimetière des Innocents, or Saint Innocents’ Cemetery. This cemetery played a vital role in the daily life of Parisians, containing a church, mass graves, a fountain, and two reclusoirs—small cells where recluses were immured. For almost a millennium, it served as the burial ground for approximately two million Parisians which included individuals from 22 parishes, victims of the Black Death, patients from Hôtel-Dieu hospital, and unidentified bodies from the Seine or public streets. Initially comprising individual sepulchers, it later transformed into a site for mass graves, each pit capable of holding about 1,500 bodies, with new pits being opened only when the previous ones were filled.

By 18th century, the cemetery had become dangerously overcrowded and unhealthy, with the ground level rising 2.5 meters above surrounding streets. A pivotal event in 1780—when a partition gave way, spilling corpses into a nearby restaurant’s cellar—led to its closure. By 1786, the remaining bodies were moved to the Catacombs of Paris. Today, only the Fontaine des Innocents, originally part of the cemetery, still stands as a testament to this grim chapter in Paris’s history.

Parisian Chronicles: A Tale of Hidden Gems

A Tale of Traffic

Paris has a rich history of social unrest and power struggles, notably during the Middle Ages, religious wars, and the revolutions of 1789, 1830, and 1848. The urban landscape, chaotic and driven by economic interests, grappled with rising health issues and crime rates. A prime example of this chaos would be the tragic fate of King Henri IV who was assassinated in broad daylight by François Ravaillac in Paris’s bustling Les Halles neighborhood, while his coach was stuck in traffic. Henri IV’s father-in-law had unsuccessfully attempted to widen the narrow street in this busy marketplace area back in 1554. If he had succeeded, the traffic jam that aided Ravaillac’s attack might have been avoided. Ravaillac was captured, tortured, and executed by being drawn and quartered at Place de Grève in front of L’Hôtel de Ville. Henri IV, also known as le bon Roi or “good king,” left his mark on Paris, but his untimely demise is marked by a simple stone on Rue de la Ferronnerie, that reads:

“Henri IV, XIV Mai MDCX”

(Henri IV, May 14, 1610)

Haussmann’s Transformation

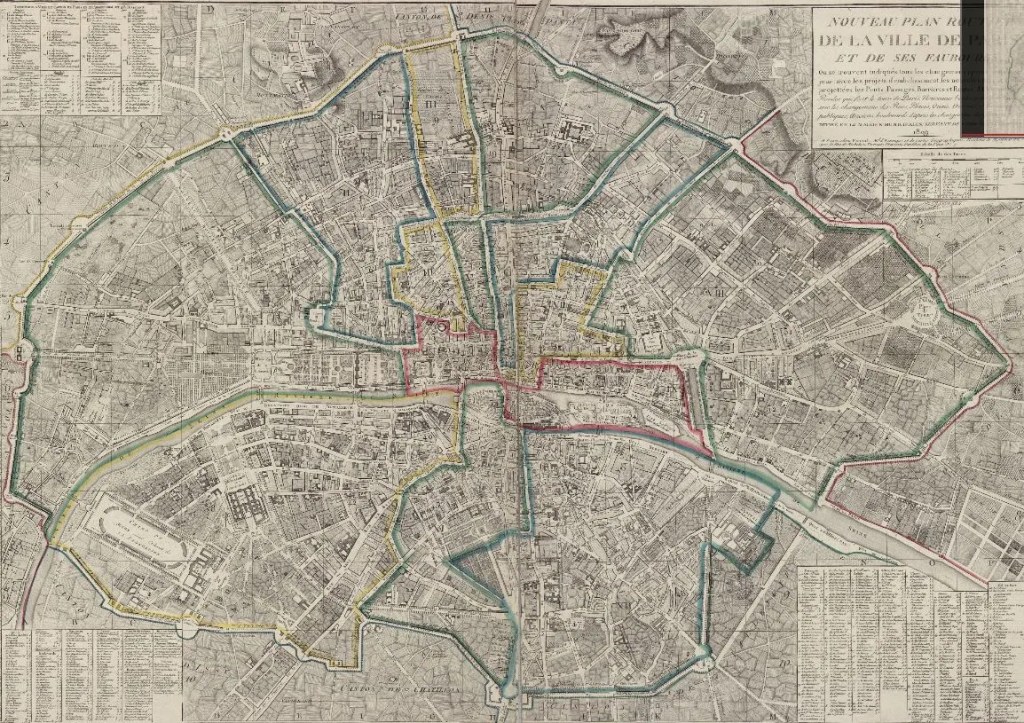

Napoleon III had big dreams for Paris, wanting it to be a stunning symbol of power and order. To make this happen, he brought in Georges-Eugène Haussmann in 1853. Haussmann’s task was monumental: to modernize and beautify Paris while addressing health concerns and improving infrastructure. Together with Napoleon III, Haussmann envisioned wide avenues that would facilitate troop movement and police control during uprisings. His first move was adding more land to Paris by joining nearby towns, making the city 40% bigger. Then, he split Paris into 20 sections, changing how the city was run and making old neighborhoods less strong.

The 20 arrondissements of Paris, established on January 1st, 1860, form a spiral starting from the city’s center and expanding outward like a snail, or “escargot.” Before this, Paris had only 12 arrondissements and was smaller in size. The symmetry of this arrangement likely led to its nickname ‘Le 75,’ as it corresponds to Paris’s postcode. All Paris postcodes start with 75000, so the 1st arrondissement would be 75001, while the 20th would be 75020.

But why the spiral shape? When the well-off residents of Passy and Auteuil learned they would be part of the new city, they were unhappy to find themselves in a new 13th district. It wasn’t because of superstitions about the number 13, but rather a saying, “se marier à la mairie du 13e” (getting married in the 13th), which meant living together without marriage when there were only 12 districts. To avoid this association, the mayor of Passy suggested the spiral layout. The idea caught on, and the number 13 was given to a less affluent southeastern area, preserving the dignity of the western neighborhoods.

Haussmann’s vision unified Paris with wide, accessible avenues, grand boulevards radiating from five major train stations, and consistent architectural styles, giving the city much of its modern charm and character. He also expanded the sewer network and developed a drinking water supply system, resulting in numerous public fountains. But his restructuring had another interesting consequence, that will speak about soon.

Rues of Paris: Portals to History

There are 6,100 rues – or streets – in Paris; the shortest one, Rue des Degrés, is just 5.75 metres long and can be found in the 2nd arrondissement. Rue Portalis, is a street named after Jean-Etienne-Marie Portalis (1746-1807), a prominent French lawyer and politician, who played a pivotal role in shaping the Napoleonic Code, the foundation of the French legal system.

As one of the chief draftsmen, Portalis penned key articles on marriage and property succession, infusing the code with the principles of Roman law. Enacted on March 21, 1804, the Napoleonic Code remains a cornerstone of French law and has profoundly influenced the civil codes of many countries in Europe and Latin America.

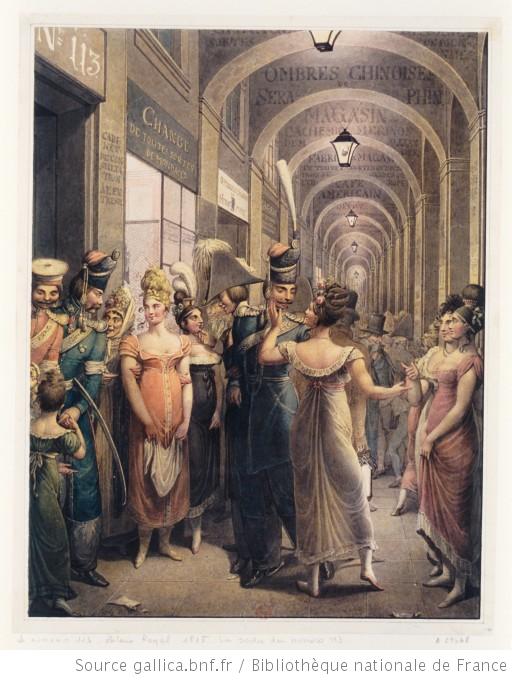

Ville d’Amour or Sex in the City?

In the Paris of the Third Empire, marital relationships were not centered on carnal desire. Husbands often sought pleasure elsewhere, frequenting prostitutes known as ‘asphalteuses,’ ‘lorettes,’ and ‘pierreuses.’ There was a distinct separation between respectable wives, who were treated like dolls, and prostitutes, who were seen as sources of sexual pleasure. Haussmann’s redevelopment displaced many prostitutes, who moved to the newly created boulevards. Cafes and restaurants doubled as places for culinary tourism and prostitution.

