The Ton season is upon us and what better way to honor it, than a post dedicated to one of the most historic artifact that can be linked to that era. Yes…I am indeed talking about the Bridgerton season that is back in action for May and June. And while we are all dividing ourselves into various camps: Kate-Anthony vs Colin-Penelope, let’s pause a bit to reflect on one of the most used Victorian accessories – Fans.

Whilst it seems reasonable that a Victorian lady could have used her fan not only as an accessory, but also as a tool to attract additional attention through affectionate gestures, it is perhaps doubtful that her male counterpart could have mastered this secret language, said to have consisted of about two dozen different moves or gestures. Let’s take a stroll through this photo essay, curated exclusively for you, and based on only one location!

Intervention or Invention?

I read somewhere that, as long as the weather has been hot, there has been a fan in existence! And it feels like a profound statement to reiterate how humans looks for ways to make their lives easier.

Almost a hundred years ago, Howard Carter plucked a gold disc from the untouched tomb of Tutankhamun. Found nearby the pharaoh’s body, the gleaming fan – a luminous half-sun – depicted the Boy King steering a chariot. Historical records show that hand fans date back to around 3000 BC, used by the Etruscans, Egyptians, Chinese, and Japanese for cooling. Images of Ramses and Cleopatra often showed the royals in repose as servants fanned them with large, ceremonial fans called flabella. Meanwhile, Japan introduced the “sensu”, or folding fan, a folding fan, around 670 CE, which later evolved to be used as a Tessen or an iron fan by the Samurai.

Fans have always served as more than just a practical means of staying cool in hot, muggy weather. In early civilizations, they served as a ritual and ceremonial object as well as a symbol of sovereignty for senior officials and kings. Common people also use simple hand fans for tasks like fanning a fire or cooling hot meals, a practice still seen in many parts of India.

