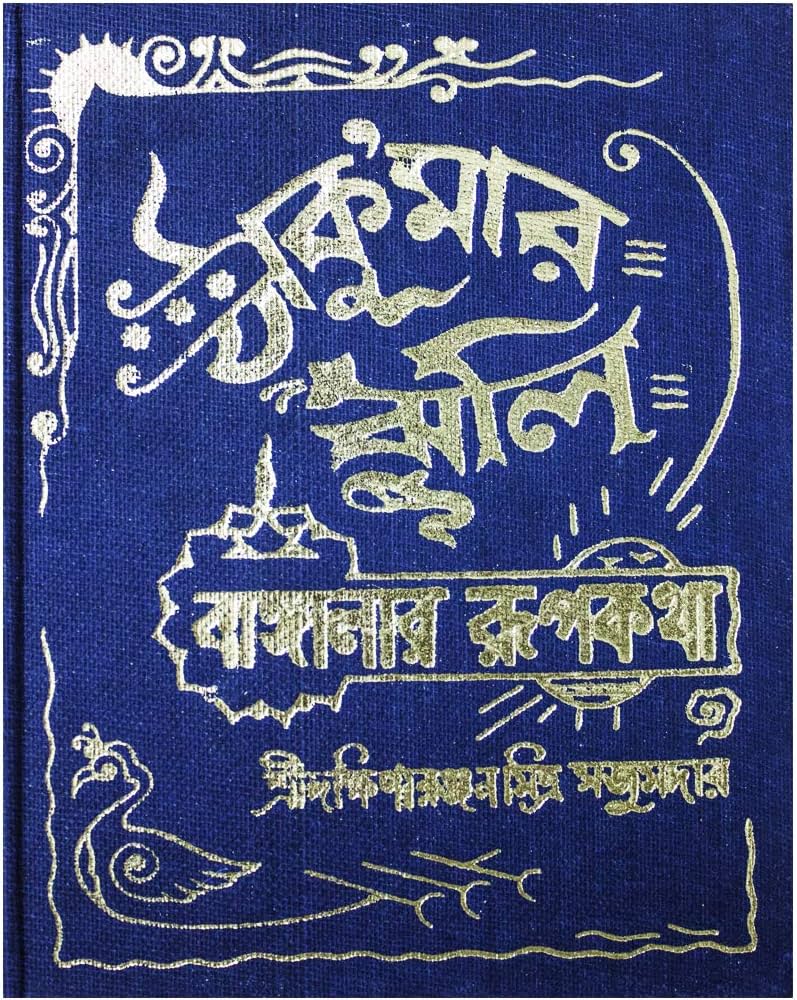

Fairy tales have always held a special place in my heart, conjuring memories of childhood nights spent with eyes wide open, immersed in magical worlds where anything was possible. My memories still paints a picture of the stories told by my parents – while mom used to paint the simple charm of happily-ever-after, dad’s stories were more dark and vivid in their details. One of my prized possession would be a audio cassettes in my native language consisting of Bengali folk tales and fairy tales. I even have the hard copy version of the same, called “Thakurmar Jhuli,” penned by Dakshinaranjan Mitra Majumder which was first published in 1907. The anthology’s introduction was written by none other than Nobel Laureate Rabindranath Tagore. Since its release, this collection has become a cornerstone of Bengali children’s literature, gaining iconic status and becoming a beloved fixture in households across West Bengal and Bangladesh.

I remember going to book fairs and collecting fairy tales. The illustrated book of Princess and the Peas is still something that I vividly remember. It comes as no surprise that I would fall in love with “One Thousand and One Nights” or get enchanted by the rich tapestry of German fairy tales, with their dark forests, whimsical creatures, and lessons etched in folklore. So when the moment presented of visiting a place connecting to these stories, I had to take it up….obviously!!