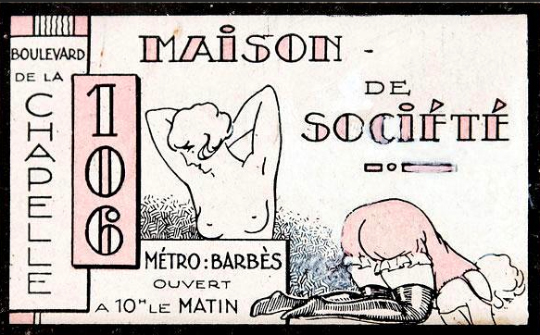

The influx of single migrants, soldiers, students, and workers, attracted by Haussmann’s public works projects, further fueled the demand for prostitution. This high demand for “love” contributed to Paris’s reputation as the “City of Love.” Prominent brothels, known as “maisons closes,” included Le Chabanais, La Fleur Blanche, and L’Étoile de Kléber. These establishments catered to various clientele, from the affluent to the masses and the clergy, with some brothels servicing up to 100 clients a day. I wonder if this is how the term French Disease for STIs came into existence!

During major events like the World Fairs, Paris became a hub for sex tourism, earning the moniker “the brothel of Europe.” In 1878, there were 2,650 registered prostitutes in Paris, a number that grew to 6,000 by 1900. This period also saw the emergence of “prostitution guidebooks” for men, detailing places of pleasure in multiple languages. The French openness towards sex and sensuality, along with public displays of both, set them apart from more conservative societies such as the Victorian England. This unrestrained attitude contributed to the term “French kiss,” denoting passionate and adventurous kissing practices. In 2013, the term ‘galocher,’ meaning to kiss with tongues, was officially added to the Petit Robert French dictionary.

Movies have had a significant impact on Paris’s romantic image. As a fan of chick flicks, one can’t help but hold high expectations after recalling the romantic scenes from “Before Sunset” and “One Day”. However, films like “Inception” and “The Da Vinci Code” also offer a different perspective on Paris in my vivid imagination.

In 2006, the Italian film “Ho Voglio di Te” (“I Want You”) featured a scene where two lovers write their names on a lock, attach it to Rome’s Ponte Milvo bridge, and throw the key into the river. While Ponte Milvo did not gain much attention, Paris’s Pont des Arts did.

By 2015, an estimated 700,000 padlocks, weighing as much as 20 elephants, adorned the bridge, causing part of it to collapse. Today, smaller segments of these love locks can be found throughout Paris. This particular section was located in front of Sacre Coeur.

Unfortunately for the City of Love, it’s not always a happy ending. Pont de l’Alma is also known for a tragedy – the 1997 car accident that claimed Princess Diana’s life in the tunnel between the bridge and Place de l’Alma. Near the site stands a replica of the Statue of Liberty’s flame, donated by the American newspaper Herald Tribune in 1897 to commemorate Franco-American friendship. This monument has become a place where admirers of Princess Diana come to pay their respects daily.

Glamour of Third Empire

Haussmann’s renovation included the creation of Avenue de l’Opéra, a direct route from the emperor’s residence to the opera house, with no trees to obstruct the view. This grand avenue enhances the Palais Garnier’s majesty, reinforcing its palace-like appearance.

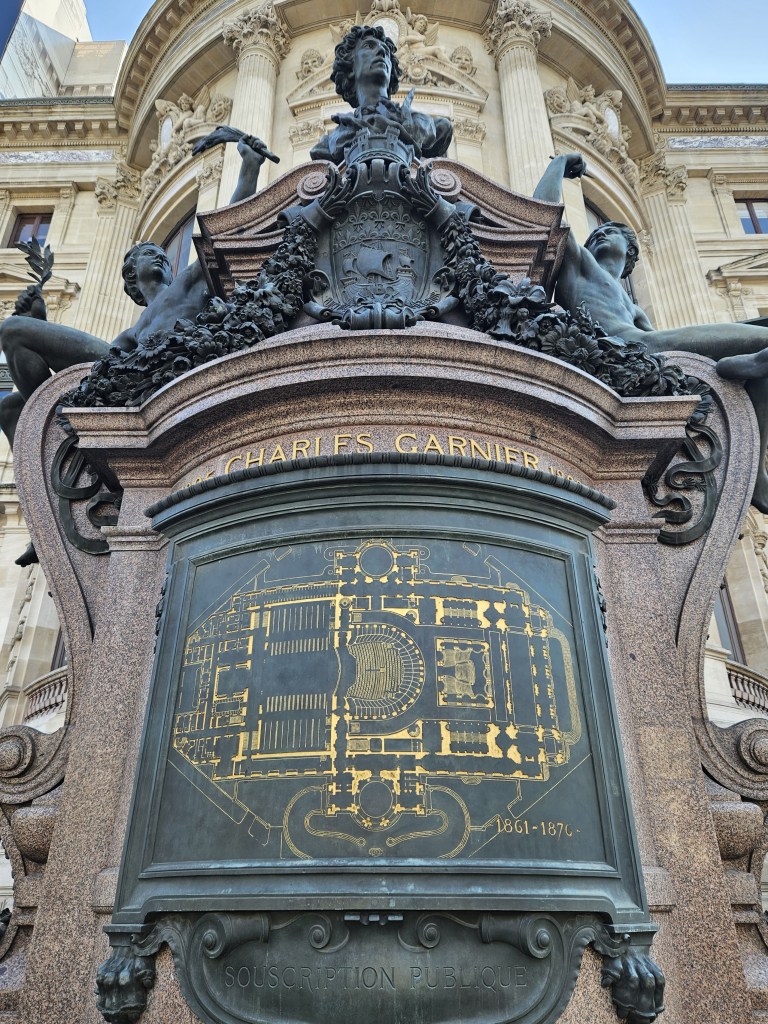

In 1858, Emperor Napoleon III and his wife experienced a failed assassination attempt at the Rue Le Peletier Opera House. This led to the decision to build a new, safer opera house. The project was entrusted to a then-unknown architect, Charles Garnier, who won a contest in 1860 to create an “imperial academy for music and dance.” Empress Eugénie was initially skeptical of his design, questioning its style, to which Garnier famously replied, “This is Napoleon III!” I guess it could be another reason why Palais Garnier has the signature of this unknown architect on its very walls.

Construction of the Palais Garnier began in 1861 but faced significant challenges, including a wet construction site that required a large cement reservoir to manage excess water. The project continued despite interruptions, including the Prussian War, during which the unfinished building served as a storage camp. The building’s main façade was completed in 1867, and the entire opera house opened to the public in 1875, costing over 20 million gold francs, making it the most expensive building of its time.