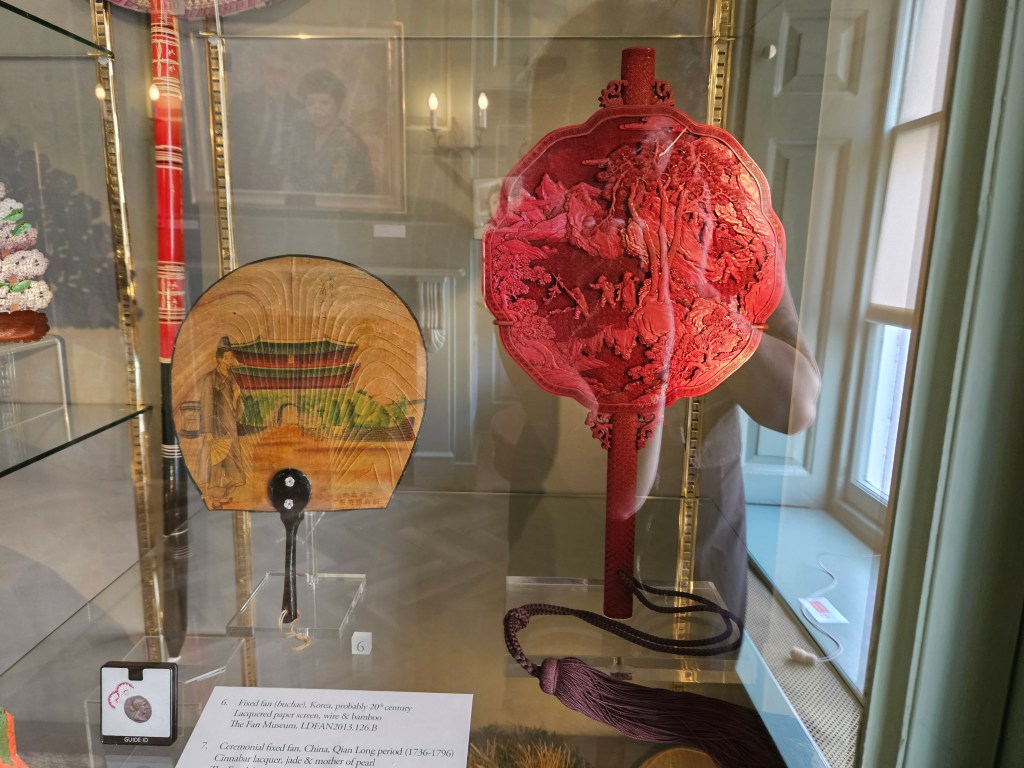

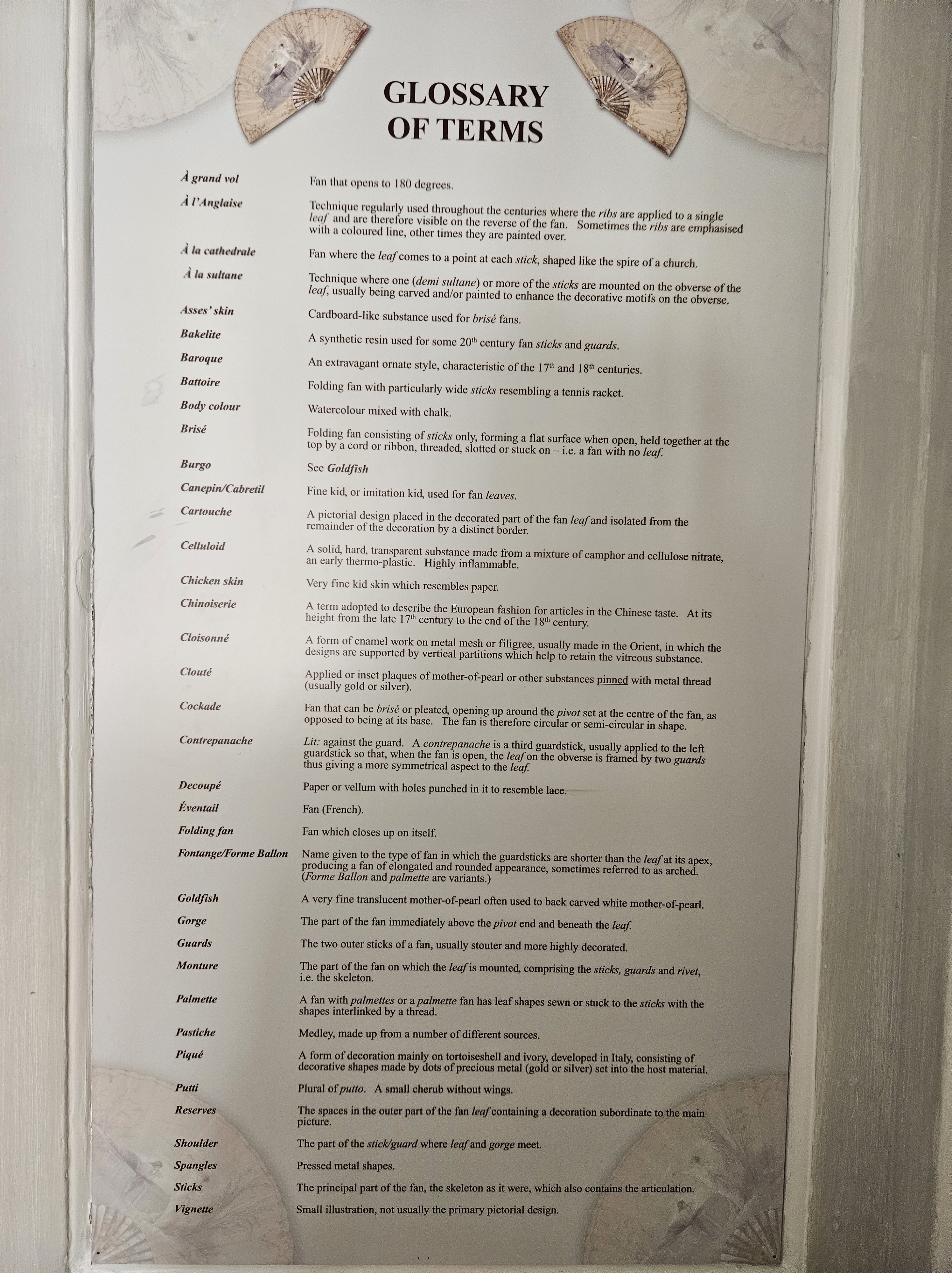

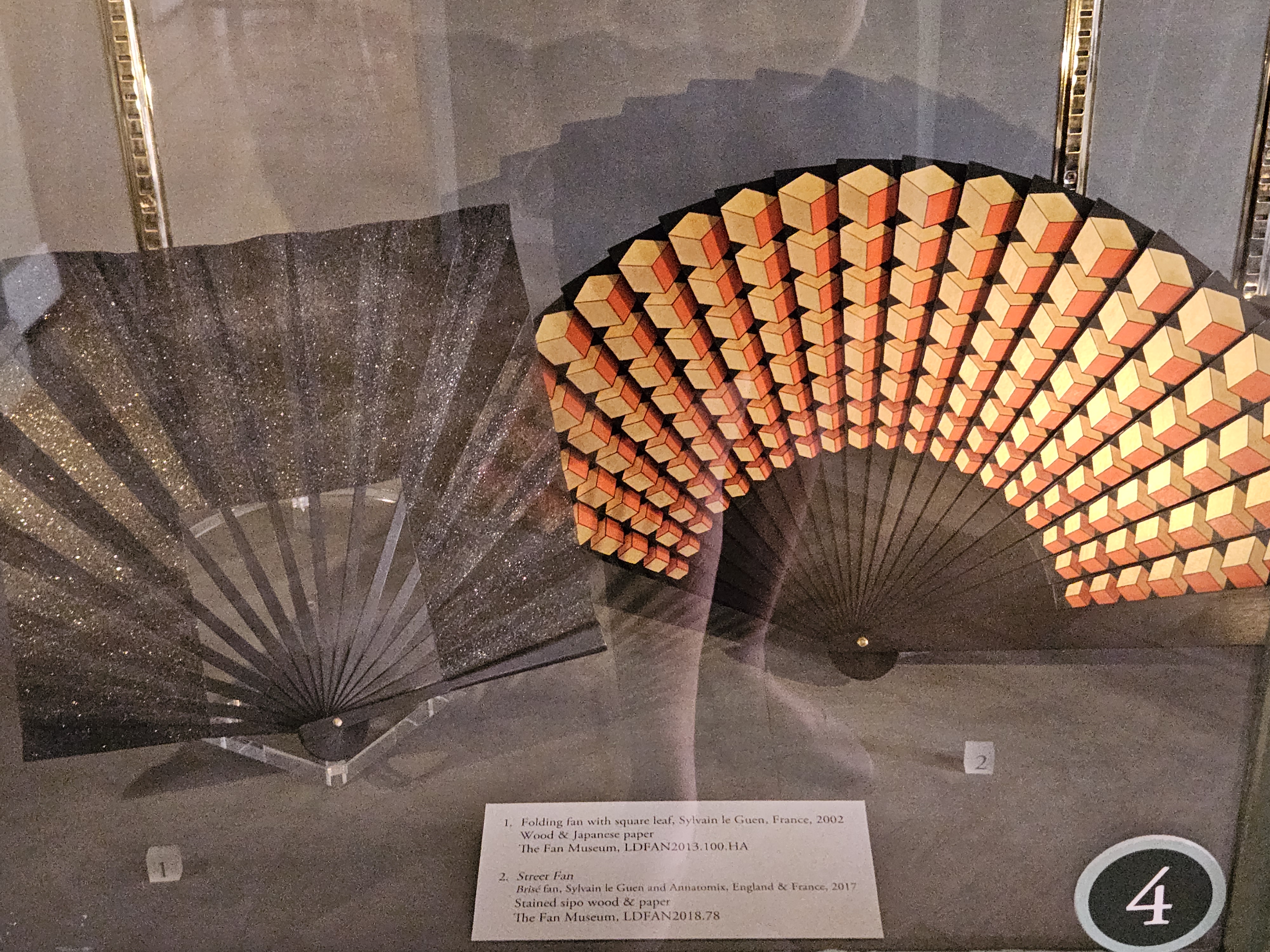

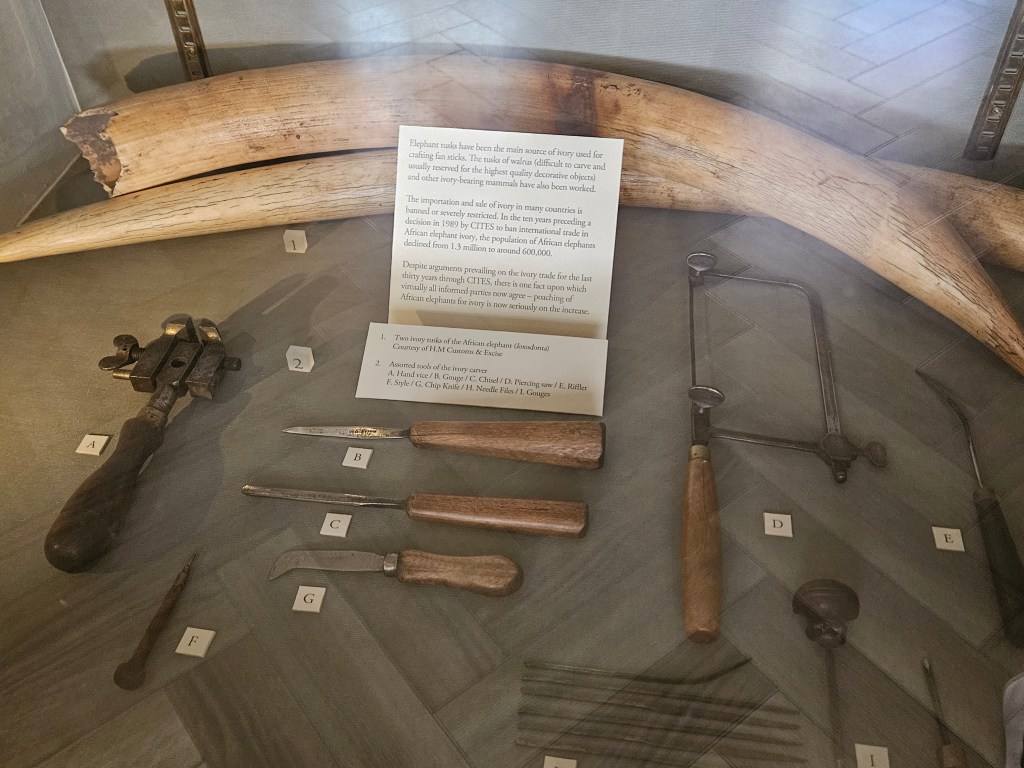

Fan making is a true blend of artistry and craftsmanship, involving a multitude of skilled artisans: weavers, paper makers, carvers, artists, and more. In the West, renowned jewelers like Fabergé crafted fans for the elite, while in the East, artists like Hiroshige of Japan lent their talents to designing fan leaves. For everyday use, cheaper fans were mass-produced with more affordable materials. But fan making is more than just a flick of the wrist—it’s a world of intricate details and specialized terms. Looking at the anatomy and glossary of fan-related terms makes you truly appreciate the artistry behind these fascinating creations.