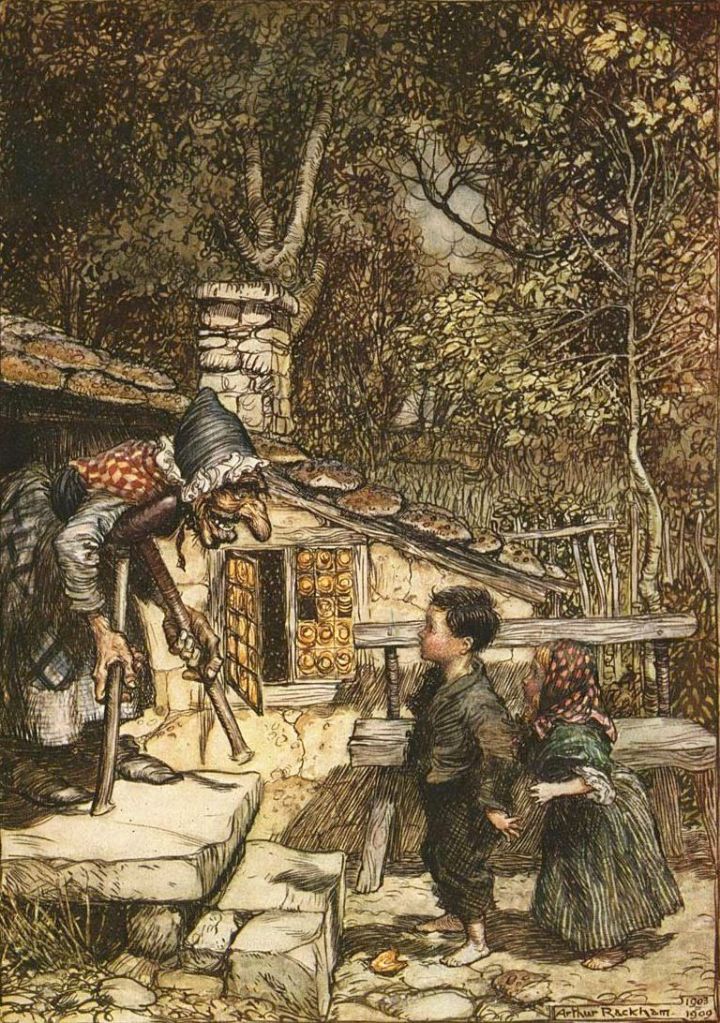

Among the most celebrated storytellers are the Brothers Grimm, whose timeless tales continue to enchant readers around the world, while offering a unique glimpse into the German cultural psyche. Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm collected and published some of the most enduring stories. From the cautionary adventures of “Hansel and Gretel” to the whimsical wonder of “Rapunzel”, or hating the stepmother in “Cinderella”, these stories are rich with German folklore and tradition, and have roots deep in the cultural soil of regions like Bavaria. Even now, they have a unique power to transport us back to a time of wonder and imagination. Though, at 33, there’s a touch of cynicism and mockery associated with these fantasies.

My favorite would be the two buildings that showcase the scenes from Hansel and Gretel (first row of gallery below) and Little Red Riding Hood (second row of gallery below). Both the stories of Little Red Riding Hood and Hansel and Gretel were first published in German as Rottkäppchen by the Grimm Brothers in 1812 in their compilation “Kinder- und Hausmärchen” (Children’s and Household Tales).

November 2023

Nestled in the Bavarian Alps, Oberammergau is a village that seems to have leapt from the pages of a fairy tale. Though the early history of Oberammergau is shrouded in mystery, it is believed that the Celts once inhabited the area. The village’s name, along with its river, the Ammer, likely originates from the Celtic words “Ambrigo” and “Ambara” or “Ampra,” meaning river. The name of the village (as well as that of neighbouring Unterammergau) appears in a well-known German tongue-twister, often sung as a round:

Heut’ kommt der Hans zu mir,

freut sich die Lies.

Ob er aber über Oberammergau

oder aber über Unterammergau

oder aber überhaupt nicht kommt

ist nicht gewiß!Translation:

Today Hans is going to visit me,

Lies is looking forward to it.

But if he arrives via Oberammergau,

or if he arrives via Unterammergau,

or if he arrives at all,

is not certain.(Unterammergau is a village that is situated lower in the Ammer River Valley than Oberammergau. Unter means “below” and ober means “upper.”)

One of the village’s most enchanting features is its Lüftlmalerei frescoes. These vivid murals adorn many of Oberammergau’s buildings, which are a stunning example of trompe-l’œil—an art technique that uses realistic imagery to create the optical illusion of three-dimensionality Lüftlmalerei paintings are more than just decorative art; they are a celebration of Bavarian culture and craftsmanship. The technique required skill and speed, as artists had to apply the paint on wet plaster before it dried—perhaps a nod to the name “Lüftlmalerei,” which some believe is derived from the German word for air, “Luft.” The popularity of Lüftlmalerei soared in the 18th century, as homeowners sought to showcase their wealth and status through elaborate exterior decorations.

One name synonymous with Lüftlmalerei is Franz Seraph Zwinck. Born in Oberammergau, Zwinck became one of the most renowned practitioners of this art form. His works often depicted religious scenes, reflecting the deep spiritual roots of the community. Zwinck lived in a traditional house named Zum Lüftl, which is believed to have inspired the name “Lüftlmalerei.” Locals referred to him as the “Lüftlmaler,” or Lüftl painter, a testament to his influence and the lasting legacy of his art.

While commissioning a Lüftlmalerei today can be quite expensive, the tradition continues to thrive. Modern artists still practice this technique, ensuring that the streets of Oberammergau and other Bavarian villages remain adorned with these exquisite works of art. The frescoes serve as a bridge between the past and present, a reminder of the region’s rich cultural heritage. Walking through Oberammergau, one can’t help but be mesmerized by the Lüftlmalerei. Each painting tells a story, blending history, art, and architecture into a seamless and enchanting whole.