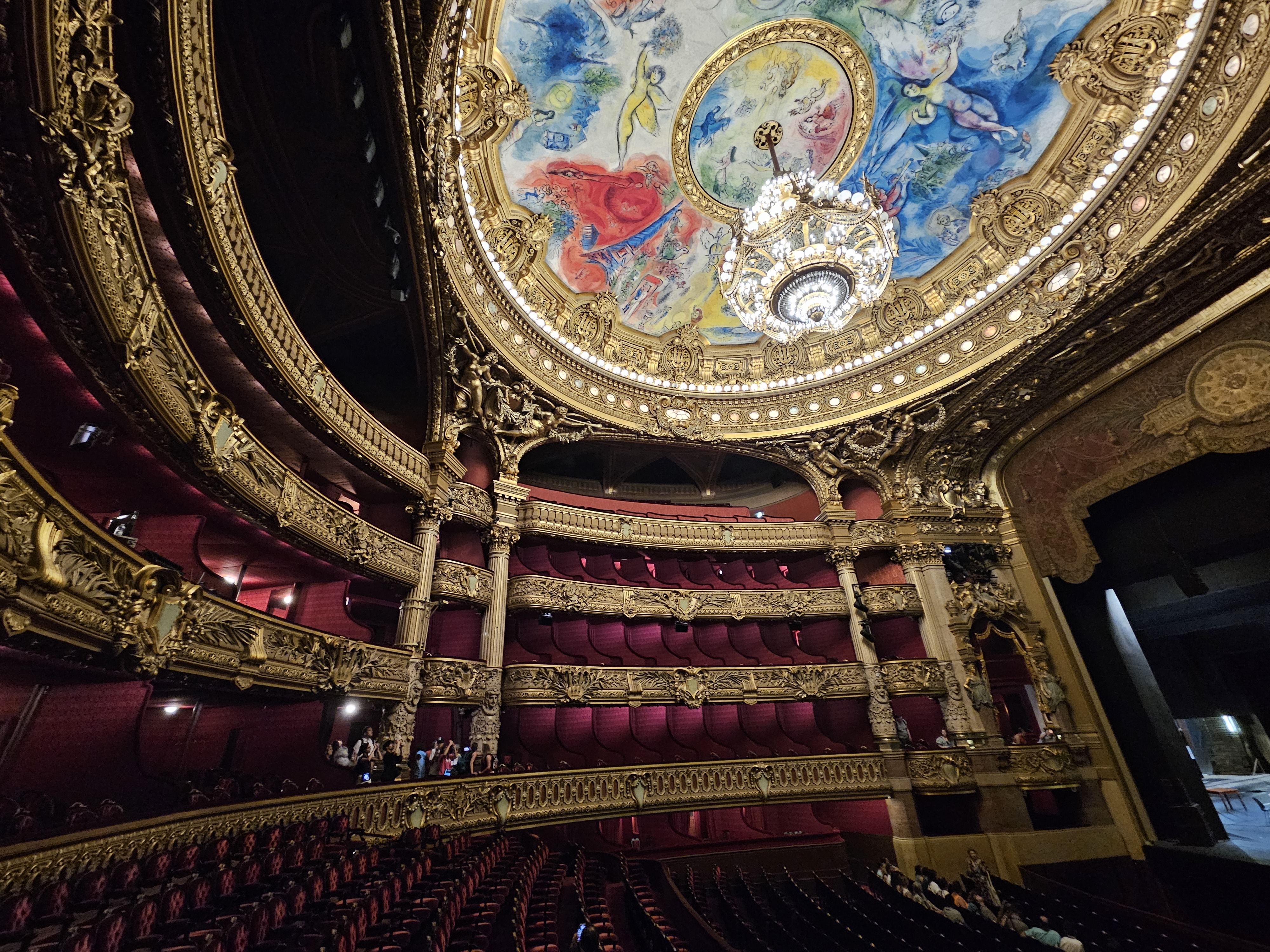

Renowned for its Neo-Baroque architecture and lavish decorations including 30 types of marble from various countries, Garnier’s design incorporated elements of a princely palace, hence the name “Palais Garnier.” The building also made history by installing a small power plant in 1883, making it the first opera house to use electricity, with lighting provided by bulbs from Thomas Edison.

The Opera Garnier was not just about music but also a show of class! Season ticket holders went to the opera 2-3 times a week, not because there were different performances or were opera fans, but to show off and socialize!The Grand Escalier, a triumphal entrance, surrounded by balconies over four floors, allowed guests to see and be seen, with shallow steps designed to reveal just a glimpse of women’s ankles.

The Emperor’s box in the Auditorium, prominently placed to the left of the stage, was designed for visibility rather than optimal viewing or acoustics. During the show, the lights remained lit in order to facilitate the popular activity of people-watching.

Finally, the Grand Foyer, inspired by Versailles’ Hall of Mirrors, was designed for spectators to socialize during intermissions.

One of the most striking features of the opera house is its 7-ton chandelier, designed by Garnier himself. Though magnificent, it was unpopular with some as it obstructed views. Tragically, in 1896, the chandelier’s counterweight burst through the ceiling during a performance, killing a member of the audience.

This incident inspired Gaston Leroux’s novel, “The Phantom of the Opera,” which also drew on other elements of the opera house’s history such as the Phantom’s box number 5. In Leroux’s novel, a myth about phonographic recordings buried in the opera’s cellars is mentioned. In 1907, the Gramophone Company indeed sealed 48 records in the cellars, opened 100 years later and digitized by EMI Classics as “Les Urnes de l’Opéra.” No corpse was found, contrary to the novel’s lore.

Parisian Woes

In the harsh winter of 1870-71, during the Franco-Prussian War, German troops besieged Paris, cutting off all food supplies. With no other options, residents resorted to eating horses, cats, dogs, and even zoo animals. By the end of May, reportedly, there wasn’t a single rat left in the city. After five months, Paris surrendered, but the aftermath brought the Commune uprising which resulted in death of almost 30,000 people.The Catholics took it as a sign from God. The Sacred Heart monument was built as a representation of national penance for the supposed excesses of the Commune de Paris of 1871, and of the conservative moral order.

The Basilica of the Sacred Heart (Sacre Coeur), designed by Paul Abadie, was constructed from 1875 to 1914 and officially completed in 1923. Its eclectic architectural style draws inspiration from Romanesque and Byzantine architecture, as well as the Saint-Front de Périgueux Cathedral. The façade features prominent equestrian statues of Joan of Arc and King Louis on horseback, with stone from Chateau-Landon used, similar to the Alexandre III bridge and the Arc de Triomphe. When rainwater comes into contact with the stone, it undergoes a chemical reaction, forming cullet, a thin white protective layer that naturally hardens in the sun.

It boasts of two records. First, the largest bell in France, called la Savoyarde, is inside the Basilica and measures 3 meters in diameter, 9.60 meters in outer circumference and weighs 18,835 kg. It dates back to 1895 and was built in Annecy in the French Alps. Its installation required a team of 28 horses. The basilica’s dome is the highest point in Paris after the Eiffel Tower. However, showstopper is the huge mosaic of Jesus Christ located above the altar. It is among the largest mosaics in the world (measuring 475 square meters) and was finished in 1922.

Rats, De Gaulle, and Pestilence

Interestingly, 1872 saw the return of rats to Paris. During the 14th century’s Black Death, flea-infested rats had caused a plague that killed about half the city’s population. In the 1871 siege, starving Parisians turned to eating rats, making rat paté a temporary delicacy. Once food supplies resumed, Parisians reverted to their regular diets, and the rat population around Les Halles surged again due to market waste.

During De Gaulle’s presidency, the relocation of Les Halles market deprived rats of their food source, causing them to invade nearby apartments. This led to a massive extermination campaign led by Julien Aurouze, a dedicated rat exterminator. From the Palais de l’Elysée, De Gaulle noticed a sign reading “ATTILA, Fléau des Rats” (Attila, Scourge of Rats), which he took as a personal affront. Despite his efforts, the sign and the exterminator’s business remained long after his presidency.

Founded in 1872, Maison Aurouze specializes in pest control and famously displayed mummified rats. The shop’s history highlights Paris’s ongoing struggle with these pests, a quirky yet significant aspect of city life.

Urban Flooding Tales: The Watchman and Other Untold Stories

Historic postcards capture the flooded City of Light in grainy black and white, depicting Parisians navigating the streets in wooden boats or along submerged sidewalks. The scenes, almost romantic in nature, evoke comparisons to Venice. However, these images don’t reveal the harsh reality faced by most Parisians during the ‘flood of the century’.

The city grappled with the loss of electricity, gas lighting, heating, public transportation, communication, postal services, clean water, trash collection, and food provisions. Once a symbol of modernity, Paris found itself plunged into a medieval-like existence. At the peak of the flooding, 300 streets were submerged, and 20,000 homes flooded, despite efforts to erect sandbag barriers or brick up cellar entrances.

The Rue Des Chantres is a narrow passageway with a dark history rivaling its haunted neighbors. In the early 1900s, an old hotel on this street served as a quarantine for sick children during a time when tuberculosis swept through Europe. To prevent the spread of illness, these children were locked away in the hotel’s lower floors, hidden from the public eye. Tragedy struck during a great storm that caused the Seine River to flood its banks. The Rue Des Chantres, located near the river, was completely flooded.

The floodwaters breached the old hotel, trapping and drowning the quarantined children inside. As we listened to the stories, a mark on the wall just below the street name oddly resembled a child standing there and watching. Locals often believe that the spirits of these children linger on the Rue Des Chantres. Visitors frequently report hearing eerie sounds of children whispering and playing, serving as a somber reminder of the young lives lost in this passageway.

Etched into stone or displayed on green plaques, these flood markers offer a hidden glimpse into the city’s history, often unnoticed by passersby. They signify the level reached by the Seine during the famous 1910.

City dwellers have relied on one particular figure to warn them of rising water levels—the Zouave. This stone statue, created by French artist Georges Diebolt in 1856, has served as an informal flood marker since its installation on the Pont de l’Alma. The bridge, commemorating a Crimean War victory involving Zouave soldiers, originally featured four statues representing different infantrymen. Over time, the other statues were relocated, leaving only the Zouave. Standing at 5.2 meters tall and weighing eight tons, the Zouave plays a crucial role during floods, with water covering his feet indicating alert conditions in Paris. The statue’s significance grew during the Great Flood, when images of him submerged up to his waist became iconic.

Through the years, he became a cultural icon of Paris, featured in dozens of songs and novels, including the Tintin tales, beloved by children of all ages. Although in The Adventures of Tintin, Captain Haddock uses the term “faire le Zouave” as an insult meaning “to act the fool.” The Zouave’s attire reflects North African styles of the early 1800s, depicted in paintings by artists like Van Gogh. The statue’s influence even extends to fashion, with “Pantalone alla Zuava” referring to short trousers inspired by the Zouave’s uniform.

Forged by Legends: Notre Dame

“The Hunchback of Notre Dame” film, serves as a familiar reference point for many outside France when it comes to the iconic cathedral. Inspired by Victor Hugo’s 1831 novel “Notre-Dame de Paris,” this Disney film sheds light on the cathedral’s historical context. At the time of the book’s release, Notre Dame was in a state of neglect, with damaged artwork, decapitated statues mistaken for French kings during the Revolution, and blackened stone from industrial pollution. Hugo’s love for medieval architecture motivated him to write about Quasimodo, Esmeralda, and Frollo, aiming to highlight the cathedral’s deterioration.