Global Fans: European Adoption and Evolution

The earliest fans were rigid, made from materials like parchment, metal, and silk. Although the Japanese created the pleated fan around the 12th century, it didn’t reach Europe until the 1500s, brought by merchants and Crusaders traveling the Silk Road. Their popularity initially grew in northern Italy, where Europe’s first fan-making industry emerged.

Over the course of centuries, hand-held fans have appeared in countless portraits of high-born women, where they functioned as female status symbols. Catherine de Medici’s (1519-1589) penchant for fans is evidenced in a number of portraits. Through her marriage to the Duke of Orléans (1519-1559), later King Henry II of France, she introduced the fan to the French court, where it became an indispensable fashion accessory for aristocratic ladies and quickly spread to other European courts. The influencer of first order! A major chunk of her dowry comprised of fans!

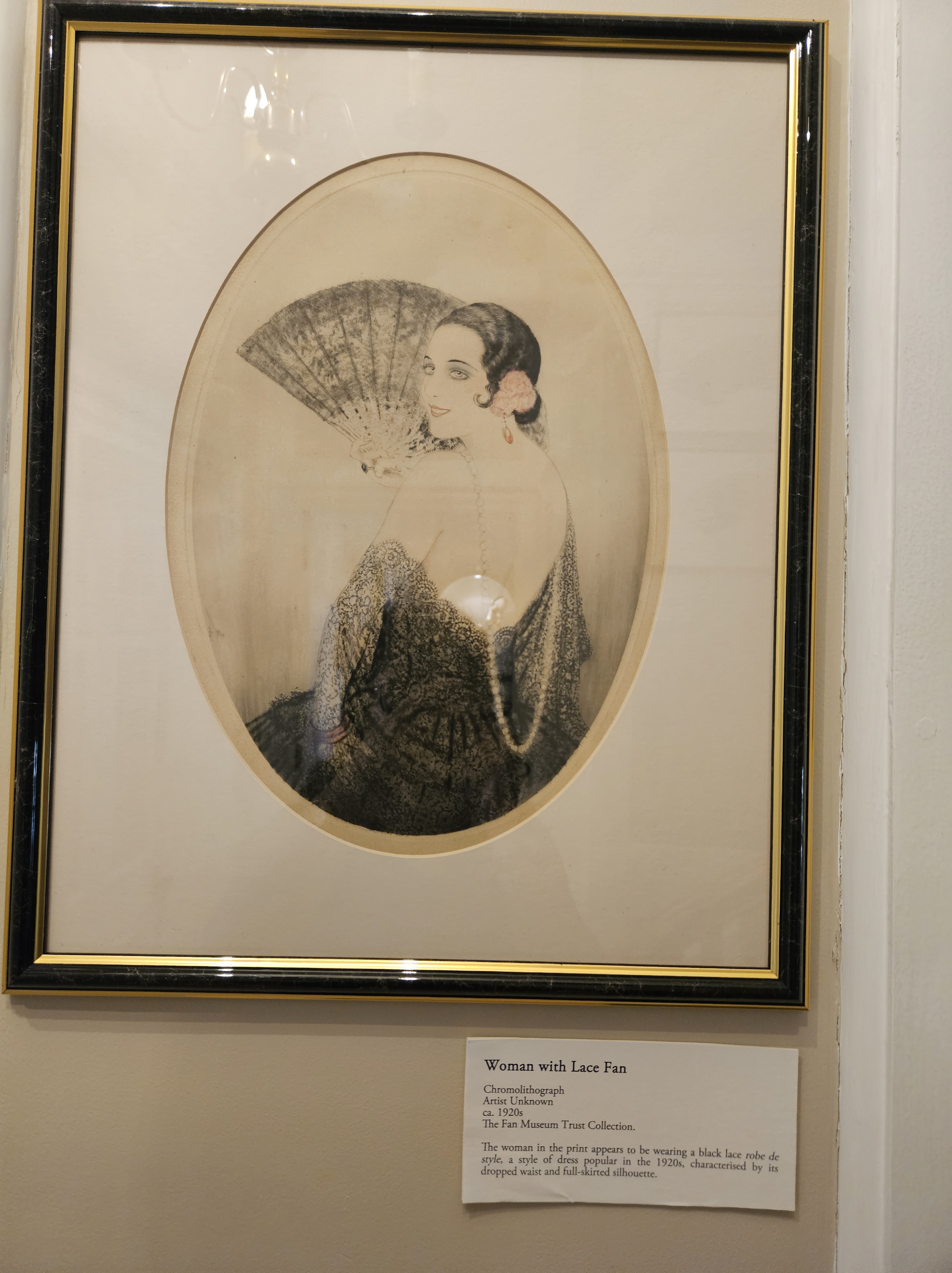

The fan emphasized its holder’s sophistication and sense of style, and signaled a refined way of life that was enjoyed by society’s upper echelons. At the same time, emotions could be concealed behind the fan, as could a goitre, an unsightly sore or bad teeth or maybe something far more saucier. For instance, the infamous Mask Fan in Fan museum is a treasure artifact which was used to conceal their identity while watching a scandolous play or attending a masquerade. The leaf is printed with a series of puzzling vignettes including a woman brandishing a cat-o’-nine-tails with which she vents her fury upon a cowering man. Occupying the central part of the design is a masklike face cut with peepholes.

Language of Fans

Like it says in the world of Bridgerton – it takes more than a charming smile and simple pleasanteries to impress. Japanese women used the Sensu as a flirtation tool or to hide impolite expressions. An open Sensu was used to hide behaviors that were considered socially offensive. It was used to cover the mouth when chewing food or laughing. On the other hand, Japanese men often carried their fans in their hands or tucked into a sash, especially when dressed in ceremonial outfits. The folding fan was a constant companion for a Samurai, particularly during formal events. In the Edo period, a retainer without his fan was considered as incomplete as a Samurai without his Daisho.

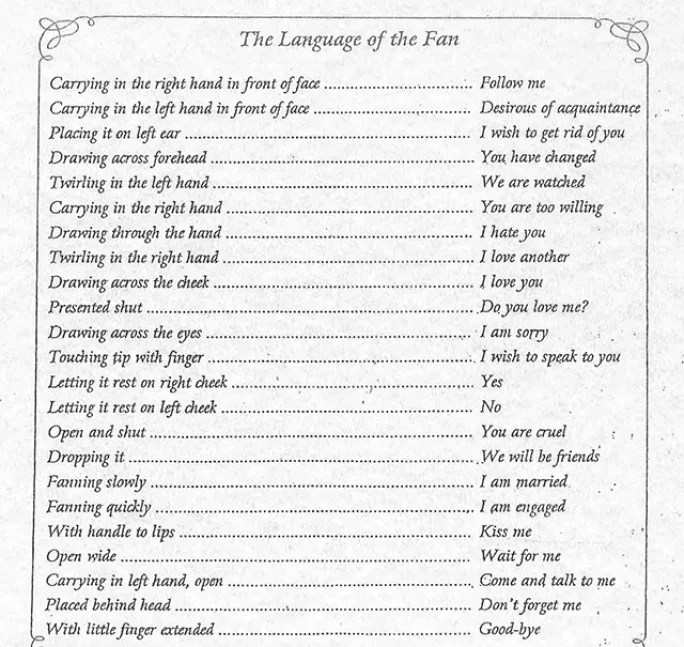

The ‘business of fans’ as such did not exist, but was rather an exaggeration of the fact that a society lady in the 18th century was expected to know how to elegantly handle and hold a fan, allowing observers to differentiate between different social statuses. The first semiofficial gestural fan language was written by a Spanish man known simply as Fenella. Parisian fan-maker Duvelleroy went a step further and published a leaflet documenting “the language of the fan”, broken down by gestures and corresponding explanations. In reality, the less romantic truth is that this so-called fan etiquette was invented in order to boost the sale of fans in the 19th century, after they had fallen out of fashion following the French Revolution. The leaflet proved a great success since Duvelleroy was appointed as fan maker for Queen Victoria.

During the saucy Restoration period, theatre embraced fans to showcase the creative potential of these accessories as props. With the re-legalization of female actors in 1660, for the first time, female actors were allowed to play roles previously performed by young males. They adopted the fan as a stage prop to enhance and exaggerate their their feminine characters and movements. By mastering the art of choreographed fan-handling and fluttering, these actresses could use fans to either reinforce or cleverly subvert the gender stereotypes associated with their roles, adding nuanced expression.

Whether there existed a widespread understanding of those twirls and flicks remains unknown, but nevertheless, the fan achieved a reputation as a tool of romance, coquetry and social politics. French queen Marie Antoinette was reportedly a pro at using her fan to flirt and insult at court. Recalling one meeting with the Queen, the Baroness Oberkirch writes, ‘Her Majesty received me with a smile and a threatening motion of her fan.’

In the 18th and 19th centuries, fans even had different uses. Mourning fans, for example, were made primarily from black ostrich feathers with tortoiseshell handles. They later featured black lace or silk, and dark embellishments. In contrast, wedding fans were usually white or beige, decorated with stones or pearls, and finished in gold or silver. Besides regulating the air temperature, some historians now suggest that one of the main use of fans in the eighteenth century was to protect a woman’s face from the heat of a fire so that she would not develop heat caused ‘coup rose’ or ruddy cheeks. That was because a creamy white complexion was considered more beautiful than a ruddy one. In addition, fans helped to protect a woman’s makeup from being spoiled as most women wore wax-based cosmetics at the time.

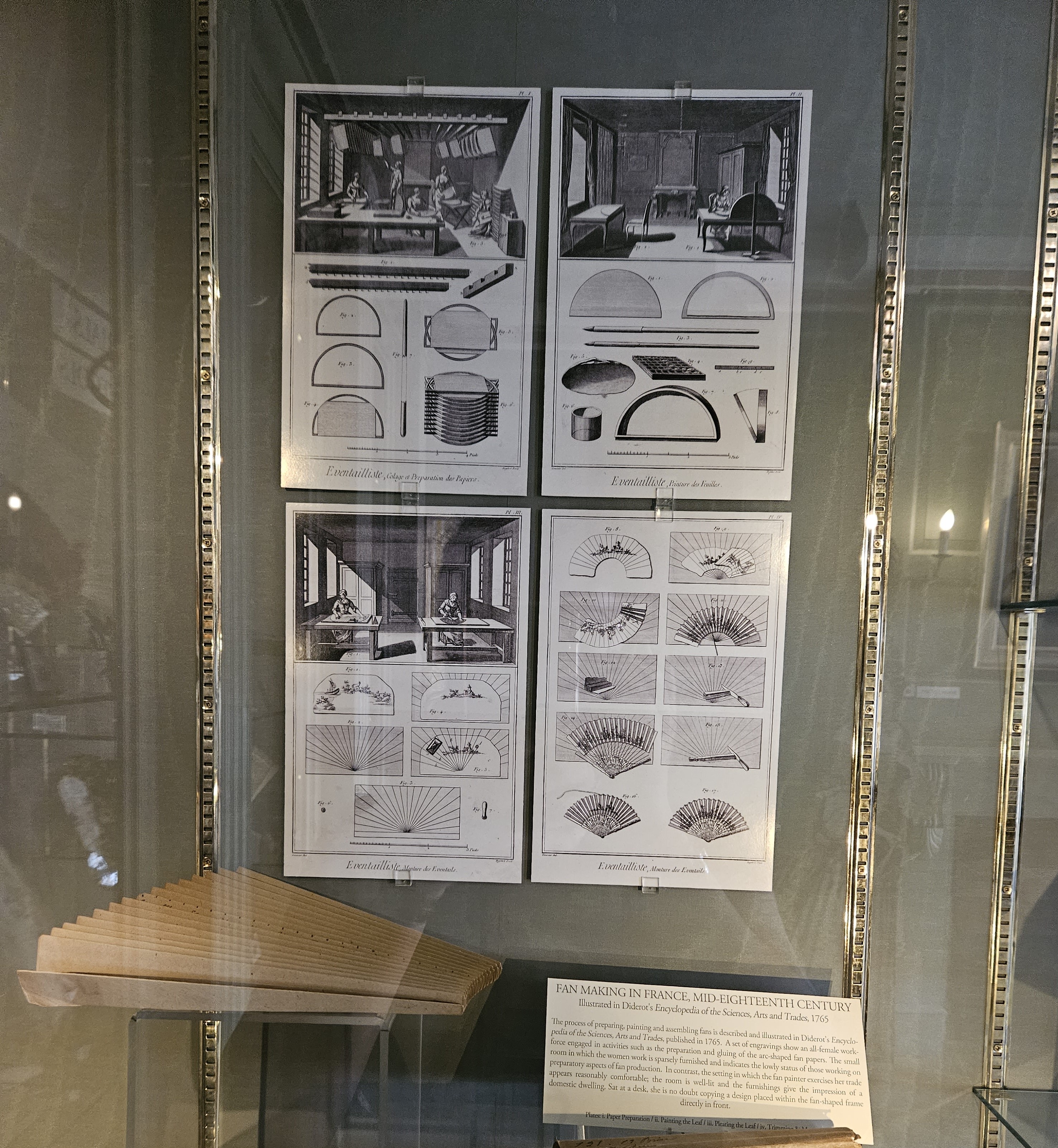

During the 18th century, regarded as the golden age of European fan making, professional fan maker guilds, workshops, and ateliers cropped up across Britain, France, Italy and Spain. In the fan making capitals of Paris and Venice, these workshops employed the leading artists, carvers, engravers and calligraphers who lavishly decorated fans with elegant pierced ivory, exotic wood, and mother-of-pearl montures (mounts); pastoral scenes and romantic scenes took from paintings; gilded classical figures and cherubs; as well as delicate passages replicated from the artworks of renowned painters like Watteau, Fragonard, Boucher and Caravaggio.

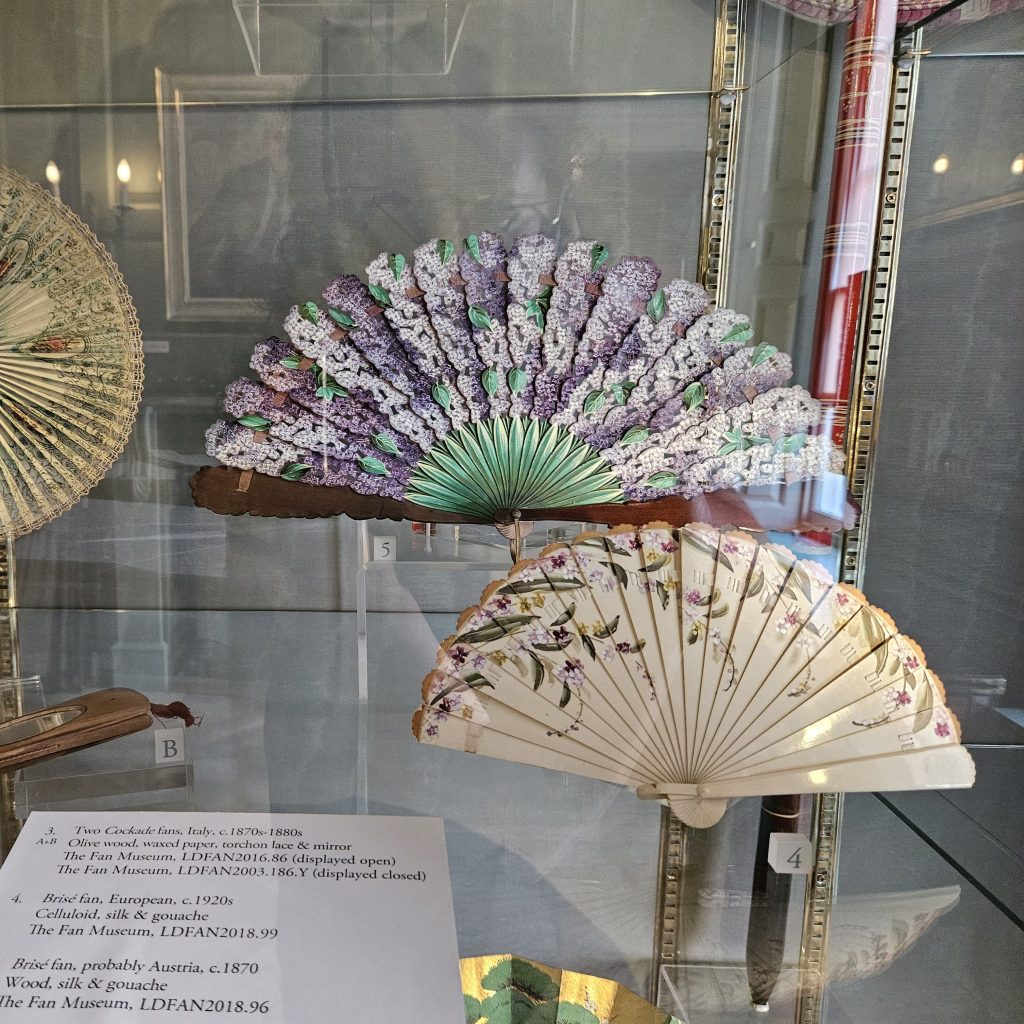

The Impressionist, Art Nouveau, and Art Deco movements highly impacted the design and construction of fans from the 19th to the 20th century . The 19th century boast some of the most lavish fan designs in history and they were usually hand painted, furnishing those in royal positions. In the 20th century, feathered fans became popularized by those in high society and ostrich plums could be see floating through the air at every Moulin Rouge show!

French Royal Fans

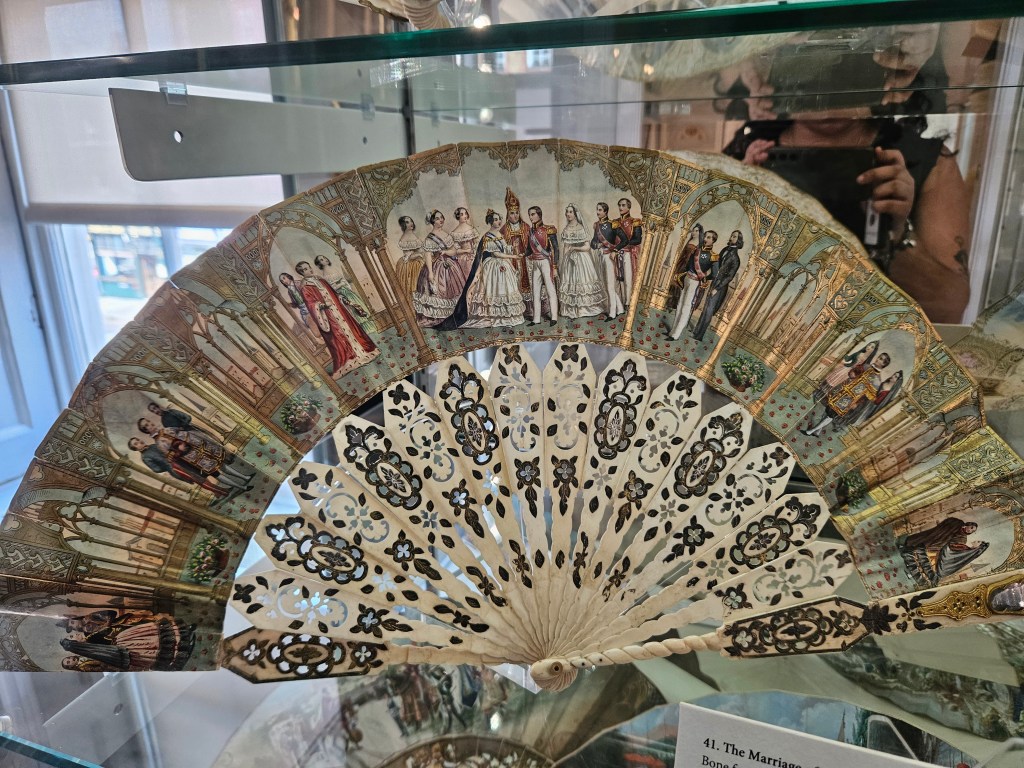

When printed fans became popular, their designs often depicted current events, including monarchical, social, or political happenings. These fans typically featured a central scene flanked by two small vignettes. Meant to be relevant for a short period, they were made from cheap materials, as owners would discard them once the events were no longer fashionable. Fan fashion also played a significant role in traditions like “wedding fans.” These fans, adorned with motifs of historical or mythological marriages, were passed down from mother to daughter on the wedding day, adding a sentimental touch to the occasion.

The first folding fans celebrating French royalty emerged in the early 17th century, often depicting major events at the courts of Louis XIII and Louis XIV at Versailles, or illustrating stories from contemporary newspapers and pamphlets. In fact, during Louis XIV’s reign, France became the fan capital of the world, with French royalty having a particular fondness for extravagant and artistic fans. A prime example is a fan owned by Madam de Pompadour, mistress of Louis XV, which took nine years to create and cost $30,000. This fan featured a paper mount intricately cut to mimic lace and adorned with 10 painted miniatures. (Note: Madam Pompadaour’s fan has not been included in this photo essay)

By the third quarter of the 17th century, Paris and Versailles had become the leading centers of fashion and luxury arts in Europe, a position Paris has maintained intermittently ever since. In 1673, the professional guild Association de Eventaillistes (Fan Makers’ Guild) was chartered under the patronage of Louis XIV. To qualify for membership, fan makers had to serve a 4-year apprenticeship and sometimes produce a masterpiece fan or “chef d’oeuvre” to demonstrate their skills. The entrance fee was 400 Livres.

Many eighteenth-century fans also depicted political events. For instance, there were several fans that showed the storming of the Bastille. Louis Philippe II, Duke of Orléans, also known as Philippe Égalité, was a popular 1700s fan figure known for his vote against Louis XVI’s execution, condemning him to the guillotine. During the French Revolution, fans became canvases for political statements and satire. Depictions of revolutionary uprisings and cheeky anti-monarchy jokes were all the rage among French fan fashionistas. After the French monarchy was overthrown in the Revolution of 1789, fans became a discreet way to display pro-royalist sentiments, hiding coded messages and royalist symbolism in their designs to evade censorship.

Demand for the status symbols of the Ancien Régime, which included the fan, declined dramatically after the French Revolution. Fans, which had once been obligatory accoutrements for high society’s most glamorous boudoirs and balls, suddenly held unpleasant reminders of the decadent aristocracy’s frivolity. As those heavy, sumptuous fabrics fell out of favor, the need to wield fans constantly for keeping one’s cool in stuffy ballrooms and salons diminished. Before long, these intricate works of art were destined to become more objets de vertu adorning fashionable ladies’ dressing rooms rather than necessities clutched in perfectly gloved hands. As the winds of change swept through society, those once highly-coveted fan accessories started losing their elite status symbol cache. With mass production making fans more affordable for the common folk, even middle-class mademoiselles could strut their stuff with a fancy fan in hand.

The 1850s marked a time of prosperity in Europe, particularly in France, where Napoleon III’s rise to power was celebrated with grand balls known as Fête Impériale. At these lavish events, Empress Eugénie and her attendants dazzled in custom-made gowns by Frederick Worth, each carrying magnificent folding fans. Fans continued to be popular throughout the 19th century, with Napoleon Bonaparte serving as a bridge between the 18th and 19th centuries. Fans from this era depicted his journey from a military leader to First Consul and eventually Emperor. They also illustrated his victories, the Peace of Tilsit in 1807, his marriage to Marie-Louise, and his ill-fated Russian campaign, capturing key moments in his storied life.

This random Indian connection took me back to my Mysore trip and reiterated the French connection that Tipu Sultan fostered.

English Royal Fans

In 1685, the Revocation of the Edict of Nantes by Louis XIV, which made Protestant worship illegal in France, resulted in a massive exodus of as many as 200,000 Protestants to neighboring Protestant nations like England, the Dutch Republic, Prussia and Switzerland. This included all the Protestant fanmakers who were members of the Parisian Eventaillistes guild. This dispersal of skilled French craftspeople proved highly influential in the development of luxury arts and industries across Europe in the following centuries. And this is how Fans popularity during the Tudor period came to light

Queen Mary I of England received seven fans as a New Year’s gift from the Spanish court in 1556. A number of portraits in the 1570s during the reign of her sister Queen Elizabeth I show the monarch holding a rigid fan of exotic bird feathers set in a bejeweled handle or monture. It’s claimed that the fashion for fans and luxurious accessories was established at the English court by Elizabeth I, influenced by the tastes of contemporary Italy and France. In the early part of the century, fixed fans made of feathers attached to fancy handles were common. As time went on, folding fans became more popular and eventually replaced fixed fans completely. Interestingly, while royalty and high society favored folding fans, fixed feather fans were often used by the middle class or less affluent.

After a period of austerity during the Puritan rule of Oliver Cromwell in the mid-17th century when ostentatious fashions fell out of style, interest in fans at the English court was revived following the Restoration of the monarchy in 1660 under King Charles II.

The charter establishing the professional London Guild of Fan Makers was awarded in 1709 under Queen Anne, and legislation was introduced to restrict the import of foreign-made fans.

The brisé fan was popular in the 17th and early 18th centuries, but was never as widespread as the folding fan with a painted and pleated leaf. However, in the late 18th and early 19th century smaller fans had come into vogue, perhaps due to the narrower, high-waisted dresses that could no longer accommodate voluminous pockets beneath, where one could tuck a large fan. The smaller fan, often called “opera” size, could have easily slipped into a reticule.

Many eighteenth century fans also showcased music and songs, or even theatre programs. In 1790 E. Ludlow, a fan manufacturer, retailer, and wholesaler, touted what he called the “Country Dance Fan.” Printed on it was information for dances in Bath that contained eighteen of the newest and favorite country dances, along with the music.

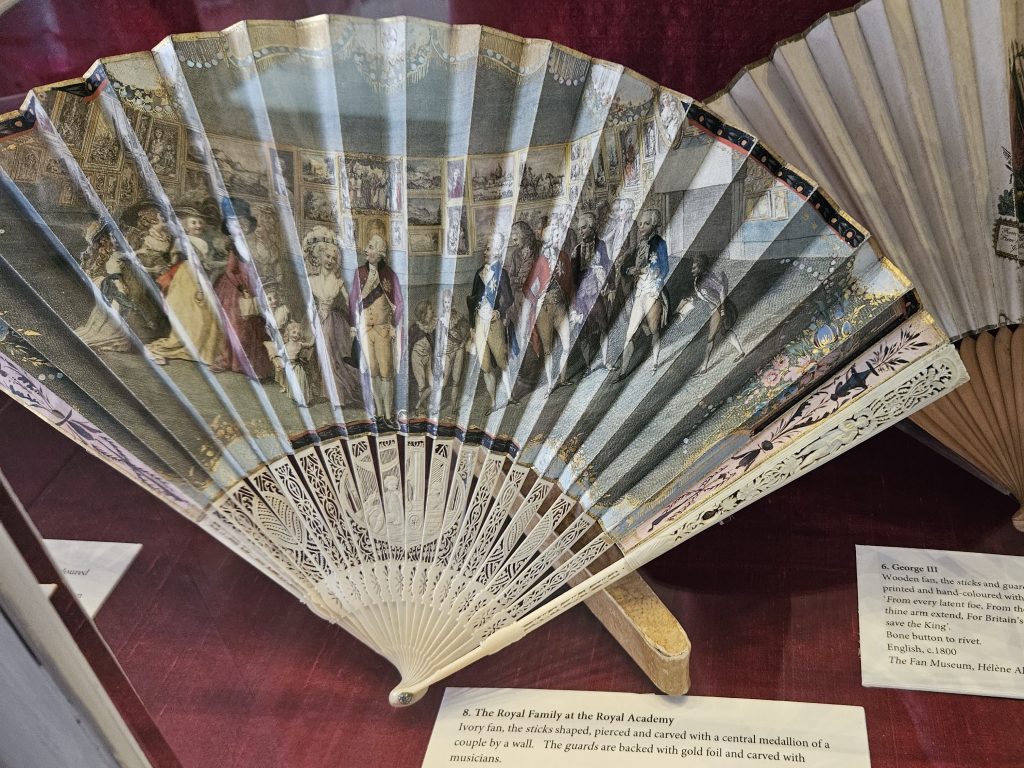

By the early 18th century, the quality of English fan making had risen to rival the French, with English ivory carvings claimed to be equal to Chinese examples. During this period, printed fans could be used for political commentary and to broadcast news like the 1788 depiction of the royal family’s visit to the Royal Academy of Arts in London.

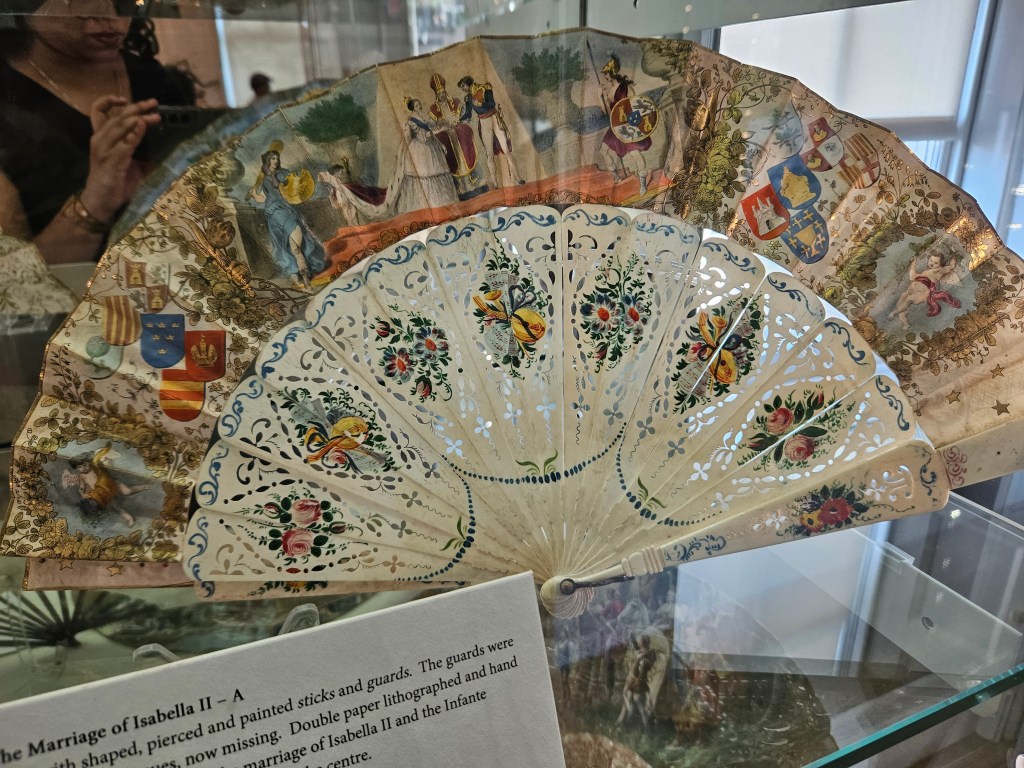

Other European Royal Fans

Hand fans in European culture have both original roots and influences from Asian trade. Since ancient times, Europe has known and crafted hand fans. In Greece, terracotta statues show elegant ladies holding spade-shaped fans, while in Roman circuses, large fans provided fresh air during games. According to Anthony Rich in Le Dictionnaire des Antiquités (1883), Greek and Roman ladies had fans made from lotus leaves, peacock or ostrich feathers, and similar materials. These fans were not folding (brisé) but straight, with long handles, often used by slaves to create a breeze.

The fan craze began in Venice in the 13th century with the flag fan, gaining momentum in the 15th century and becoming a must-have by the 16th century. During the Middle Ages, stylish Italian ladies adored screen fans, which looked like a flag on a stick. These fans were popular with everyone, no matter their social status. Newly married ladies carried delicate white fans, while matrons used more ornate ones. Feathered ones later became popular amongst noble ladies, especially in Venice. This may account for the tradition of including one as part of costumes for the famous Carnivale di Venezia.

By the mid-16th century, folding fans came into fashion, offering more versatility in their designs. Fans featured themes from Classical Mythology, Homeric Epics, the Old and New Testament, historical and political events, and more light-hearted subjects like the lives of the rich and beautiful, the Game of Love, exquisite Burano lace, and reproductions of famous paintings. These fans were not just accessories but a canvas for art and storytelling.

Fast forward to the 1770s, and fans became canvases for classical ruins and Pompeian-style decorations. They often featured dramatic scenes like the eruption of Vesuvius and stunning views of the Bay of Naples, blending elegance with a touch of adventure.

Of the major European nations, Spain embraced fans most enthusiastically into their culture and national traditions. Fans became an integral part of the emotional and sensual flamenco dance that originated among the Roma people in the southern region of Andalusia. An entire choreographed “language of the fan” evolved, where specific gestures and movements conveyed different meanings and intentions between dancers and their audience through a form of body language and flirtation. This is the primarily reason why people often connect the origin of folding fan with Spain.

The folding fan is known in Spanish as an “abanico.” As they gained popularity in Europe, manufacturing increased throughout the Continent, including in Spain, where abanico craftsmanship emerged during the 17th century. Renowned painters were hired to decorate fans for the nobility. In 1797, the Real Fábrica de Abanicos (Royal Fan Factory) was established and produced a wide variety of fans, extending their usage to all social classes, ages, and genders and to occasions ranging from parties to mourning to daily life. Other factories, such as the famous Casa de Dieg, which opened in 1823 in Madrid’s Puerta del Sol and is still in operation today, established Spain as an epicenter for folding fan production.

As Spanish manufacturers thrived, so did the tourism industry. After Napoleon’s failed attempts to capture Spain, the country became a hotspot for adventurers and later for more refined travelers. This boom turned Spanish culture into an export commodity. Washington Irving’s “Tales of the Alhambra,” published in 1832, introduced Spain to the world and was widely circulated. The romanticized depiction of Spain was further popularized by the opera “Carmen,” which premiered in 1875 and portrayed a love triangle involving a Spanish Roma, or gypsy, in the title role. This opera solidified the iconic objects and themes we now associate with Spanish culture.