A few captions are written on the walls in old-fashioned script called Gebrochene Schrift.

Oberammergau found favor with Ludwig II of Bavaria, the “fairy tale king.” His influence is still celebrated today, with locals lighting bonfires on the eve of his birthday. Emperor Ludwig the Bavarian ruled the region, establishing the nearby Ettal Monastery and granting Oberammergau residents special privileges, such as transporting goods along the lucrative trade route between Venice and Augsburg. This period of prosperity fostered a thriving community of woodcarvers, whose exquisite works found markets across Europe. These artisans utilized the abundant local wood to create intricate carvings, which they traded across Europe. Pilatushaus in Oberammergau is a beautiful example of frescoes by Franz Seraph Zwinck and offers live demonstrations by wood carvers and artists.

However, the village’s story took a dramatic turn in the early 1630s when the plague swept through the region. Oberammergau initially escaped, but eventually, the Black Death claimed the lives of over 80 villagers. In 1633, the desperate townspeople made a solemn vow to God: if their village was spared further deaths, they would stage a Passion Play every ten years. Miraculously, the plague ceased, and in 1634, Oberammergau’s residents fulfilled their promise by performing the first Passion Play. This promise has been kept for nearly 400 years, transforming the village into a global cultural landmark.

The Passion Play, which depicts the life and death of Jesus, has grown into a grand spectacle involving over 2,000 actors, with every other resident participating in some capacity. Since the first performances and beyond the pandemics, historically, the village has had mixed support, with Duke of Bavaria Maximilian III Joseph trying to ban it in 1770. However, entrepreneur Thomas Cook found it of monetary value and compelled the city to build a 4,400-seat theatre in 1900 to sell foreign audiences on the idea of seeing a five-hour play in a language they didn’t speak, effectively introducing tourism to the region.

The Passion Play has always attracted noted personalities of the time. The delayed 1922 edition was attended by the Italian composer Giacomo Puccini, Herbert Hoover (then US Secretary of Commerce [1921-1929], later US president), and Italian Cardinal Eugenio Giovanni Pacelli (then Apostolic Nuncio to Germany, the future Pope Pius XII). In 1930 the notables included British Prime Minister James Ramsay MacDonald, Queen Elisabeth of Greece, and the American automobile magnate Henry Ford (a known antisemite).

Oberammergau’s history is not without its dark chapters. During the National Socialist era the Passion Play was not immune to Nazi, antisemitic influences. Adolf Hitler, accompanied by a large retinue of Nazi officials, paid a visit to the Passion Play Theater on 13 August 1934, the year of a special 300th anniversary performance. He calls Pontius Pilate the prototype of the Roman who is superior “in race and intelligence” and who seems “like a rock in the midst of the Jewish vermin and swarm.”

Postwar criticism of Oberammergau’s Passion Play centered on its antisemitic portrayal of Jews as responsible for Christ’s death. In 1950, American Jews Arthur Miller and Leonard Bernstein led a petition to cancel the play, but the townspeople performed the 1934 version unchanged. Despite the controversy, the 1950 production drew prominent attendees like US General Dwight D. Eisenhower (later US president), West German Chancellor Konrad Adenauer, and Cardinal Faulhaber. Additionally, the play faced criticism for banning participation by married women and women over 35. This sexist rule was challenged in a lawsuit and eventually abolished by a Munich court in 1990. The 2000 Passion Play, the 40th, attracted an audience of 520,000 for a total of 110 performances. For the first time ever, in another break with tradition, local Muslims were allowed to participate in the 2000 play.

As the Allied forces advanced deeper into Germany, Oberammergau became a refuge for an elite group of German engineers and scientists, setting the stage for a significant episode in the post-war era. In early April 1945, as the Third Reich was crumbling, SS General Hans Kammler ordered a team of 450 “specialists” to be relocated to Oberammergau. This group included some of the most brilliant minds in German rocketry, led by Wernher von Braun, a name that would later become synonymous with space exploration. Von Braun and his team were instrumental in developing the V-2 rocket, a technological marvel of its time and a weapon of terror during the war.

The relocation to Oberammergau was part of a desperate attempt to safeguard these valuable assets from falling into Soviet hands. The idyllic village, known for its peaceful demeanor and artistic traditions, suddenly found itself at the center of a high-stakes game of Cold War espionage. On April 29, 1945, as Allied forces captured Oberammergau, the majority of these engineers were seized. This operation was a crucial moment in what would later be known as Operation Paperclip.