The novel’s success led King Louis Philippe to allocate over 2 million francs for its restoration. Architect Eugène Viollet-le-Duc led the 20-year project, costing 12 million francs, and added notable features like the 180-foot spire and famous gargoyles. Despite facing significant criticism, the restoration became iconic. Afterall, it cannot be denied that Notre-Dame, a symbol of French history and culture, has endured wars, revolutions, and natural disasters. Significant events, such as the crowning of Henry VI of England as King of France in 1431 and Napoleon Bonaparte’s coronation as Emperor in 1804, have taken place within its walls.

No legend can truly become L-E-G-E-N-D-A-R-Y unless there are ghost stories and other myths shadowing it. Two unknown women are frequently mentioned as ghosts, seen walking across Gothic architecture and gargoyles before vanishing . Rumors suggest they might have committed suicide by jumping from the cathedral’s roof.

During the construction of Notre Dame, the aim was to create the finest cathedral in Europe. Among the craftsmen was a Frenchman named Biscornet, who faced numerous rejections. And yet, at the time of unveiling, the finished cathedral door showcased intricate ironwork that was unprecedented, elegant, and perfect. A fact that even modern metal experts can’t explain how the ironwork was achieved with medieval tools.

However, in the superstitious 1300s, the craftsmanship seemed too extraordinary to be human. Rumors spread that Biscornet had sold his soul to the devil for this masterwork. When the doors were installed, they wouldn’t open, and Biscornet was found in his studio unconscious with the project mysteriously completed in record time. Priests claimed the locks only worked after being sprinkled with holy water, fanning the flames of suspicion. Despite insisting he was the sole artist, Biscornet couldn’t shake the unholy accusations. He died soon after, reinforcing the belief that the devil had returned for his soul. Interestingly, the name Biscornet can be broken down into “bis” (two) and “cornet” (horn) in French, hinting at “the two-horned one.” Nevertheless, rumors are afloat that homage to Satan appears hidden within the doors’ design. Close inspection of the irons swirls on the door reveals swirls similar to the number 666. I guess that’s the main reason why the door is known as the Devil’s Door.

The 2019 fire caused significant damage, particularly to the roof and spire. And guess who comes to the rescue? Virtual reality! Assassin’s Creed Unity, a popular action-adventure video game developed by Ubisoft Montreal and released in 2014, is set in Paris during the French Revolution and features stunning recreations of iconic landmarks, including the Notre-Dame cathedral. Ubisoft’s 3D model, created for Assassin’s Creed Unity, is highly detailed and accurate, based on historical records, architectural plans, and photographs of the cathedral as it was after its renovation in the mid-1800s. After the fire, Ubisoft donated €500,000 for restoration efforts and provided its detailed 3D model of the cathedral to aid architects and engineers.

Cafés to Carnage: Affairs of Chanoinesse

Strolling along rue Chanoinesse today, you’ll find a charming street with views of Notre Dame Cathedral and one of the city’s loveliest café bistros, Au Vieux Paris d’Arcole. The cafe is as old as its name suggests! Constructed in 1512, around the same time Notre Dame cathedral was completed, the building was once home to the Canon of the nearby cathedral.

By the 18th century, it had been purchased by a private citizen and was turned into a wine bar. It has remained a place for Parisians to congregate to eat and drink ever since. However, this picturesque setting belies a darker history.

Perhaps rather macabrely, the café is situated right next to a courtyard which is paved with repurposed gravestones, which were taken from a nearby church after it was pulled down in the 18th Century.

The street was once notorious for the Affaire de la rue des Marmousets, also known as the Affaire de la rue Chanoinesse after a later name change.

The Pie Killers

French cuisine is a high point for many tourists, which includes me as well! But I never expected to come across a darker fate of one of the most sought-after culinary delights! Lets meet the Pie Killers of Paris, a tale quite similar to Sweeney Todd, the fictional London barber who slit his customers’ throats then gave the bodies to his lover to be cooked into pies and sold in her pie shop.

In medieval Paris, meat was a luxury. Between 1384 and 1387, the butcher on rue des Marmousets became infamous for his delectable meat pies, renowned throughout France. However, for some, these pies were literally “to die for.” The meat had a delicate flavour, quite unlike anything they had experienced before, and even King Charles VI was said to be a fan.

The story goes that during the 14th century, a barber and a pastry chef on rue des Marmousets entered into a horrific pact. Students from the nearby Chapter of Notre-Dame began to disappear, often foreign students with no local ties. The barber would kidnap and butcher these unfortunate souls, passing their remains through a trap-door into the pastry shop’s cellar, where the chef turned them into meat pies. This gruesome practice allegedly continued for years until a faithful dog exposed the crime.

A German student named Alaric, one of the victims, had a loyal dog that wouldn’t stop barking outside the barber’s shop. This drew the constabulary’s attention. Upon inspection, they discovered the macabre truth of the killing duo.

Unfortunately while the duo were rumored to have killed over 2000 young men, they were found guilty for only 4. For their heinous crimes, the butcher and pastry chef were burned alive, and their shops were destroyed. Today, the location believed to be the site of these gruesome murders is, ironically now the headquarters of a Paris Police Department.

The French Bread Law

After the freaky duo, there is a much need for some Parisian breads. But did you know according to the French Bread Law, a traditional Parisian baguettes have to be made on the premises they’re sold and can only be made with four ingredients: wheat flour, water, salt and yeast. They can’t be frozen at any stage or contain additives or preservatives, which also means they go stale within 24 hours.

To be called a boulangerie, a French bakery has to make its bread on the premises. If this prized word doesn’t feature in the name of the bakery or isn’t plastered on the window it could be a plain old dépôt de pain selling industrially-made bread. Each year, a bakery in Paris receives an award for crafting the best baguette in the city. The winner gets the honor of delivering fresh baguettes to the French President at the Élysée Palace for an entire year.

As per the Parisian norm, croissant and coffee go hand-in-hand. I don’t know about everybody, but it is definitely the impression I gathered after going through all the viral Instagram reels. Historians will agree with me – The Parisian café evolved from a place for alcohol consumption to a social institution where revolutions were planned, and debates stirred.

Jean de Thévenot introduced coffee to Paris in 1657. Although an earlier account suggests coffee was sold under the name “cohove” or “cahoue” during Louis XIII’s reign, this lacks confirmation.

Coffee officially became popular after a 1670 visit from an Ottoman delegation to King Louis XIV’s court, introducing Turkish coffee to the French elite. This sparked a trend that led to the opening of numerous coffee houses. By 1720, Paris boasted nearly 300 cafés, growing to 1,000 by 1750 and almost 2,000 by the late 1700s. Cafés became hubs for artists and thinkers, fostering community, conversation, and creativity. Café Procope, established by Italian-born Francesco Procopio, stood out by offering patrons drinks in a luxurious setting, complete with porcelain cups, marble tables, gilded mirrors, and chandeliers. Located near the Comédie-Française theatre, it attracted famous patrons like Jean-Jacques Rousseau, Dennis Diderot, Voltaire, Benjamin Franklin, Thomas Jefferson, and Napoleon.

In other culinary news, France is famous for its love of escargot or snails. But did you know, every year, the French consume a whopping 25,000 tons of these little gastropods – that’s about 6.5 snails per person! This is roughly equivalent to the weight of 2.5 Eiffel Towers!

Chronicles of City of Light

A Tale of Twin sisters

Unlike other major capitals with numerous sister cities, Paris shares a unique and exclusive bond with only one city—Rome. While New York boasts 13 twin cities, including Madrid, London, and Cairo, Paris and Rome have chosen to embrace a singular partnership.

This special relationship was formalized in 1956 with a pact signed at the Hôtel de Ville, the City Hall of Paris. This agreement symbolizes the deep cultural and historical connections between the two cities. The mayors of Paris and Rome continue to honor this bond with regular visits, reinforcing their unique alliance. The sentiment behind their twinning is beautifully captured in the saying: “Only Paris is worthy of Rome; and only Rome is worthy of Paris.”

The City Hall has been the seat of council since 1977. The building facade features 338 individual statues of illustrious Parisians along with other sculptural elements and figures. Since I had to pay city tax separately beyond my accommodation charges, I was very interested in the building that was responsible for this impact on my finances.

A Bridge Beyond Numbers

The charming stone bridge that leads you to the City Hall, known as Pont Neuf, holds a fascinating secret. Despite its name, which means “New Bridge,” it has nothing to do with the number nine. Named by King Henry III in 1578, Pont Neuf was innovative for its time, being the first bridge in Paris without houses built upon it. With its modern design and paved surface, it quickly became a popular gathering spot for socializing. Today, Pont Neuf stands as the oldest surviving bridge in Paris, blending history and modernity to captivate visitors.

Ville-Lumière

Interestingly, the City of Light (Ville-Lumière) nickname has nothing to do with actual lights. It’s a fun Paris fact that even though the French capital was one of the first in the world to install street lighting, the nickname has nothing to do with electricity. It derives from the large number of bright intellectuals that lived in Paris through the years. Some of the most notable ones include Ernest Hemingway, F. Scott Fitzgerald, Gertrude Stein, T. S. Eliot, Claude Monet, Salvador Dali, Pablo Picasso, Claude Debussy, and Voltaire. In fact, the Montparnasse district in the 14th arrondissement was home to writers (like Hemingway) and artists in the 1920s and 30s.

La capitale de la création: The Capital of Creation

La Belle Époque

Referencing the period between 1871 to 1914, La Belle Époque literally means “the beautiful era” in French. Following the relentless building and rebuilding in the city, Paris during La Belle Époque played host to two iconic international expositions, the World’s Fair of 1889 and 1900 respectively. Many of the city’s landmarks such as Petit Palais and the Pont Alexandre III were built for these two fairs and have continued to dazzle locals and tourists alike to this day.

Petit Palais

Sparkling Eiffel

But perhaps the most remarkable of all was the Eiffel Tower, the beloved icon of the French capital. Nicknamed the Iron Lady, the Eiffel Tower was the highlight of the 1889 World’s Fair and was the world’s tallest structure, until the Chrysler building came in 1930. Nothing captures the essence of City of Light better than the sparkling Eiffel Tower. It was built in just two years by 132 workers and 50 engineers with a goal of showcasing France’s industrial prowess, and received 2 million visitors during the 1889 exhibition.

Initially criticized by Parisians, the Eiffel Tower was almost demolished in 1909 after its permit expired but was saved as a telecommunications tower. Standing at 324 meters (with antennas) and weighing 7,300 tons, the Eiffel Tower’s pressure on the ground is equivalent to a seated man on a chair. Today, it attracts 7 million visitors annually and remains a self-sustaining icon.

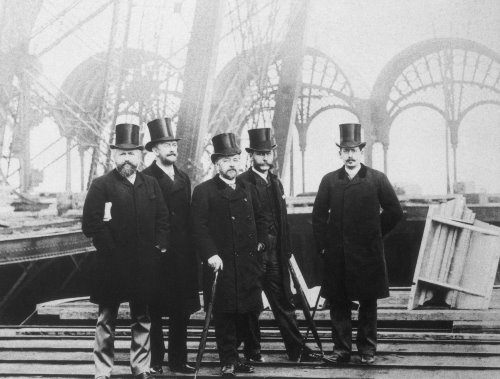

Gustave Eiffel’s construction company won the project, but the design of the Eiffel Tower wasn’t Gustave Eiffel’s idea but that of his engineers, Émile Nouguier and Maurice Koechlin. nspired by bridge piles the company built in Portugal and France, their proposal was selected among 107 projects for the 1889 Universal Exhibition.

The construction involved 18,000 parts and 2.5 million rivets, with workers moving 48,000 cubic meters of earth to build the foundations. The Eiffel Tower features a unique design with hydraulic jacks and innovative scaffolding. Gustave Eiffel celebrated with workers in 1888 by abolishing a salary deduction for accident insurance. The tower was inaugurated on March 31, 1889, with Eiffel planting the French flag at the summit. It is said that Gustave Eiffel also built a private apartment at the top of the Eiffel Tower, which was used for entertaining illustrious guests like Thomas Edison. Though not open to the public, visitors can catch a glimpse through a viewing window.

Paris Metro

Another key infrastructural breakthrough during La Belle Époque was the Parisian Métro, which is short for Métropolitain. Construction for this rapid transit system began in 1890, with established engineer Jean-Baptiste Berlier helming the overall design and planning. In operation since the turn of the 20th century, the Métro has been known for its unique entrances rich in Art Nouveau influences.

Art Nouveau

Much more than a staid school of 19th-century architecture, Art Nouveau was an entire aesthetic movement. From architecture and design to the decorative and fine arts, Art Nouveau, or “new art,” was everywhere. It was first introduced in Paris by French architect Hector Guimard, who drew inspiration from Belgian architect Victor Horta. Guimard’s signature metro entrances, with their glass roofs, railings, and ‘Métropolitain’ signs, are iconic. These entrances, in the ‘dragonfly’ style, exemplify the main principles of Art Nouveau: the use of metal, inspiration from flora and fauna, and fluid, curvilinear designs. Hôtel Deron-Levent and Hôtel Guimard are another examples of Art Nouveau designed by Hector Guimard. Another example would be the art nouveaux house located in Montmartre, that was once occupied by artist Maurice Neumomt (1868 – 1930).

And let’s not forget the most famous structure that exemplifies Art Nouveau – Galeries Lafayette Haussmann. The ceiling, designed in 1912, showcases the Art Nouveau style of that era, crafted by Édouard Schenck, Jacques Grüber, and Louis Majorelle.

In contrast, Art Deco (1910-1940) emerged as a reaction against Art Nouveau, favoring rectangular lines and stylized, almost flat floral elements.

Salon and Art Revolution

In the spirit of innovation and experimentation, La Belle Époque was also a time when art went through a great change. Prior to the 1870s, most artists remained conservative and adhered to the styles favored by the Académie des Beaux-Arts, an institute of patronage set up by Louis XIV in 1648 as a way of reinforcing his absolutist prowess. The annual Salon showed its preference of artworks that touched on traditional subject matter such as religious and historical topics.

However, a group of artists rebelled against these rigid interpretations, pioneering a new approach that featured non-realistic brushwork and everyday scenes. This group, known as the Impressionists, included now-famous artists like Claude Monet, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, and Camille Pissarro.

Their revolutionary work laid the groundwork for later movements such as Post-Impressionism and Fauvism. Montmartre, known for its vineyards since the Middle Ages, became a hub for famous artists like Renoir, Van Gogh, Lautrec, and Picasso, who immortalized Paris further.

Paul Cézanne (left; seen at Abu Dhabi Lourve); Vincent Van Gogh (top right; Immersive experience held in Mumbai in 2023) and his painting (bottom right, taken from Google)

Bistros to Ballrooms: Icons Unleashed

As the vibrant artistic community led a cultural revolution, urban leisure and mass entertainment also flourished. Music halls, cabarets, cafes, and salons emerged across society. And so did many legends.

For instance, the word bistro was invented at the Place du Tertre square’s oldest restaurant, La Mère Catherine, in 1814 during the Russian occupation after the Battle of Paris. The story goes that Russian soldiers would enjoy their alcoholic beverages there, but often shout “bystro!” (meaning “quick” in Russian) to hurry their comrades to finish drinking to rejoin the ranks.

One establishment that epitomized this vibrant lifestyle was the Moulin Rouge, a popular cabaret in Paris, founded in 1889 in Montmartre. Its iconic red windmill made it one of the world’s most recognizable structures. Interestingly, both Moulin Rouge and Eiffel Tower were unleashed on the French sensibilities in the year 1889. Unlike the sparkling status of the Eiffel today, Moulin Rouge was the first building to receive electricity. A hallmark of La Belle Époque, the Moulin Rouge is best remembered as the birthplace of the French Can-can, a lively dance featuring high kicks, splits, and cartwheels. In fact, the dance was accidentally invented while the girls were kicking the hyper-eager men.

The windmills in Montmartre were originally used to grind flour and press local grapes. In 1809, the Debray family bought these mills. During the siege of Paris in 1814, miller Debray heroically defended the windmill against the Cossacks and was killed, his body nailed to the windmill’s wings. By 1833, the last enterprising Debray brother opened an area for dancing, luring patrons with cheap wine and dancing. ‘Le Moulin de la Galette’ was named after a type of bread made from the Debrays’ flour and sold with local wine.

Capitale de la Mode

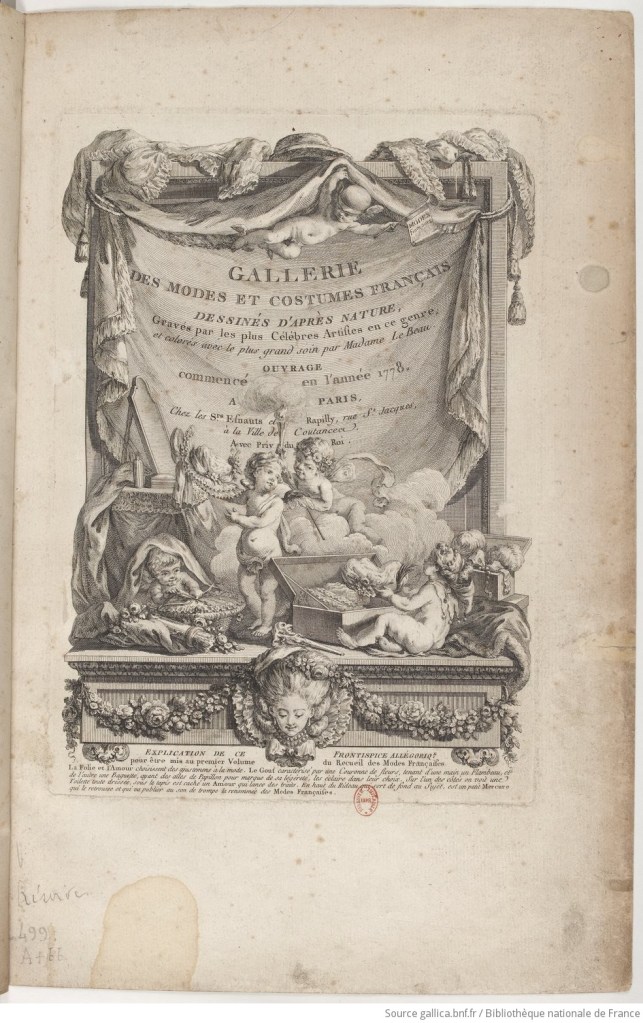

Fashion, at the nexus of art and consumerism, shapes and reflects our desires, bodies, and eras. At its heart lies Paris, a beacon of innovation and tradition in the fashion world. Fashion historian Valerie Steele encapsulates this allure in her book “Paris: Capital of Fashion,” where she remarks: “The history of Paris fashion blurs inextricably into myth and legend.”

Understanding Paris as the capital of Fashion requires grasping the essence of couture. Often misused worldwide to signify quality, the term holds a regulated, complex meaning, especially in France. Protected by law, its use is overseen by the Fédération Française de la Couture, akin to champagne’s strict criteria.

A couturier, a designer crafting bespoke garments, is distinguished by the French Chambre Syndicale de la Haute Couture. Ateliers within couture houses specialize in soft dressmaking (atelier flou) and tailoring (atelier tailleur), each mastering distinct skills.

To be recognized as haute couture, a fashion house must meet stringent criteria set by the Fédération Française which includes:

- Designing made-to-order pieces for private clients

- At least one fitting,

- Having an atelier in Paris that employs at least 15 full-time staff, and

- Presenting collections twice a year with a minimum of 50 original designs.

These standards ensure that haute couture remains an exclusive and high-quality segment of the fashion industry.

So why are we learning about these terms and terminologies?

Haute Couture trace back to an Englishman once famed but now largely forgotten by the mainstream. Charles Frederick Worth—regarded by many fashion historians as ‘the father of haute couture’ and ‘the first couturier’—established the first Couture House in Paris, thus championing exclusive luxury fashion for the upper-class woman.

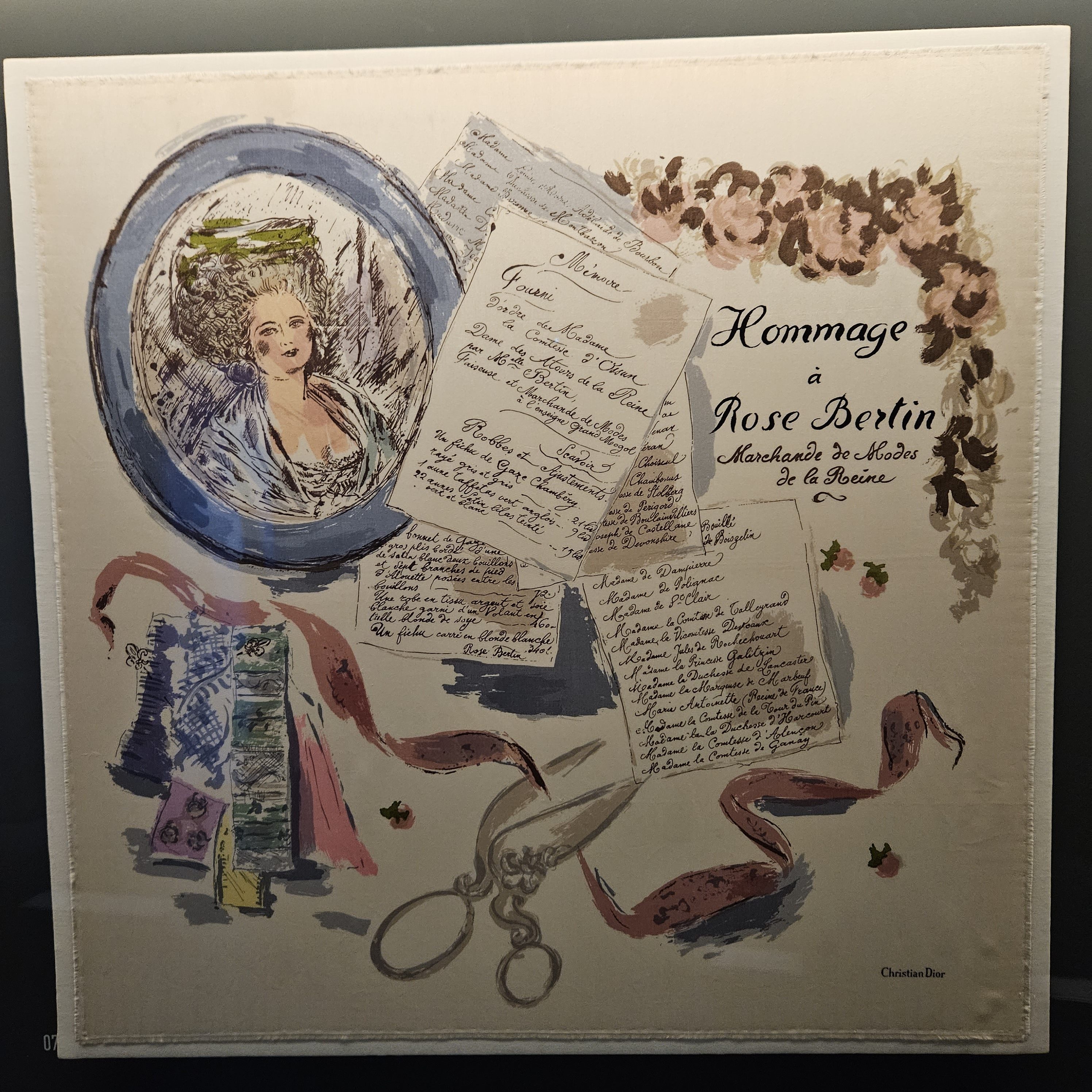

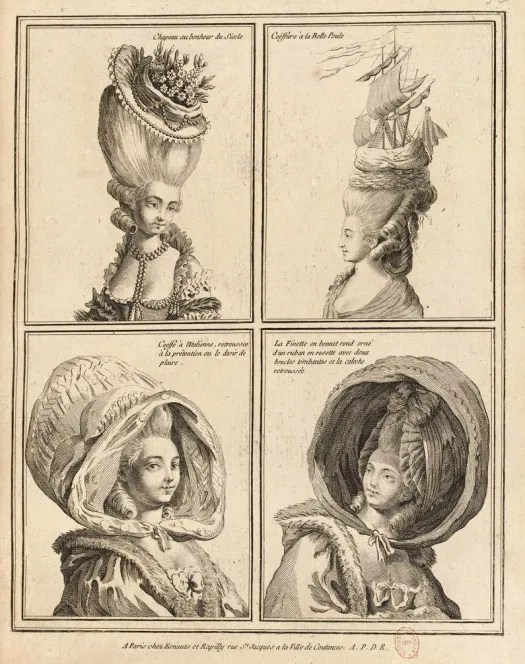

No one defines haute couture as Marie Antoinette who left behind a lasting style legacy. From Luxury aprons to iconic pouf stylings, she was on top of her game.

And it was all thanks to Rose Bertin, a milliner introduced to Marie Antoinette by the Duchess of Chartres, who later became a top designer in Paris. Known for her high charges and unique style, Bertin dressed the queen and others, breaking the norm of exclusive royal designers. This also prompted the thrifting trend among the wealthy, with Marie Antoinette’s hand-me-downs frequently worn or sold.

“Fashion is to France what gold mines are to the Spaniards.”

Jean-Baptiste Colbert, Louis XIV’s minister for finance and economic affairs, on the impact that fabrics had on French economy

While discussing his Queen, one cannot overlook the influence of our Sun King, Louis XIV. When he ascended the throne in 1643, Paris wasn’t the fashion capital—Madrid held that title. Spain’s flourishing Golden Age, supported by a vast global empire, boasted a rigid, predominantly black fashion symbolizing wealth and dignity. French aristocrats imported their fashion from Spain, tapestries from Brussels, lace and mirrors from Venice, and silk from Milan, as France did not produce luxury goods of comparable quality and lacked the clout to dictate fashions to other countries. Enter Louis XIV, the trendsetter!

Louis XIV, renowned for his opulence, became a trendsetter, sporting red-heeled shoes and extravagant wigs, prioritizing fashion to bolster the economy. Known for his love of opulence, Louis XIV famously wore red-heeled shoes and ostentatious wigs. Under his rule, trade guilds, known as corporations were established, to set industry standards and provide structure. Every profession, from tailors to dressmakers to fan makers, had its own union, which offered organization and power.

In a culture where the wealthy loved to flaunt their riches, Louis XIV implemented etiquette standards that required multiple costume changes throughout the day, further embedding fashion into French society.

Additionally, the emergence of the fashion press in the 1670s propelled French fashion to new heights, making concepts like seasonal trends and style evolution accessible to a wider audience. However, the French Revolution ushered in an anti-fashion movement, advocating simplicity and modesty in contrast to the opulence of the monarchy.

In 1800, a law was passed, making it illegal for women to wear trousers without police permission. The aim was to curb revolutionary women’s demands for equality in jobs and clothing. Although this law went unenforced for decades, France’s Minister of Women’s Rights Najat Vallaud-Belkacem officially repealed it on January 31, 2013, after 213 years.

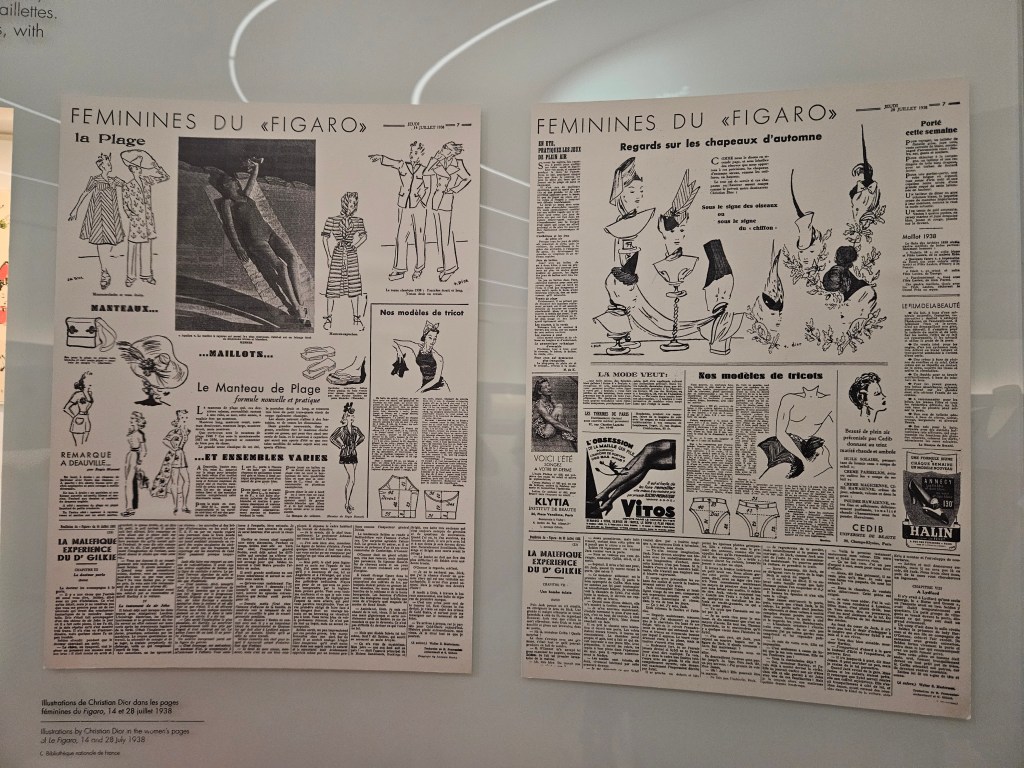

The late 19th and early 20th centuries saw the French fashion industry expand significantly, with haute couture, prêt-à-porter, and lingerie emerging as distinct styles. Haute couture, introduced as Paris vocabulary in 1908, featured leading couturiers like Jacques Doucet, Madeline Vionnet, Coco Chanel, and Elsa Schiaparelli.

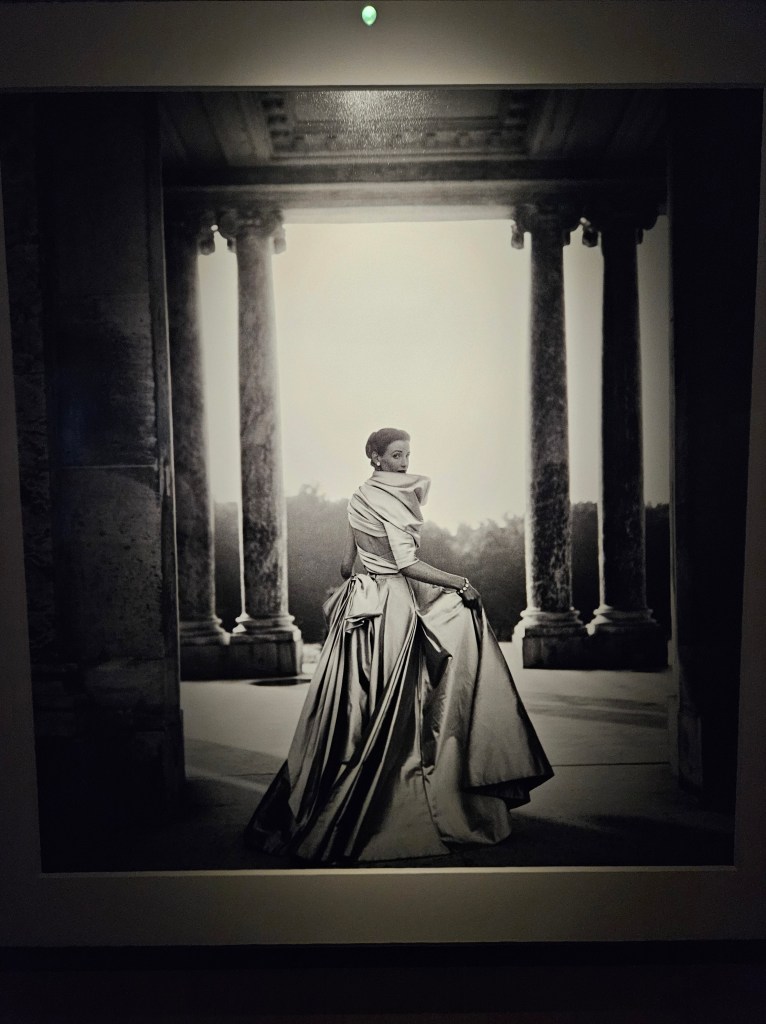

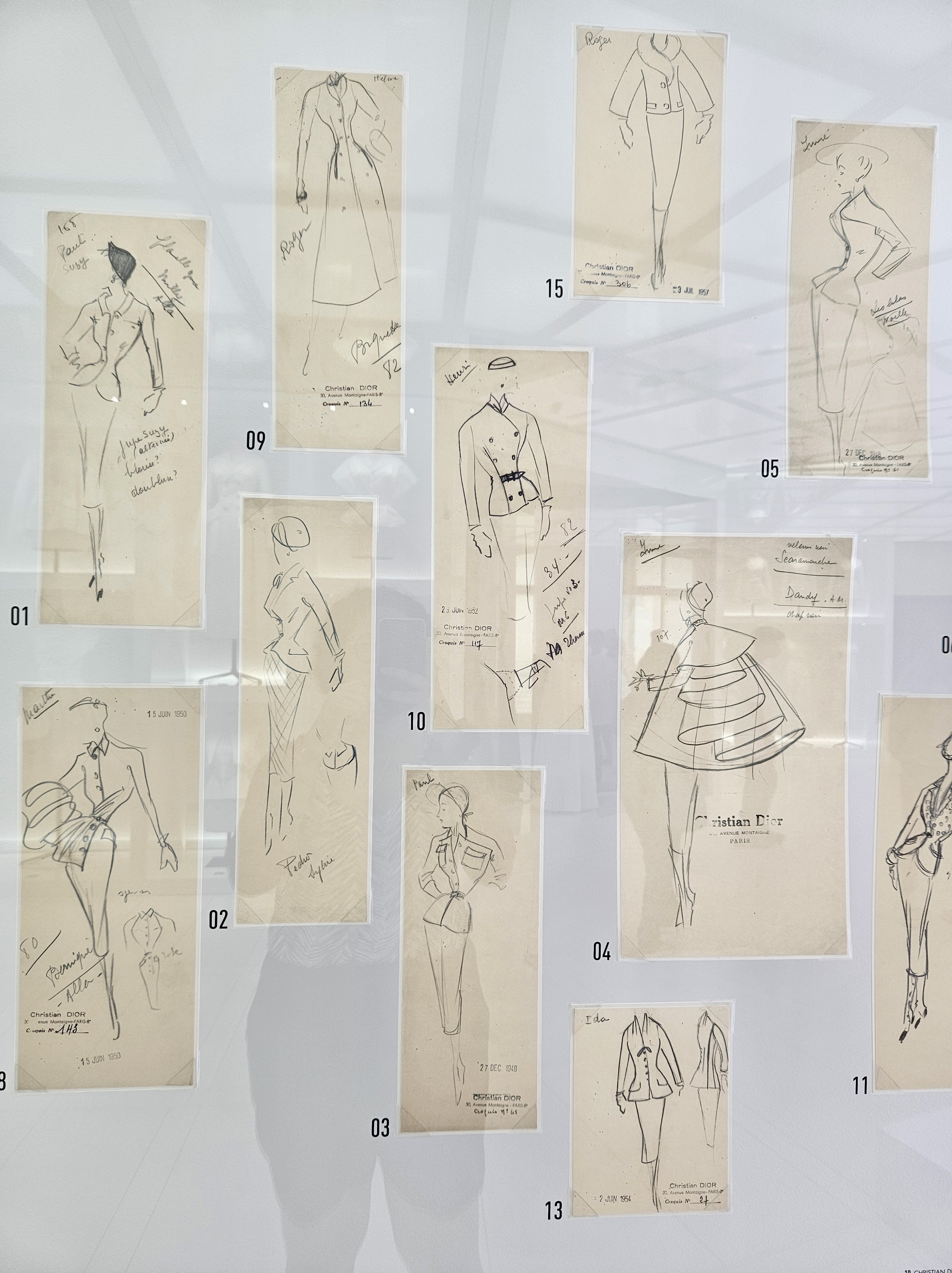

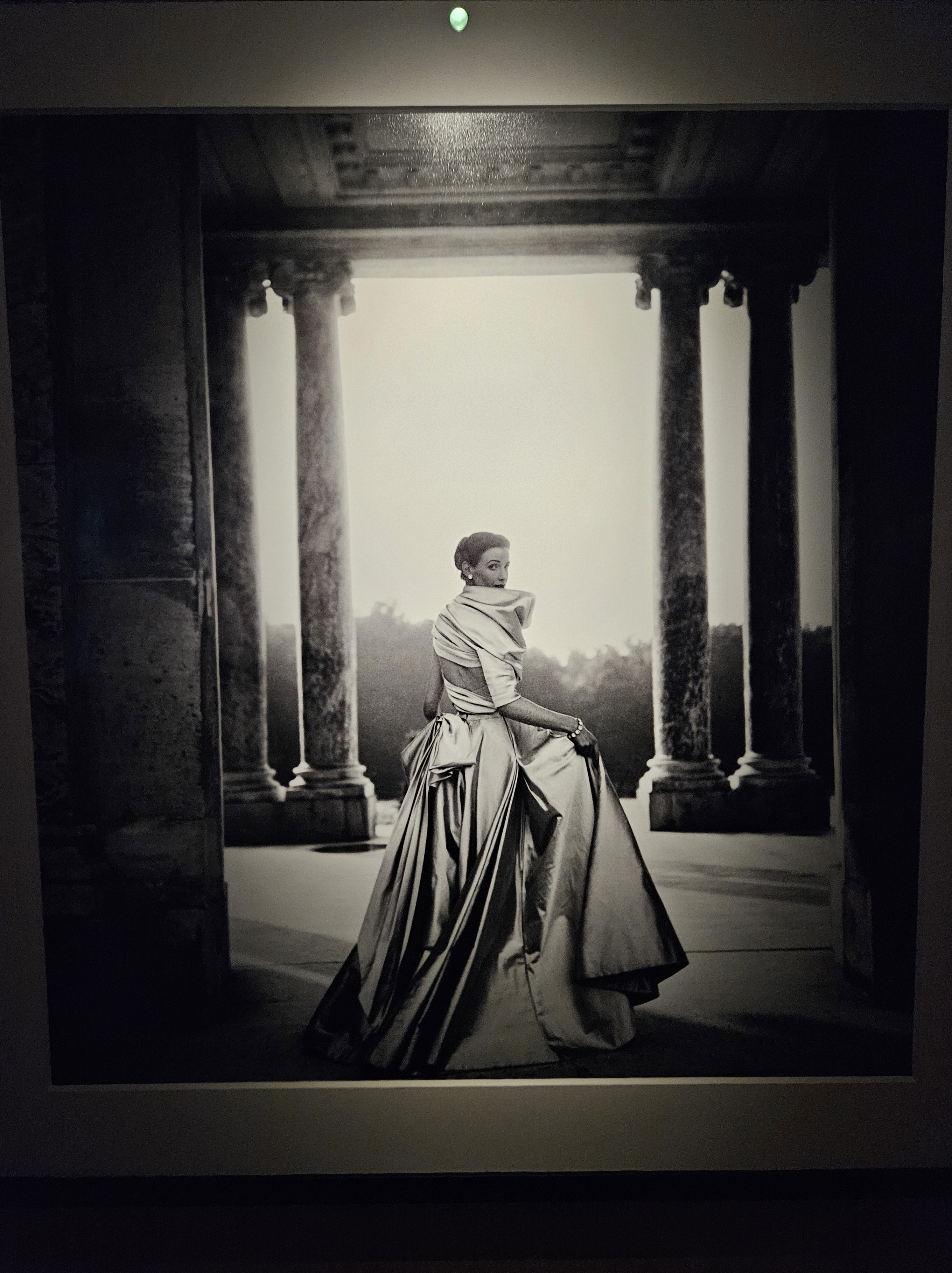

Post-World War II, Christian Dior’s “New Look” revolutionized fashion with exaggerated silhouettes and deliberate femininity, while Yves Saint Laurent popularized prêt-à-porter, that is. mass-produced clothing for everyday wear.

In 1921, L’Association de Protection des Industries Artistiques Saisonnières (PAIS) was founded to protect designers’ work from being copied and establish workforce regulations.

Paris Fashion Week, inaugurated in 1973, set the stage for iconic events like the Battle of Versailles Fashion Show, showcasing French and American designers. But in the world of style, is there ever a clear winner? Paris maintains its enduring influence, from denim jeans, born in the French city of Nîmes and popularized by Levi Strauss among Californian gold miners, to the bikini, a creation of French designers Jacques Heim and Louis Réard in 1946.

Even accessories tell stories of Parisian panache. The Panama hat, unveiled at the 1855 World’s Fair in Paris, remains a symbol of timeless elegance. Despite its association with the failed Panama Canal project, it still retains its charm, adorning heads at events like the French Open at Roland Garros.

The nickname “Paname” for Paris, once linked to a failed endeavor, remains a stylish emblem of the city’s enduring allure. And speaking of innovation, it was the French army that pioneered camouflage during World War I in 1915, forever changing the landscape of military attire. And let’s not overlook the beret! Originating from France, this chic headgear isn’t just for military uniforms—it’s a fashion statement beloved worldwide.

The Parisian way of life was truly a revelation, especially when you marry the beauty of the city with all the heard and unheard stories from the yesteryear!

Now the Pro tips:

I utilized the day pass called Mobilis, priced at around 7.20 Euros, valid for Zones 1 and 2 in Paris. With a pack of 10 tickets, I had the flexibility to explore the city at my own pace.

To combat jet lag, late check-in and maximize my time, I began my day early with a general city orientation, opting for a guided walk highlighting Paris’s main attractions.

I prefer to avoid crowded places and long queues, so I skipped the Eiffel Tower viewing gallery. I don’t see the point of paying for views that can be enjoyed for free. Instead, I took in a stunning city view, with the Eiffel Tower as part of the landscape, from the top of Galeries Lafayette. While exploring, I stumbled upon an interesting piece of memorabilia near a popular spot where tourists take photos with the Eiffel Tower. I believe this location is Pont d’Iéna, but I might be mistaken since I found it quite randomly.

For an enchanting view of the Sparkling Eiffel, I suggest visiting Pont de Bir-Hakeim. The bridge offers a free and iconic view, but be sure to check the timings beforehand, as they vary with daylight savings. This detail often goes unnoticed in the influencer era.

As for the Opera Garnier, I saved it for a special outing with my girlfriends. We all opted for an audio-guided tour to enhance our experience. As for the Dior Museum, booking tickets in advance is advisable due to queues. For a different perspective on Paris, I joined a Haunted and Crime Tour, exploring the city’s darker side. I’ve included the links for your reference. Don’t worry, I get no commission out of this!

Further Readings

- Paris Floods

- Fake Paris

- Paris’ Les Cemetery

- Charnel House

- La Belle Époque: Europe’s Golden Age

- Fashion History Timeline

- Fashion at Versailles

- Power and Pomp of a wig

- Paris Fashion

- How 100 Years Of Haute Couture Shapes The Runway At Paris Fashion Week

- Lola Gonzalez (2019, 24 January). When Paris was the Whorehouse of Europe. Social Worlds. Accessed on 5 June 2024 at https://doi.org/10.58079/u9c1

Recent (and not-so recent) Posts:

[…] is a Celebratory post. Hope you all like […]

LikeLike

[…] has a rich history, over 2,000 years old4. Exploring its hidden gems is like going back in time. You’ll see the city’s tourism […]

LikeLike

[…] business and creativity, innovation frequently begins as a hidden gem—an idea that seems small or unconventional at first. When nurtured, such ideas can develop into […]

LikeLike