All the major players are mentioned, but what about the Americans? Fans in America had humbler beginnings. In Boston, women made and mended fans to make a living. Shaker fans were often made from woven straw or paper, quite different from the feathered and jeweled fans of European royalty. By 1866, a significant American fan factory emerged near Quincy, Massachusetts, showcasing Yankee ingenuity. The owner, Hunt, patented a process in 1868 that assembled fan sticks and the fan leaf simultaneously by folding, creasing, and gluing them together under pressure. This innovation gave the Hunt factory a competitive edge until it closed in 1910.

At the end of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th, fans became an ideal advertising tool. The fan had two sides—one side facing the holder and the other the viewer—making it ideal for displaying two messages at once. Advertising fans were used in many capitalist cultures, often even being mass produced. Many of these fans were made with cheap printed paper that could be stripped off and replaced from the ribs (which is where the saying “off with the old, on with the new” comes from) but others were a bit sturdier, such as the catalog fans that showed all of a season’s fashions for sale.

the Fan museum: Ground zero for fan mania

Step into the world of fans at The Fan Museum, one-of-a-kind destination dedicated solely to the rich history, culture, and craftsmanship of fans. Tucked away in the heart of Greenwich, this museum is unlike any other – a small-scale gem, independently run, and officially accredited by Arts Council England.

The unique charm of The Fan Museum is all thanks to its visionary founders, Hélène Alexander MBE and her late husband, ‘Dickie’ A.V Alexander OBE. Together, they dreamt of creating a museum unlike any other, one that transports visitors to bygone eras while warmly embracing them as part of an extended family.

The Fan Museum houses two collections of international renown: the Hélène Alexander Collection of fans, fan leaves & associated materials, and The Fan Museum Trust Collection comprising gifts, bequests, and major acquisitions. Together, the two collections exceed 7,000 objects gathered from across the world and encompassing more than 1,000 years of fan history and culture.

From religion to royalty through to plastics and politics, since first opening to the public in 1991, the Museum’s 85+ temporary exhibitions have covered a breath-taking variety of fan-related topics, often incorporating loans from the Royal Collection and State Hermitage. Typically changing every few months, the upper floor of the museum is devoted to staging temporary exhibitions, carefully curated displays pivot around a central display case which often features period costume and/or objets de vertu relevant to themes explored within the displays.

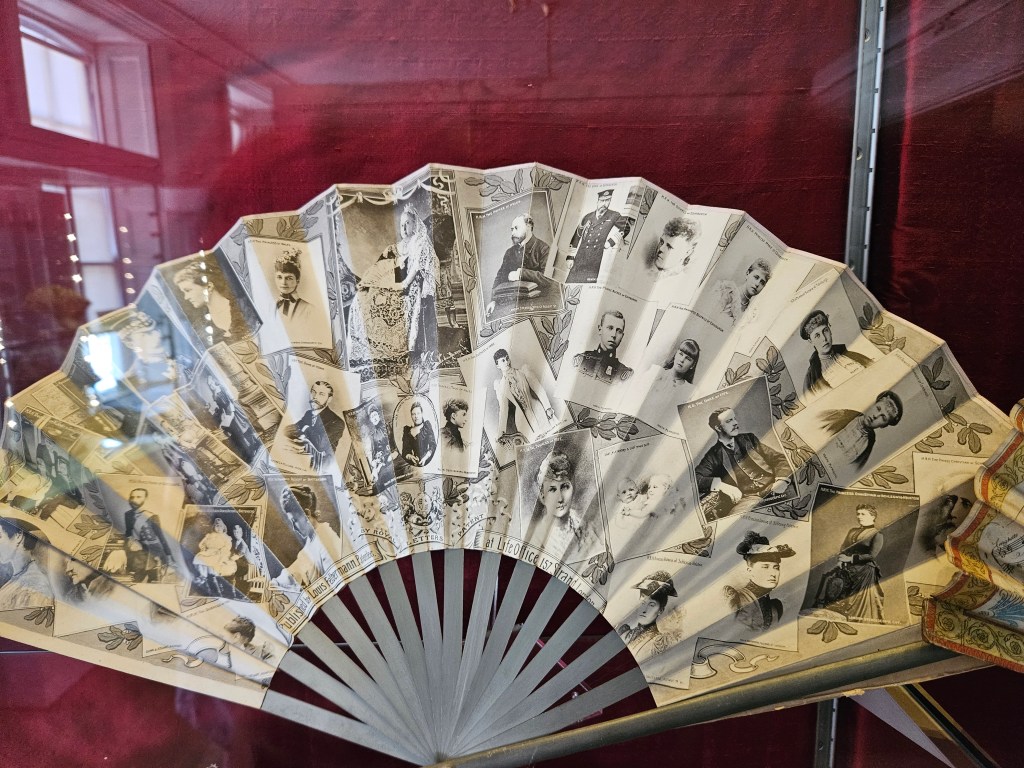

During my visit in June 2023, the theme was centered around Coronations and Celebrations, marking the commemoration of the crowning of King Charles III and the Queen Consort.

Queen Victoria’s Diamond Jubilee in 1897 was a grand celebration that inspired British lace-makers to create special fans for the Queen herself. The Worshipful Company of Fan Makers presented a stunning fan as a gift during their fourth Competitive Exhibition, which was held under Queen Victoria’s patronage. This event marked the first ‘Royal Presentation’ gift from the Fan Makers Company, making it a historic moment.

Fast forward to the late Queen Elizabeth’s Diamond Jubilee, and we see another tribute to royal elegance. The British Royal exhibition showcased a limited edition fan crafted in honor of Queen Elizabeth’s Diamond Jubilee. This masterpiece combined the talents of master fan maker Sylvian Le Guen and renowned artist Charles Summers. The highlight of this fan was Cecil Beaton’s iconic coronation portrait of Queen Elizabeth, adding a crowning touch to this beautiful creation. These fans not only symbolize royal grandeur but also the exquisite craftsmanship of their makers, bridging past and present in a flutter of elegance.

The fact that the temporary collection changes every few months, makes me want to revisit this fascinating place just to check out what new subject I can learn about! Don’t you agree?

Disclaimer: Whichever image has not been credited, has been diligently captured by me at the Fan Museum. As such, it would be much appreciated if any reproduction of the images are duly credited.

Further readings:

The Museum of Kind is a series of unique experiences, as perceived by me. It is not a debate on which is the best of all.

Some additional reading materials that have been referenced in various places throughout this blog:

- Fan museum: online collection

- A little history of fan

- All about Worshipful Company of Fan Makers

- 18th century Fans

- Japanese fan as deadly weapon

- The Mysterious language of Fans

- Traditional Hand fan

- Project Gutenberg ebook history of Fan

Related (and not-so related) Posts:

[…] 05 – Fan Service […]

LikeLike

[…] 05 – Fan Service […]

LikeLike

Definitely on my to-do list when I am next in England! Loved the sheer variety of paintings decorating the fans.

LikeLiked by 1 person

It’s truly beautiful. Even I am planning a revisit to see what’s the temporary collection update will be like!

LikeLiked by 1 person