Operation Paperclip was a secret program of the Joint Intelligence Objectives Agency (JIOA) in which more than 1,600 German scientists, engineers, and technicians were taken from Nazi Germany to the United States for government employment, primarily between 1945 and 1959. Wernher von Braun was among the most prominent of these recruits. While the ethical implications of this program remain controversial, it is undeniable that the expertise of these individuals significantly accelerated American advancements in rocketry and space exploration. Von Braun, in particular, played a pivotal role in the American space program. Despite his association with the Nazi regime and the use of forced labor in the production of the V-2 rockets, his scientific prowess was too valuable for the Americans to ignore.

Von Braun was brought to the United States, where he became a key figure in NASA. He was instrumental in the development of the Saturn V rocket, which enabled the Apollo missions to land humans on the moon.

Beyond his contributions to lunar exploration, von Braun was a visionary advocate for human space travel. He famously championed the idea of a manned mission to Mars, laying the groundwork for concepts that continue to inspire space enthusiasts and scientists today. His vision extended far beyond the immediate technological challenges, envisioning a future where humanity could explore and potentially colonize other planets.

In the early 1950s, as Walt Disney was planning the creation of Disneyland, he was inspired by a series of articles on the future of space travel published in Collier’s magazine. These articles featured insights from spaceflight advocates Wernher von Braun and Willy Ley. Recognizing their expertise, Walt hired von Braun and Ley as consultants for his ABC-TV series, Disneyland.

Their collaboration resulted in the groundbreaking episode “Man in Space,” which aired on March 9, 1955, captivating over 40 million viewers with its visionary depiction of rocket launches and an orbiting space station. This episode aired just four months before the Disneyland theme park officially opened.

The success of “Man in Space” led to two sequels: “Man and the Moon,” which aired on December 28, 1955, and “Mars and Beyond,” which aired on December 4, 1957. Von Braun played a crucial role in all three episodes, offering his expertise and contributing to the content.

“Welcome aboard Trans World Airlines’ Rocket to the Moon! In Tomorrowland’s world of 1986 you’ll zoom through space at speeds over 172 thousand miles an hour! Actually experience the “feel” of space travel—see Earth below and Heavens above as you pass space station Terra, coast around the Moon and return! An eight-hour flight in ten thrilling minutes—all without ever leaving the ground.”

PC: Google

Additionally, von Braun’s influence extended to Disneyland itself, where he helped design the iconic TWA Moonliner rocket that became a centerpiece in Tomorrowland, symbolizing humanity’s exciting journey into space.

Walking through the picturesque streets of Oberammergau today, it’s hard to imagine the village’s connection to such monumental historical events. Yet, this blend of cultural heritage and historical significance makes Oberammergau a uniquely compelling destination. My visit to Oberammergau felt like a journey through time and stories, each corner revealing a new facet of its fairy tale charm. Whether it’s the captivating frescoes, the powerful legacy of the Passion Play, or the enchanting alpine backdrop, Oberammergau is a place where history and fantasy intertwine, creating a truly magical experience.

Oberammergau references in popular culture

- Oberammergau’s carved wooden crosses appear in Hugo Hamilton’s novel The Speckled People.

- In the GWAR album Violence Has Arrived, ‘Oberammergau’ is the name of a hell beast that they use to transport themselves around the world. It is mentioned in the songs ‘Anti-Anti-Christ’ and ‘The Song of Words’.

- In Pat Conroy’s novel The Prince of Tides, Savannah Wingo writes a poem which celebrates the “shy Oberammergau of the itinerant barber”; her praise for her grandfather’s tradition of walking around town carrying a 90-pound cross every Good Friday.

- The 1934 film Twentieth Century, starring John Barrymore, mentions the famous passion play.

- In Maud Hart Lovelace’s novel Betsy and the Great World, Betsy visits Oberammergau and meets many of the people involved in the passion play.

- Also, the passion play inspired the Brazilians to create one of the largest outdoor theaters in the world, called New Jerusalem city theater in Pernambuco.

- Jerome K Jerome wrote ‘The Diary of a Pilgrimage’ about his journey to see the Passion Play.

- Mike Ramsdell teaches at the NATO school in his 2005 novel A Train To Potevka.

- A song ‘Oberammergau’ by UK musician Christopher Rye (featuring Chinese rock band Taikonauts) is based on a reference in the book Dark Side of the Moon by Gerard de Groot, to Oberammergau being the destination for the rocket scientists fleeing Nazi Germany at the end of the Second World War, who then helped build the US space programme.

- In the 1976 film Network, at seeing an audition tape, the character Diana Christensen (played by Faye Dunaway) shouts “We don’t want faith healers, evangelists or Oberammergau passion players!”

- German Schlager singer Peter Wackel released a song called “Oberammergau” on the compilation album “Oktoberfest 2008”.

- The 2014 album Eulogy for the Living by the band Ghostrain references Oberammergau in the song Sound at 11.

Recent (and not-so recent) Posts: